Transgender Berkeley

Although transgender rights are now gaining increasing attention in the US, historically transgender people faced much more oppression and flew far beneath the radar. That does not, however, mean that trans people weren’t there, as shown by this cross-section of documents showing the Bay Area’s thriving, if disparate, trans community in the 1970s.

The Bay Area served as a major nexus for the trans community, with Berkeley in particular hosting a wide variety of resources, from the trans-friendly newspaper The Berkeley Barb to the trans support groups at The Pacific Center. However, the trans community in the Bay Area was split along regional lines, with the trans community in Berkeley disproportionately white and middle class, whereas San Francisco and the Tenderloin held more lower-income and transgender people of color—the ones who fought the police the night of the Compton Cafeteria Riot. This disparity extends to surviving documents as well—while we do have documentation of a transgender community whose size and vitality would surprise many modern viewers, as in all areas of history, the stories we have are the stories of those with the resources to write their stories down and preserve them to today.

Trans Folks Find Each Other in Berkeley

The Compton Cafeteria Riots in San Francisco’s Tenderloin sparked a new wave of trans visibility in California. In San Francisco, the first transgender rights organization and peer support group, Conversion Our Goal, formed shortly after. COG was the first of many mental health organizations that arose in the Bay Area, such as Berkeley’s own Pacific Center for Human Growth, founded in 1971 and still alive today offering even more services than it did at its inception. Even in its early years, however, the Pacific Center offered support groups for trans people and gained a renowned reputation. Trans people were building their own spaces to meet each other and assist one another through transition. However, such spaces weren’t the only way trans folks found one another; The Berkeley Barb offered a rich array of articles about trans people and space for trans people to put in personal ads. Through The Barb, trans people could find each other or generate income through sex work, roommate, or employment ads.

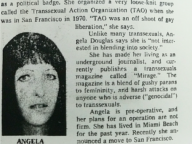

Additionally, The Barb published all sorts of articles about trans people, including Steve Dain, an Emeryville high school teacher who was fired by the school’s superintendent after he transitioned. However, several of these articles, including the piece on Dain, weren’t written by transgender people and reek of an othering, cisgender fascination or gaze. On the other hand, some articles were written by Angela Douglas, a trans woman who moved in and out of Berkeley in the 1970s and founded the Transsexual Action Organization in 1970. Many of her articles attempt to organize and inform trans people as best she can, and she later went on to found Mirage, the first national transsexual magazine, in order to help connect trans people. However, Douglas seemed to be somewhat misguided in her overall politics, with views that adhere to white feminist ideology.

Unlike The Barb, which is not an LGBTQIA specific publication, The Bay Area Reporter, was a magazine with the mission to provide news “for every faction of the gay community.” The Reporter–founded in 1971 and still alive today in a digital format–failed to offer news about trans people, and was written by and catered to members of the gay community. The gay and trans communities remained quite separate during the 1970s, with many spaces, especially lesbian ones, excluding trans people for not having the correct biological traits to be aligned with the space.

Medicalization of the Trans Body

Around the same time as the Compton riots, the Stanford Gender Dysphoria Clinic opened, offering a full-service space for trans healthcare that not only offered services for medical transition, but also therapy and assistance with legal name changes. While Stanford is located in Palo Alto, CA, many trans people from the East Bay and beyond applied to the program. Unfortunately, the program defined only a very specific set of people as actually trans so rejection rates were high, although the program was supposedly esteemed.

The surgeon there, Dr. Donald Laub, was involved in the California case J.D. v Lackner, which decided in favor of Medi-Cal coverage for trans healthcare. The case was an appeal of G.B. v Lackner, in which the plaintiff, G.B., battled health department director Jerome Lackner to receive Medi-Cal coverage for transgender healthcare but lost the case. While Berkeley wasn’t directly involved with the case, Angela Douglas wrote into The Barb calling for the trans community to organize with her rights group called Eon Society in support of J.D.

Unfortunately, insurance coverage wasn’t the only injustice facing trans people. Anti-cross dressing laws were still legal, and trans people frequently were arrested just for being out in public dressed as they felt comfortable. Additionally, the statewide anti-prostitution ordinance was frequently levied against trans people and even though they advertised in The Berkeley Barb, it wasn’t necessarily a safe space. Overall, the trend in the 1970s seemed to be toward defining trans people in exceedingly medical terms that lacked wiggle room, making it seem as though being transgender was a rare “medical condition.”

Feminists, Gay Groups, and Trans People

Part of the reason there was so much medicalization of transgender people came from trans people’s need to defend their legitimacy against a transphobic society. Often, the only way they could have access to medical transition, or even basic respect, was to prove that they were only trans because, medically, they had no other choice—which compounded with a cisgender fascination with trans people’s bodies to create a focus on medicalization.

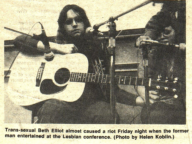

And unfortunately, trans people needed to defend themselves not only to mainstream society, but also to the Left, including the gay rights and feminist movements. Many gay rights groups just forgot about trans people, focusing instead on gay male crossdressers (“transvestites”) and drag performers—ignoring the overlap between cis drag performers and trans ones. While trans people did win some victories, such as admittance to the Gay Activists Alliance in the 1970s, they also faced barriers, such as the supposedly LGBT newspaper The Bay Area Reporter, which published almost exclusively on white, cis gay men (and some lesbians), and the San Francisco chapter of the Daughters of Bilitis, which expelled their vice president, Beth Elliott, after it was discovered that she was a trans woman in late 1972.

In fact, feminist and lesbian groups were a major source of oppression for trans people—especially trans women—and few more publicly than Beth Elliott. After being ousted from the Daughters of Bilitis, she ended up making headlines in feminist and lesbian newspapers across the nation when she was invited to perform at the 1973 West Coast Lesbian Conference. She was viciously protested upon taking the stage, with groups such as the San Francisco Gutter Dykes organizing in advance to pass out fliers condemning and misgendering trans women in the feminist movement. Both newspapers and other speakers at the conference called her an infiltrator, a predator, and a rapist. All of these charges played into common arguments levied against trans people, especially by Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminists, or TERFs, which falsely slandered trans women as predatory “men” out to infiltrate the women’s movement rather than facing their supposed male privilege. These myths and ideologies still exist today, contributing to the dangers trans people face, both through the denial of access to resources, and from concrete threats of violence.

Transsexual Publications

Lacking support in other groups and movements, trans people were often left to found their own spaces—especially in terms of magazines. A wide variety of transsexual publications exist from the 1970s, including Mirage, which was founded by Angela Douglas and was the first national transgender newspaper. Like Mirage, many of these magazines were focused primarily on white trans women. As with Berkeley in general, very few records and publications involving trans people of color remain, suggesting that those who had the ability to publish these newsletters were predominantly white and middle class, leaving them with more access to resources. They were also focused on trans women, who remained the face of both the trans movement, and controversies around it: magazines such as Female Mimics and Drag addressed both the trans feminine community and cisgender male crossdressers.

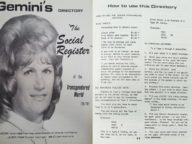

Other publications were actually attached to centers for trans people, such as those affiliated with the Salmacis Society, a South Bay organization that provided support groups, and whose founder set trans women up with access to gender confirmation surgery. Their publications include Gemini Directory, one of the most significant examples we have of trans people creating community: it was a literal directory of not just organizations for trans people, but trans individuals themselves. As a result, all of the contact information listed by the directory was encoded—making it a safe way for trans people to publish their information, but inaccessible to those who didn’t know how to decrypt the magazine.

All of these publications filled a demand not satisfied by the numbers of trans people writing and advertising in Berkeley Barb, the Bay Area’s most trans-friendly newspaper, and one of the most trans friendly in the nation at the time. However, while it did help local trans people find each other and raise awareness of trans issues, given the wide variety of contributors, some trans and some not, the quality and sensitivity of its coverage varied widely. Still, people like Suzy Cooke used the personal ads in the Barb to find each other—proving it did serve a concrete function for people in the trans community.

Conclusion

Out of bits and pieces about transgender history in Berkeley during the 1970s comes a story of push and pull in all different directions. On the one hand, Berkeley offered a newspaper that connected trans people to one another and a no-cost mental health facility. On the other, trans people were forced to carve out space for themselves due to limited acknowledgement in feminist and gay spaces. Trans women faced an enormous amount of violent discrimination especially in Berkeley feminist spaces where Trans Exclusive Radical Feminism reigned supreme.

Furthermore, very little was found on the presence of trans people of color in Berkeley during this era, so it’s probable that the services available for white trans people were less accessible to trans people of color. Even within trans spaces there seems to be some amount of division between assigned female at birth and assigned male at birth people, between transsexuals and transvestites, and also with regards to trans terminology. The debates over terminology likely relate to the increasing medicalization of transgender bodies that occurred in California during the case of J.D. v. Lackner, which ultimately was the biggest legal victory in trans rights during this era.

The Gay Guerrilla Theatre protesting, in 1969, for the right to "wear your gown all year round" (Photo: Bil Paul for the Berkeley Tribe)