Pacific Center

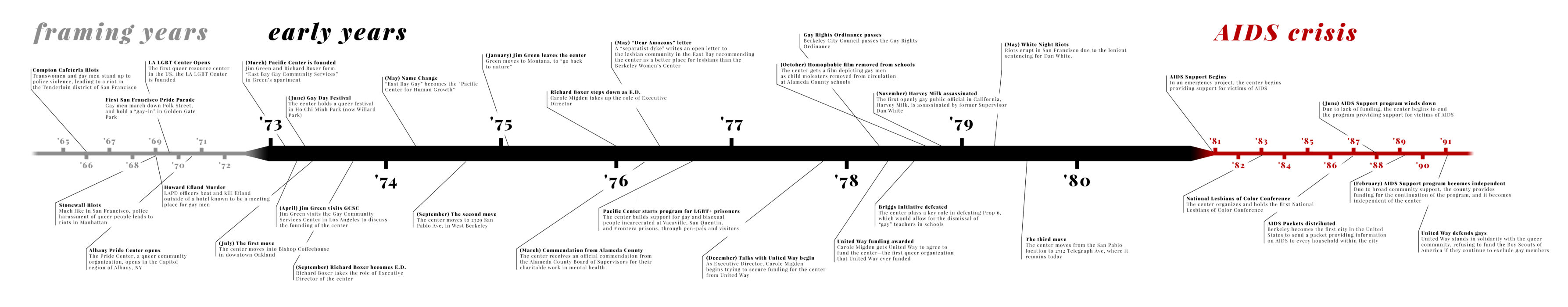

Timeline of Pacific Center, from Compton Cafeteria Riots to AIDS crisis (larger version)

On December 2, 1974, a new type of queer organization — a resource center with a radically inclusive sense of who it might serve — was launched at 2329 San Pablo Avenue, near the corner of Bancroft Avenue in West Berkeley.

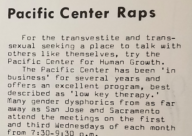

The founders of “Pacific Center” had been the founders, a year earlier, of “East Bay Gay,” and the change of name relayed the broader invitation that they hoped to make to the community. “We plan to be a center for sexual minorities,” said founder Richard Boxer, “and some people in that category, such as heterosexual transvestites, do not label themselves as gay. Our services are used by straight people, by people who refuse to label themselves in sexual/emotional terms, and by those who have a confused identity.” The term ‘gay’, Boxer explained, had left some feeling excluded.

For over four decades, Pacific Center has aimed to put into practice its founding impulse. Rather than offer manifestos, in the mode of other radical groups, it has offered services — counseling, support groups, workshops, speakers programs — while hosting larger events, like dances and concerts, that have helped bring communities together and make new intimacies happen.

Sometimes, as in the case of a dispute over class- and race-based discrimination at a lesbian bar, Pacific Center has served as a mediator in the community. At other times, as in the case of lesbians of color trying to forge a more powerful sense of solidarity, it has served as an organizing space. During the AIDS emergency, Pacific Center rallied a network of volunteers to provide food, counseling, and other forms of care to a community devastated by the health crisis.

The story of Pacific Center has been less told than that of other important queer organizations of its time, partly because it has been oriented more to providing services than to stirring up headlines (though at times it has done so, to good effect), and partly because many of its founding records have been lost. Through interviews with many of those involved in Pacific Center’s earlier days and through a scavenger-like approach to research, we have pieced together the following tale — of an organization that has sought to be ever-sensitive to queer difference while reaching for queer solidarity and unity.

Pacific Center: Origins and Origin Tales

There are several origin tales that have circulated around the founding of Pacific Center, the third-oldest LGBTQ organization in the nation—after Los Angeles’s LGBT Center (1969) and Albany’s Pride Center (1970)—and, according to a founder of the center, two of the main ones are not true.

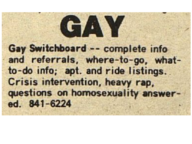

Jim Green — a UC Berkeley alum and co-founder of East Bay Gay, along with Richard Boxer and Gary Fuller — remembers starting East Bay Gay in March 1973 in the living room of his home at the corner of Durant and Telegraph. There, he began hosting a “Gay Switchboard,” which aimed to offer information and referrals for those in need, as well as open conversations for those searching to understand their sexual identity.

Here Green’s story runs counter to the lore that has circulated around the Center: as of May 2018, Pacific Center’s Wikipedia page still suggested that the center’s founders were catalyzed into action by a 1972 gay bashing in an Oakland bar. In an interview, Green suggested that this tale of a gay bashing was in fact just that — a tale, and one that, after being told however long ago, became locked in a decades-long press cycle as the origin story of the center.

Green explained: “While anti-LGBT violence did exist in those days, it was not foremost on our minds as we founded the Pacific Center….There was an obvious need for a source of readily available information for the LGBT community (Switchboard), peer counseling, and what we called ‘rap groups.’ It was a way for people to gain support, make new friends, and enter into community.”

Another origin tale circulates around the motives behind the changing of the center’s name from East Bay Gay to Pacific Center for Human Growth in 1974. Some have suggested that the name change was the result of the IRS refusing to issue nonprofit status — the 501(c)(3) designation — to an organization with “gay” in the name, but Green begs to differ. According to Green, the IRS gave the center its non-profit status without complication.

That said, we might see a larger historical truth that stands behind this particular myth: it was harder to raise funds for non-profits with the word ‘gay’ in their name, as funding agencies and private donors were averse to being associated with a term that still carried an intense stigma.

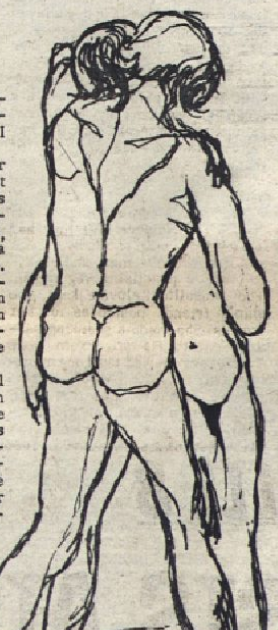

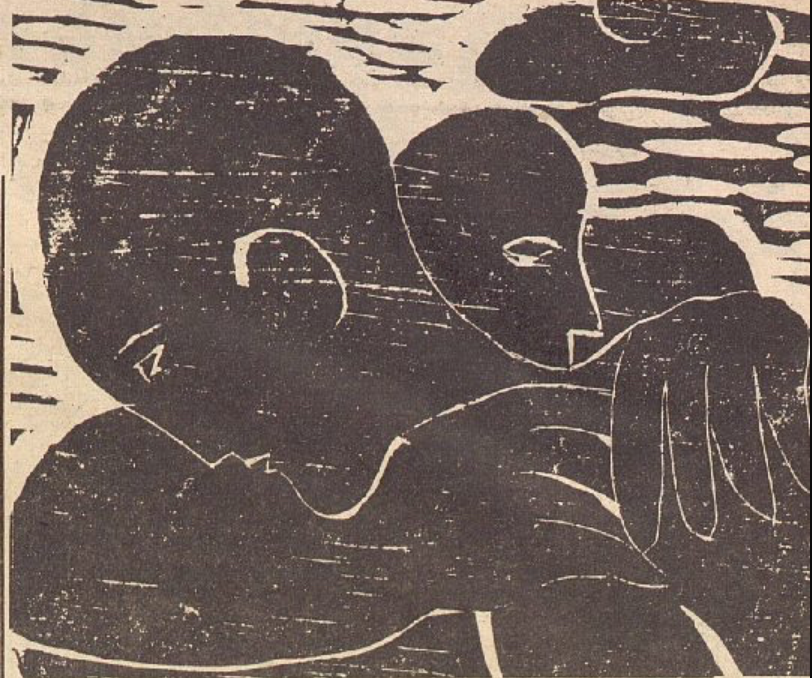

Creating a supportive and loving community (illustration from 1973 Berkeley Barb coverage of East Bay Gay)

Yet, as suggested above, the driving force behind the name change was the founders’ desire to telegraph the broad array of people that the center was already serving, and to advertise the openness of the Center’s continuing invitation to anyone who didn’t fit into the category of “straight,” whether because they identified as gay, bisexual or transvestite, or because they refused sexual labels entirely, or because they were still searching for the label that might fit them.

The openness of that invitation had, from the beginning, produced a groundswell of interest. After starting in Green’s living room in March 1973, East Bay Gay moved its operations in July into a shared office at Bishop’s Coffeehouse in Oakland, where they expanded their services to offer free mental health counseling. Notably, they organized a “counseling collective,” made up of gay therapists and paraprofessionals, so that — at a moment when many therapists regarded being gay as a sickness to be cured — gay people in the East Bay could receive help from gay counselors.

In 1974, the organization officially changed their name to Pacific Center for Human Growth (referred to simply as Pacific Center) and moved into their third home at 2329 San Pablo Avenue in West Berkeley, above Campgrounds Bar. It was here that they continued expanding services and staff, including hosting entertainment events that catered to the LGBTQ community.

In 1978 Pacific Center became the first LGBTQ organization to procure funding from the United Way – a game changer for legitimizing the struggle of sexual minority communities throughout the country. In 1979, the center would make its final move to the 2712 Telegraph Avenue location, their home for the next four decades and counting.

Resource Center for the Community: Rap Groups, Speaker’s Bureau, and More

An important thread in the Pacific Center’s history is that it was always more than a community center—it was a resource center. The distinction here is that the Pacific Center did not strive only to have events and programs focused on building community. The explicit intention of the center was always to provide resources that would directly address needs within the community (hence resource center).

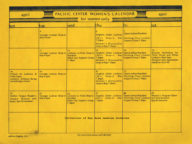

The center offered affordable mental health counseling and—perhaps in a nod to the Berkeley Free Church’s establishment of a “switchboard” for runaways and other young people who arrived in Berkeley in the late-1960s—a “gay switchboard“. One of its most well-attended and enduring programs were its “rap groups” — open groups meant for discussion and interpersonal support, typically focused on a specific demographic or identity. Early rap groups at the center were Men’s Rap, Women’s Rap, Bisexual Rap, and Trans Rap.

As the center grew, so too did the rap groups. Some became significantly larger—the Monday night Gay Men’s group growing to host over 200 attendees by the end of the ’80s—while at the same time the number of groups proliferated, particularly to better include trans/non-binary people, lesbians, younger people, and people of color.

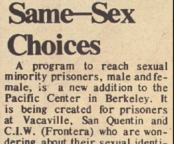

Many other programs grew and expanded alongside the rap groups. In 1976, for example, the Pacific Center began offering information and resources to queer people incarcerated at several California prisons.

A particularly important program that began during this period, though, was the Speaker’s Bureau. The Speaker’s Bureau sent individuals to local secondary schools so that they might speak directly and honestly about queer issues, while providing information about the queer community and other resources the center offered. According to former Executive Director Akaya Windwood, this at the time was “very controversial”: “a lot of the time, [they] were the first… … [openly] queer people that a lot of the young people had ever seen.”

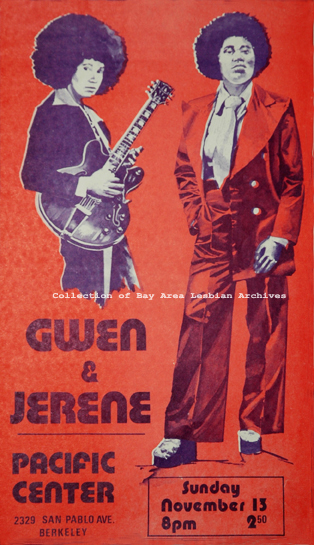

Gwen & Jerene at Pacific Center, Berkeley, c. 1978 (Bay Area Lesbian Archives, courtesy of Lenn Keller)

Another important element of the programs offered by the center was performance. The Pacific Center often hosted music, drama, and other performance-centered events, promoting queer representation and visibility through the arts. The San Pablo Avenue location had access — through the Campgrounds bar — to a stage downstairs, to which they invited musicians, poets, and artists to showcase their work and passion. These events, stretching from the late-’70s through the early-’80s, became an important vehicle for Pacific Center to build a more diverse community, as women of color musicians and other performers made the Center much more than a hub of white, gay male culture.

A Complex Picture of Diversity

Any history of the Pacific Center needs to acknowledge the complex task it set for itself, as a truly open space for sexual differences of all kinds, and the difficulties it faced in addressing deep-seated privileges, exclusions and antagonisms surrounding race, class, gender and sexuality.

According to co-founder Jim Green, the organization was racially quite diverse from the moment of its founding in 1973 until his departure in 1975. Green and fellow co-founder Gary Fuller were members of the Ojibwe (Chippewa) Indian Nation in Minnesota, and took pride in their Native American heritage; Green also recalled the involvement of Bill Beasley and Walter McAlpine, who were among the many African-American activists involved throughout those first years. In its founding mission, East Bay Gay aimed to be a support network and resource center available to all types of sexual and gender minorities, and the organization’s locations—in downtown Oakland at Bishop’s Coffeehouse and on San Pablo Avenue in West Berkeley—suggested how it was making its home in more diverse locations in the East Bay.

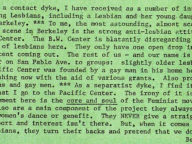

Intentions and impact do not always inevitably align, though, and while anyone may have been welcome there in theory, by the late 70s there were reports that the predominantly white, gay male climate of the center did not foster a welcoming and comfortable experience for people of color, women and trans individuals.

Some locals in the community—such as Lenn Keller, an Oakland-based lesbian of color—sought to change this through their own involvement. In 1977 Keller began working as a Women’s Coordinator at the Pacific Center, where she developed a program for lesbian and bisexual women. Inspired by the stage in their San Pablo location, Keller also began booking lesbian of color performers for events there via the National Network of Lesbian Performers circuit.

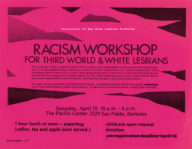

A flyer for a Racism Workshop for Third World and White Lesbians, April 1978 (Bay Area Lesbian Archives, courtesy of Lenn Keller)

Keller maintained a regular volunteer schedule as part of both the crisis switchboard and the Speakers Bureau, and over the next 40 years, she played a tremendous role in expanding groups and workshops within the center to better represent the diversity of the East Bay and address chronic social problems. Among the many projects she initiated were a series of Racism Workshops (launched in 1978), the formation of a Black Gay Support Group, and the creation of a “Third World Survival Manual.”

The story of Akaya Windwood, a former staff member of Pacific Center, offers another glimpse into how issues of discrimination continued to play out within the infrastructure of the Pacific Center, even as the center’s clientele and staff became more diverse. After becoming radicalized during her time attending UC Berkeley, Windwood joined the center in 1991. Beginning as Director of the Speakers Bureau, she was very quickly offered a promotion to Executive Director — the first time that the center had had a woman of color at its head.

In her new role, Windwood soon recognized an imbalanced allocation of use of the center between the Monday Night Gay’s Mens group that served predominantly white, gay men and the many other clients groups being served. After she set about to redistribute use of space in a more equitable manner, the same white member of the board of directors who had nominated Windwood as director began claiming that she was racist and discriminating against the Monday night group, and petitioned for her removal. In response, people of color began picketing during the Monday night group; quickly, things became tense.

Looking back on the controversy, Windwood offered that she did not see it as the result of “a racial divide.” She parsed it in a way that resonates with the history of the nation as a whole: there was “one group of people falling on the side of equity and fairness, and the other on a side fearful of losing privileges.” The situation dragged on for some time until Windwood left the Pacific Center, inspired to develop a consulting firm centered on race, class and discrimination within the non-profit sector.

While the Pacific Center has certainly diversified dynamically over the past several decades, now offering programs and rap groups for a vast range of intersectional identities, it’s important to recognize the figures who came before and laid the foundation for this to be possible. It is also worth noting, though, that there is and always will be more work that needs to be done—a sentiment that seems to be shared by the current Executive Director, Leslie Ewing, as she looks to shape the Pacific Center’s future.

The Fight for Funding: Finding Financial Allies to Support Gay Services

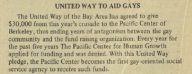

From the very beginnings of East Bay Gay in 1973, there was a clear need for funding to expand highly sought-after services for the local LGBTQ community. The organization initially received some funding through the UC Berkeley Student Government, but Pacific Center co-founder Richard Boxer recognized early on that it would need other sources of support: he began writing grant applications for submission to local and federal government and various charitable fundraising organizations, including United Way Bay Area. The United Way was one of the largest and most well-known fundraising organizations—meaning that funding from them would lend legitimacy to the struggle for sexual minorities as a marginalized and at-risk community. For the following five years, despite obtaining funding from the San Francisco Foundation, Alameda County and other local organizations, Pacific Center would continue to be rejected by the United Way in the final rounds of review.

In December 1977 Carole Migden took over as Executive Director of the Center, becoming its first female director and initiating a change of approach. After conferring with Richard Boxer over the upcoming 1977-78 United Way application, Migden included a letter with their application that called out the discrimination the center had faced over the course of five years of grant reviews; strikingly, Migden sent copies of this letter to both press and political figures, including the mayor of San Francisco. While the letter was not well received by everyone who viewed it, it did change the equilibrium of the Center’s relationship with United Way. In 1978, the Pacific Center became the first LGBTQ organization in the nation to be funded by the United Way — a landmark achievement.

In 1992, the United Way of the Bay Area announced that it would no longer support the Boy Scouts of America because of its longstanding policy banning queer scouts and troop leaders — a historical turnaround whose roots lie, in part, in Pacific Center’s self-advocacy within the organization.

A Lifeline During the AIDS Epidemic

While HIV had been circulating in the United States for years, in 1981, it began to spread seriously in the Bay Area—a phenomenon that came to be known as the AIDS epidemic. By the end of the year, 270 gay men had reported cases of severe immune deficiency due to HIV/AIDS, and 121 of them had died. With the burden of the disease disproportionately affecting the gay population of the Bay Area, it became clear that the queer community needed to come together to support victims of HIV/AIDS.

In 1981, the Pacific Center stepped up, launching an (originally short-term) emergency program offering mental health assistance to victims. According to current executive director Leslie Ewing, the Pacific Center’s relatively small size allowed it to act quickly and decisively, providing desperately needed support for the community before many other organizations were able to transition to serve this need. As the crisis grew, so too did the program, and the Pacific Center’s AIDS Project divided into two parts: the AIDS Client Services Department, offering free counseling and training to victims and their families and friends, and the AIDS Education Department, providing informational outreach to the community at large.

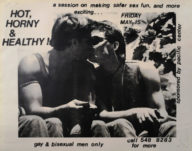

“Hot, horny & healthy!”: flyer for Safe Sex workshop during the AIDS Crisis, held at Pacific Center

While much of the public health infrastructure in America, and even the Bay Area, took an abstinence-based medical approach at first to the control on the AIDS crisis, Pacific Center took a leading role in the creation of a community-based approach, advocating for safe-sex and public awareness. This tactic proved significantly more effective than abstinence tactics and garnered significantly more support within the queer community. In 1987, with the support of the Pacific Center, Berkeley became the first city in the United States to distribute informational packets on AIDS to every home in the city.

Through the 1980s, Pacific Center continued to play a pivotal role in community support during the AIDS crisis. In 1988, when severe monetary troubles forced the center to begin to close operations on the AIDS Project, news of the closure circulated through the East Bay, and the community rallied in support of the center: by 1989, it was able to get enough funding for the AIDS Project to continue. In this period, the AIDS project became independent of the Pacific Center, allowing the center to transition back to mounting its larger array of programs, which had suffered for funding through the 1980s, given the pull of resources to the AIDS Project.

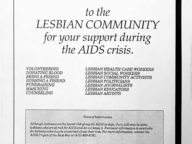

A critical part of Pacific Center’s response to the AIDS epidemic was the powerful and expansive sense of solidarity that it generated and put to use. Despite being the group statistically at the least risk of contracting HIV, the lesbian community rallied dramatically to provide support for the gay men of the area. While through much of its history the Pacific Center had struggled with diversity and equity within the queer community, during the AIDS crisis the community came together in an unprecedented fashion—a phenomenon that both Lenn Keller and Leslie Ewing noted. The AIDS Project was an undertaking born of queer unity, and its success is a reminder of the power of endeavors that bring a larger, diverse community into coalescence.

— Dylan Burgoon and Sarah Sexton

Acknowledgements

We would like to extend a warm thank you to Leslie Ewing and Anne Mitchell of Pacific Center, Lenn Keller and the Bay Area Lesbian Archives, Akaya Windwood, Liam O’Donoghue, Cathy Cade, Stefano Gonzalez and all the other countless individuals who helped us pull together these documents and personal histories of Pacific Center. We couldn’t have realized this project without you.

We especially encourage people to support the Bay Area Lesbian Archives, a crucial organization that is pulling together the larger history told in this project.

Illustration from the 1974 opening of Pacific Center (Berkeley Barb)

A profile of Pacific Center, from Bay Area Focus (2014)