The Flatlands’ War on Poverty

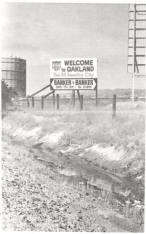

“Welcome to Oakland, the all-American city; welcome to Oakland, the 'city of pain'.”

— The first lines of The Flatlands' first issue

In the spring of 1966, a new newspaper, driven by the spirit of community organizing, sprang up in in Oakland. Its barebones layout, stark black-and-white photography and hard-charging editorial line placed it firmly in the American tradition of no-nonsense, muck-raking journalism.

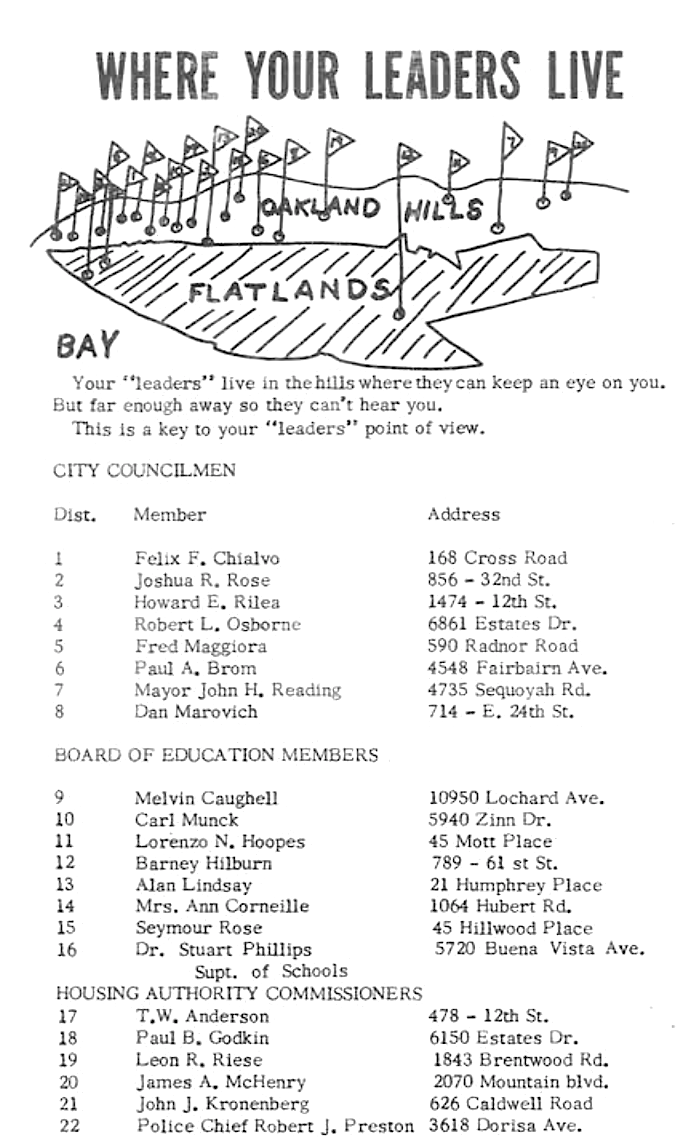

Tellingly, the inaugural issue called out Oakland’s municipal establishment by printing the names and addresses of each member of the city council, Board of Education, and Housing Authority. An accompanying cartoon mapped their distribution within the city and revealed the spatial segregation that structured Oakland — how its elite, by and large, inhabited tony suburban neighborhoods in the hills. To signify an alliance with the Oakland’s working-class neighborhoods, overlooked literally and figuratively by those in the hills, the paper called itself The Flatlands.

Throughout two years of occasionally irregular publication, The Flatlands chronicled in detail the indignities and injustices inflicted upon the city’s most vulnerable citizens, championing their interests and fighting tirelessly to center their stories.

The acerbic photograph that decorated the cover of The Flatlands‘ first issue: Oakland was an “all-American city”, run by bankers — and was uninhabitable as a result (Howard Harawitz)

At the time of the paper’s founding, Oakland was experiencing the economic and social turmoil common among mid-sized American cities. White residents and businesses were fleeing into surrounding communities like San Leandro, Hayward, and Castro Valley for their promise of lower taxes, newer industrial infrastructure, and the allure of suburban living. Unable to reverse a shrinking tax base and reluctant to address growing social problems, Oakland’s conservative and overwhelmingly white political leadership came under criticism as poverty and unemployment increased and center-city schools declined for lack of investment. President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty brought millions of dollars to the city in anti-poverty grants, but its intended beneficiaries resented the federal government’s paternalism. Activists called for the funding program to honor its promise of “maximum feasible participation of the poor.” To those fighting such struggles, The Flatlands pledged its full support.

The Flatlands exemplified the spirit of an era marked by radical critique of the status quo. Civil rights activists, block club organizers, seminarians and clergymen, Berkeley students and anti-poverty officials all published in its pages. Above all else, The Flatlands sought to promote the needs and aspirations of the city’s marginalized residents. Summarizing the editors’ faith in the power of blunt truth and direct action to achieve social and political change, the paper’s motto, “Tell it like it is, and do what is needed,” appeared above the fold on every issue.

The Flatlands‘ banner

The People of The Flatlands

The birth of The Flatlands illuminates the network linking university and community activists. An initial community-organizing grant of $100,000, awarded to editor Alexandra Close and photographer Lynn Phipps, both UC Berkeley graduates, through the efforts of UC Berkeley Extension official Lew Harris, financed much of the newspaper’s first year of operation. Close would write most of the paper’s unsigned articles at first; photographs by Phipps joined those of contributors like Howard Harawitz and Thomas W. Tenney.

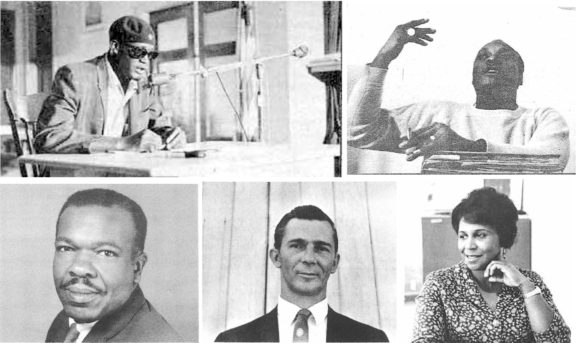

In bringing together the paper’s editorial board, Close drew from a pool of respected Oakland activists, who ranged in age from their twenties to their fifties: West Oakland’s brash Curtis Lee Baker; former Oakland PTA head and East Oakland community organizer Agnes Woods; neighborhood activist Ralph Williams; Mark Comfort, a veteran of the Bay Area’s anti-employment discrimination campaign; Bill and Pauline Goetz, neighborhood association organizers; and John George, a local civil rights attorney with political ambitions.

The people of The Flatlands (clockwise from top): Curtis Baker, Mark Comfort, Agnes Woods, Bill Goetz and William Lowe

Together, the editorial board helped to solicit contributions from figures such as future Oakland Post publisher Paul Cobb and former Oakland Committee on Full Opportunity member Electra Price. Other key contributors to The Flatlands included Richard York, a seminarian and leader of the Peralta Improvement League, and Dr. Jack D. Forbes, an anthropologist who wrote dispatches on California’s black and native history.

Around the time of the paper’s first anniversary, the editorial board underwent a shakeup with the departures of Baker and Williams; by this point, too, Close had left because The Flatlands could not afford to pay a full-time editor. Gerry Leo, an Oakland native and the paper’s sole Chinese-American staffer, was elected president. Agnes Woods served as vice president, and Bay Area movement veteran Bill Lowe, formerly a leader of Bay Area AFL-CIO’s political arm, became treasurer.

Democratizing the War on Poverty: Putting It in the Hands of the Poor

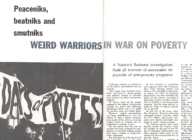

Long-standing disagreements among Oakland’s civil rights leaders came to the surface in a struggle over the distribution of federal money made available through War on Poverty grants. The funds flowed through the Oakland Economic Development Council (OEDC), an appointed city board that exerted tremendous control over the allocation and distribution of resources. OEDC membership favored civic-minded business, political and religious leaders who, like other Oakland elites, lived in the hills, a world away from the neighborhoods desperately in need of anti-poverty funds. Ensuring that those communities had a voice in the OEDC was the goal of an initial social justice campaign by contributors to The Flatlands.

In pressing its case, the newspaper broke with journalistic conventions regarding reporter objectivity. Some contributors, like Agnes Woods, had entry-level positions as social workers within the anti-poverty program; others, like Bill Lowe and Ralph Williams, served on the Target Area Advisory Committees (TAAC) which reported neighborhoods slated for funding but lacked OEDC voting power. Coverage in The Flatlands concerning the conflict between poverty workers and the OEDC was highly partisan. An article on a demonstration at a city council meeting could be followed the following week with an editorial on the subject written by one of the demonstrators. The newspaper’s key editorial figures also took part in the battle, heavily coloring coverage of the conflict. At the same time, The Flatlands aimed to allow the poor to tell their own story; its staff sometimes operated as oral historians as much as journalists, opening their pages so that the poor could speak about their own experience in their own words.

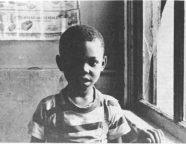

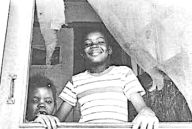

Featured: The Flatlands often depicted the everyday lives of those in public housing (Lynn Phipps)

The campaign to enforce the War on Poverty’s commitment to maximum feasible participation of the poor proved one of The Flatlands’ great successes. Its “51% participation” proposal required that over half the OEDC membership reside in one of the program’s four target neighborhoods of North Oakland, West Oakland, Fruitvale and East Oakland. By sparking a public discussion about class segregation and community self-determination and by winning a victory on the 51% issue, the campaign provided a template for activists lobbying for local control in organizations and initiatives ranging from the Corporation for the Poor to the Model Cities program.

The Battle for Community Control of the Police

The Flatlands also regularly took on the Oakland Police Department, which in the mid-1960s was almost entirely white (having recruited heavily from Southern cities) and was known as an especially brutal and lawless force. The newspaper adopted as its mission the creation of a civilian review board to curb police abuse of power. The issue was personal for contributors like Mark Comfort, who traced his political awakening to his youthful interactions with Oakland police. The newspaper’s response strategies ranged from analysis and first-hand coverage of police brutality and its community impact, as in the September 1966 riots at Hunters Point in San Francisco, to forms of direct action that turned reporters into agents of change.

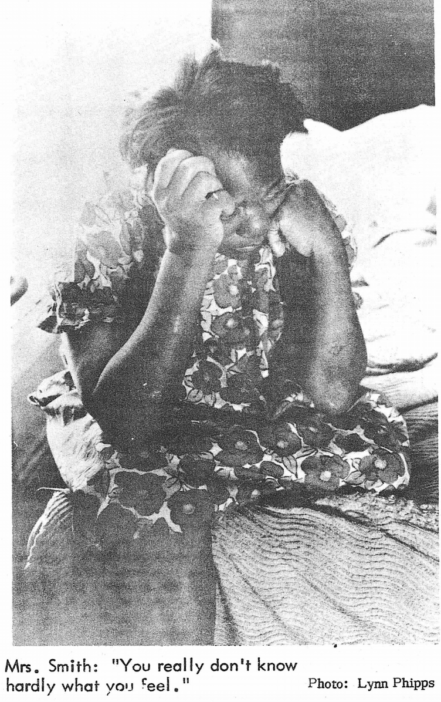

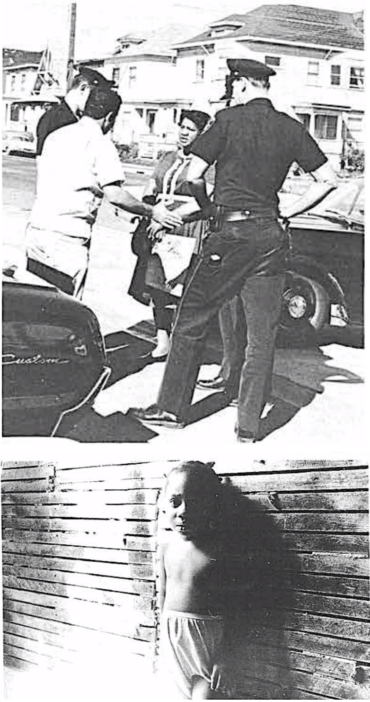

The Flatlands aimed to hold the powerful to account by capturing the repercussions of police violence (Lynn Phipps)

Flatlands staffers advanced the defense of Luther Smith, severely beaten in a case of mistaken identity by Oakland Police while executing a no-knock warrant. Flatlands contributor Curtis Baker brought the illegal home invasion and its violation of Smith’s civil rights to public attention. Smith’s suit against the Oakland Police Department, litigated by radical Oakland lawyer Robert Treuhaft, received support from sympathetic politicians like Democratic congressional candidate Robert Scheer. As the case gained traction, Flatlands contributors Mark Comfort and John George provided testimony to members of the United States Civil Rights Commission at local hearings in May 1966.

The Flatlands and its staff also played a role in the rise to national prominence of Oakland’s Black Panther Party for Self-Defense. Before becoming a revolutionary leader, Bobby Seale had worked for the North Oakland Target Area anti-poverty program, similar to many Flatlands contributors. As co-founder of the Black Panthers, Seale and his Party’s armed police surveillance patrols earned local grassroots credibility, but lacked a national profile.

When, on April 1, 1967, Richmond police shot an unarmed, 22-year-old Denzil Dowell in the back, The Flatlands’ Mark Comfort brought news of the killing to the Party’s North Oakland office. Stung into action, Panther leaders organized a series of protests leading to what national news media reported as an armed “invasion” of the California State Capitol building on May 2. The protest catapulted the Black Panthers to national renown and resulted in Governor Ronald Reagan signing the Mulford Act into law, rescinding the right to carry loaded weapons in public in California.

Challenging Segregation and Inequality in Oakland’s Public Schools

The Flatlands campaigned for the desegregation of Oakland public schools with mixed results. The depth of the problem could not be disputed: de facto segregation reflected neighborhood demographics, with majority-white schools in the hills disproportionately well-resourced, while those in the flatlands taught black and Hispanic students in crumbling, overcrowded, and underfunded facilities, using curricula that paid little to no attention to the Black experience in America. The War on Poverty and its funding requirements mandated substantial progress toward desegregation, but the Oakland Board of Education refused to provide adequate funding to such efforts, including a busing plan modeled on one in neighboring Berkeley. Satisfaction among students and parents plunged as a result.

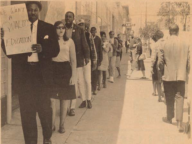

Led by Flatlands contributor John George, the Ad Hoc Committee for Quality Education (AHC) capitalized on community discontent in the fall of 1966 by calling for a three-day student walkout. As boycott planning ramped up, the AHC fought to increase funding for the Oakland schools free lunch program, organized pickets, and disrupted Oakland Board of Education meetings. To remedy overcrowded classrooms and abusive disciplinary measures, the AHC proposed “freedom schools,” staffed by its volunteers and modeled on similar initiatives in the South.

Judged in terms of concrete results, the boycott was largely unsuccessful. Police harassment of students at Castlemont High in East Oakland prompted demonstrations and violent clashes two days before the boycott’s scheduled start. City officials blamed the AHC campaign for stoking community unrest. Although the freedom schools went ahead as scheduled, the boycott proved to be a public relations disaster. Despite this disappointment, The Flatlands continued its advocacy for better understanding and relations between Oakland teachers and community members.

The Right to Fair and Affordable Housing

Oakland’s housing activists waged battles on multiple fronts in the mid-1960s. Urban renewal and mass transit programs initiated sweeping redevelopment schemes that caused mass displacement. Renters in privately held apartment complexes faced eviction. Although public housing accounted for a tiny portion of the city’s housing stock, by virtue of its scarcity, tenants were reluctant to speak out against mistreatment for fear of losing their home. From confrontations with BART to tenant activism, The Flatlands provided support and news coverage.

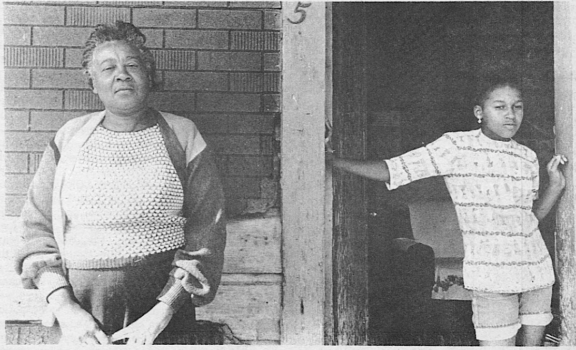

Marie Walker Johnson disputing an eviction; the evicted tenant’s young child (Lynn Phipps)

Many residents of West Oakland disdained the “block busting” tactics of the Oakland Redevelopment Agency (ORA), which launched its efforts with the total demolition and reconstruction of the Acorn district, displacing 9,000 residents. ORA’s “slash and burn”approach to urban renewal prompted the formation of neighborhood advocacy groups like Flatlands contributor Mark Comfort’s Lockwood Improvement League and West Oakland’s Peralta Improvement League.

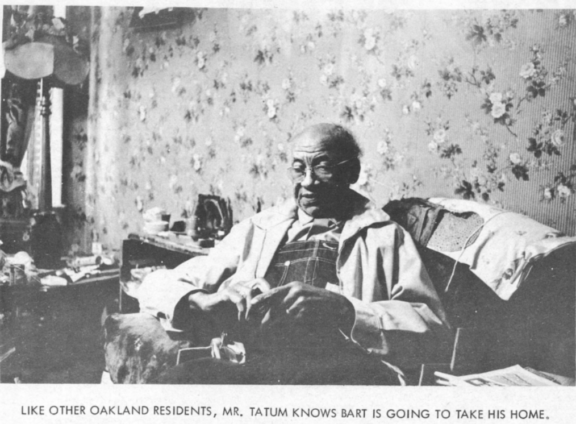

The greatest challenge for housing activists lay in the construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system. Its route through West Oakland threatened a black entertainment and shopping district centered on Seventh Street. BART offered compensation amounts well below market rates to owners of homes targeted for demolition. Adding insult to injury, almost all contractors hired by BART refused to hire local black workers, preferring to recruit white workers from out-of-state. In response, The Flatlands took pains to profile those in the crosshairs of BART’s development plans and promoted the efforts of Justice on BART (JOBART), an activist group that pressured city officials to increase the compensation offered to displaced residents and to ensure that BART contractors hired a a proportionate number of black workers.

Profiling those in the crosshairs of BART: the plight of Mr. Tatum (Lynn Phipps)

The Legacy of The Flatlands

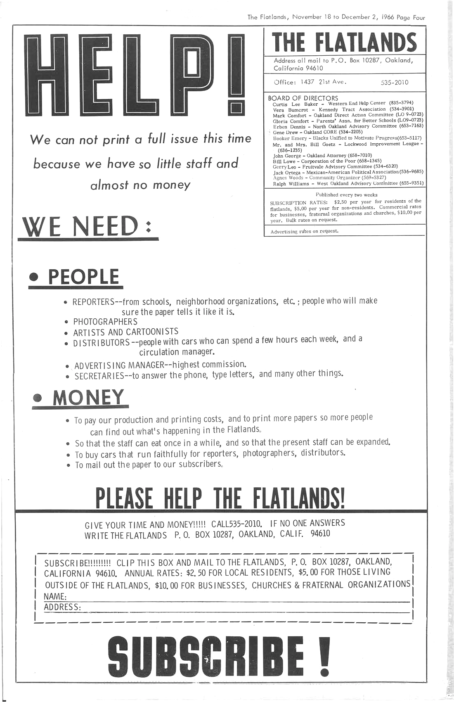

By late 1966, The Flatlands was desperate for volunteers and financial support

Like the communities it represented, The Flatlands fought against strong headwinds, blowing in from a number of directions. After its seed grant ran out, it endured ongoing money problems; full-page fundraising ads warning that the paper could not continue without financial support made little difference. As publicity-savvy contributors like Mark Comfort departed or reduced their involvement, publication became more intermittent.

The rise of the Black Panther Party as the leading edge of social change in Oakland also coincided with the newspaper’s decline — a case of one institution becoming overshadowed by another that it had fostered. The Black Panther ideology of community self-determination and radical egalitarianism drew strongly from The Flatlands; indeed, in their history of the Party, historians Waldo Martin and Joshua Bloom credit Mark Comfort and Curtis Baker as strong influences on Huey Newton and Bobby Seale. By 1967, the vanguard had become more militant and wider-angled in its vision of revolutionary change, and The Flatlands, by contrast, continued to be more engaged with neighborhood issues, with the emphasis on the community organizing that had been its hallmark.

The newspaper ceased publication in 1968, but its players continued to be active in political and cultural struggles, advancing new radical projects through the late-60s and beyond. Mark Comfort took a job in 1968 with Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Poor People’s Campaign. Richard York founded the Berkeley Free Church, which ministered to the transient street communities of Telegraph Avenue and sought to merge political and spiritual radicalism. Dr. Jack D. Forbes established a foundational place for himself in Native American studies, helping to establish one of its first programs in the nation at UC Davis in 1969. John George, who headed the Oakland school boycott, was elected to the Alameda County Board of Supervisors; to honor his lifelong work on mental health issues, the county’s psychiatric hospital in San Leandro bears his name.

Flatlands founding editor Alexandra Close—now known as Sandy Close—took over the editorship of Pacific News Service, a progressive news nonprofit, in 1974, and continued to build publications with a range of racially and ethnically diverse voices, receiving a MacArthur “genius” grant in 1995 for her work in transforming American journalism.

***

The work of The Flatlands, of course, remains radically unfinished. Oakland’s working class and poor are still concentrated in the city’s flatlands, where they continue to suffer from underfunded schools; unaffordable housing and predatory landlords; a police force that disproportionately targets people of color; and a city government that bends to the interests of the wealthy minority rather than the many who struggle to live in the city.

It is to The Flatlands’ credit, though, that it put its finger on the issues — radiating out from the stark inequalities that beset the city — that were most crucial to the health of Oakland then and continue to be most crucial to the health of Oakland now. Operating on a shoestring, it provided fine-grained coverage of everyday lives and on-the-ground struggles that rarely made it into the Oakland Tribune. The result was an extensive record of life in the flatlands, filtered through a sympathetic and powerful lens.

— Will Seaver

Will Seaver (Cal ’21) is a rising senior, majoring in history, with an interest in the domestic and international impact of US liberation movements on the Cold War.

Will Seaver (Cal ’21) is a rising senior, majoring in history, with an interest in the domestic and international impact of US liberation movements on the Cold War.

Acknowledgments

I would like first to thank my parents for their patience and helpfulness, and my friends Courtney Davison, Michael Glover, Jeff May and Kaylah Williams for all the love and support they have given and continue to give.

Jennifer Dorner’s assistance enabled me to move beyond my initial research questions and explore Flatlands-affiliated individuals and organizations more deeply. Similarly, the staff at the African American Museum and Library at Oakland and the Graduate Theological Union assisted me greatly in exploring their respective collections. Consultations with Camilo Lund-Montano also shaped the basic structure and conception of this project. P. Gabrielle Foreman and Susan Moffat provided essential feedback to an earlier version of the project.

Lastly, I would like to thank Professor Waldo Martin, whose seminar on twentieth-century social movements helped me center the experiences and voices of ordinary people, and who graciously discussed this project in his office hours; and Professors Scott Saul and Greg Castillo, who adopted my enthusiasm for this project and assisted in its conception, research and writing. The project greatly benefited from their efforts.

Additional Resources

A nearly complete archive of The Flatlands can be found at the Oakland Public Library’s website.

Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Black Against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013).

Cedric Johnson, Revolutionaries to Race Leaders: Black Power and the Making of African American Politics (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2007).

Chris Rhomberg, No There There: Race, Class, and Political Community in Oakland (Berkeley, Calif.; London: University of California Press, 2007).

Robert O. Self, American Babylon: Race and the Struggle for Postwar Oakland (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2003).

Robyn C. Spencer, The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

The Flatlands was in the business of making Oakland's leaders, who lived in the hills, accountable to those who lived below them