The Hunters Point uprising in southeastern San Francisco made massive nationwide headlines in September 1966. In the wake of Watts, Americans were still anxiously awaiting the next urban insurrection, and any incidence of racial unrest in a major city was a national news story. Just as with Watts, the proximate cause of the unrest was the police shooting of a young black man, Matthew Johnson. In the aftermath, multiple blocks of the neighborhood’s Third Street business district lay in ruins, and an intense atmosphere of recrimination against the police department had settled in.

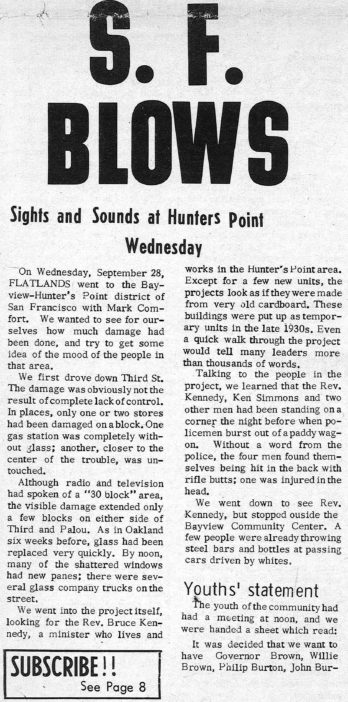

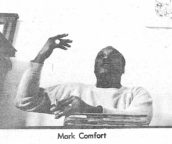

The Flatlands‘ coverage of the incident was threefold: a piece of on-the-ground reporting from the first night of rioting by contributor Calvin E. Booker, an Oakland resident who had driven to the scene after hearing reports of the disturbance; a report from the following day spearheaded by Mark Comfort, who interviewed residents and took assessments of neighborhood demands; and a piece of analysis by frequent contributor Norman Adams, who tied the rioting to other such recent incidents in Cleveland, Chicago, Omaha and elsewhere, quoting James Baldwin’s Notes from a Native Son on the perniciousness of white blindness to the underlying causes of urban black unrest.

***

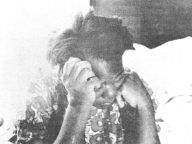

The paper’s coverage of the events, in total, reveals a variety of preoccupations shared by participants and observers of the events alike. As community leaders like Sun-Reporter publisher Carlton Goodlett pled for a peaceful, non-violent response, the crowd responded with vehemence and impatience: “This is an American problem; for 400 years, this is an American problem.” For how much longer, the crowd wanted to know, were they expected to wait for justice?

Interviews with participants and bystanders show us how they understood the use of mass uprisings as a political tactic, as a rational response to the repression and marginalization they experienced. In noting an undamaged service station on a devastated block, an observer reports that it “had always employed Negroes, and had been decent to the kids when they had very little money.”

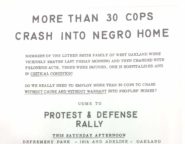

Certainly, the police remained one of the biggest obstacles to justice in their eyes, if not the biggest. It was an irony lost on the San Francisco Police Department that they were responding to civil unrest with the very behavior that had caused it, and The Flatlands‘ coverage emphasizes the paddy wagons and casual violence that were central to the police response.

It also reveals a growing awareness in the community of larger forces at work, and the need to organize collectively to combat them: to quote one resident, “We’re going to have to go beyond 3rd St. with this, we’re going to have to go downtown.” Aware of this challenge, and of the potential leverage that mass unrest could provide, the proposal collected by Comfort called for total disarmament of SFPD officers, a citizen-led investigation of police practices, and civilian patrols of police activities to promote accountability.