Occasionally, figures from The Flatlands came to the attention of a national audience. West Oakland community activist Curtis Lee Baker, for example, was extensively profiled in a January 1966 Los Angeles Times story, one of several from the time that examined Oakland’s potential for urban unrest in the manner of Watts. As Oakland anti-poverty activists began to organize and pressure political and business leaders for change, other groups began to take notice of their efforts as well.

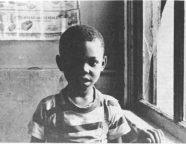

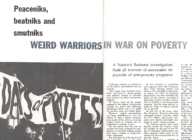

Among these was the United States Chamber of Commerce, then as now one of the country’s largest pro-business lobbying organizations. Its in-house organ, Nation’s Business, took an editorial line that reflected the Chamber’s conservative, anti-New Deal politics. This orientation is evident in the magazine’s May 1966 cover story about Bay Area left-wing and progressive activists. Its subhead — “Peaceniks, beatniks and smutniks” — reflects the journal’s political and cultural conservatism, invoking broadly-held stereotypes of the Bay Area’s reputation as a liberal and decadent free-for-all.

Above and beyond its objections to the bacchanalia of San Francisco and Berkeley, Nation’s Business hated Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Federal outlays to job training and economic opportunity programs were feckless wastes of taxpayer money at best and Communist-inspired at worst. The article targets anti-poverty workers and activists like Mark Comfort, John Ross and Howard Harawitz for their memberships and associations with Communist and Communist-affiliated organizations like the Progressive Labor Party and the DuBois Club, with Comfort singled out for smearing as a criminal and a violent agitator. Connections between Bay Area radicals and nationally-prominent “subversives” such as Bayard Rustin and the Marxist historians Staughton Lynd & Herbert Aptheker are spelled out in detail.

Filtering out the paranoid anti-communism and other obvious biases, the article paints an interesting picture of burgeoning solidarity between Berkeley students and Oakland activists. Dr. Norvel Smith, then-staff director for the Oakland Economic Development Council (OEDC) which coordinated federal anti-poverty funding, blasts UC Berkeley students for their efforts to support the Target Area Advisory Committee (TAAC) walkout for greater community control over the city’s anti-poverty program. The school’s community work-study programs, which often placed students in poor and black neighborhoods in Oakland, played a huge role in fostering social and political connections between Oaklanders and Berkeley students, and the boundaries between anti-war and anti-poverty activism were fluid; Smith singles out the Vietnam Day Committee, then the campus’ largest anti-war organization, as a particularly unwelcome and destabilizing presence in Oakland’s War on Poverty.