This editorial, from an early issue of The Flatlands, celebrates and endorses the recent walkout by anti-poverty workers seeking greater representation of the poor in the implementation of anti-poverty programs. The Economic Opportunity Act of 1964—one of the key pieces of legislation in President Johnson’s War on Poverty—had mandated that community-based anti-poverty programs be designed to facilitate the “maximum feasible participation” of the targeted beneficiaries. In Oakland, as in many other cities, this language proved to be a fulcrum that activists used to transform the standard workings of social services.

In Oakland, federal officials and city officials collaborated to create the Oakland Economic Development Council (OEDC), an appointed board of political, business and community leaders who were tasked with overseeing the disbursement of the city’s designated anti-poverty and economic development grants. Through the OEDC, four Target Area Advisory Committees (TAACs) were created to facilitate the provision of services in the city’s poorest neighborhoods: North Oakland, West Oakland, Fruitvale and East Oakland each had an elected committee of anti-poverty workers who were meant to carry out OEDC directives and advise the Council on street-level conditions. The TAACs themselves were paid through federal funding, but as the name indicates, they served (initially) no more than an advisory role in the actual decision-making of the Council itself.

From the beginning, the makeup of the OEDC board was a controversial subject among its intended constituents. The board’s few black members, most notably judge and future Council chair Lionel Wilson, represented the city’s black middle class and tended to live outside of the target areas; the city’s poorest lacked any direct representation on the board itself. TAAC members, much more deeply and intimately involved in the day-to-day workings of the poverty program than the board members, felt that the board’s unrepresentative makeup had a direct and negative effect on the quality of the services provided, and they began to demand that 51% of the board’s members be residents of the target areas themselves.

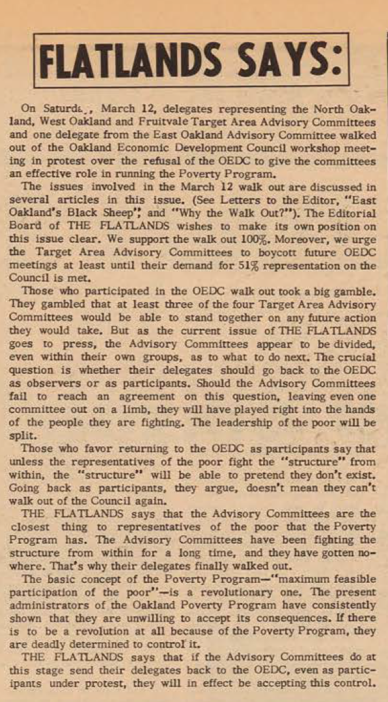

The paper’s position in the fight between the TAACs and the OEDC was by no means neutral. Many Flatlands contributors, including Agnes Woods,Ralph Williams, Gerry Leo and Booker T. Emery, were at one time or another TAAC members themselves, and the paper’s combative stance toward other civic institutions and authorities was doubly reinforced by this insider’s experience. The editorial notes that some TAAC members were concerned that by walking out, they would be jeopardizing their best chance at influencing the operation of the poverty programs, but praises the bravery and necessity of the majority decision, seeing it as a necessary step to achieve greater community control over necessary funding.