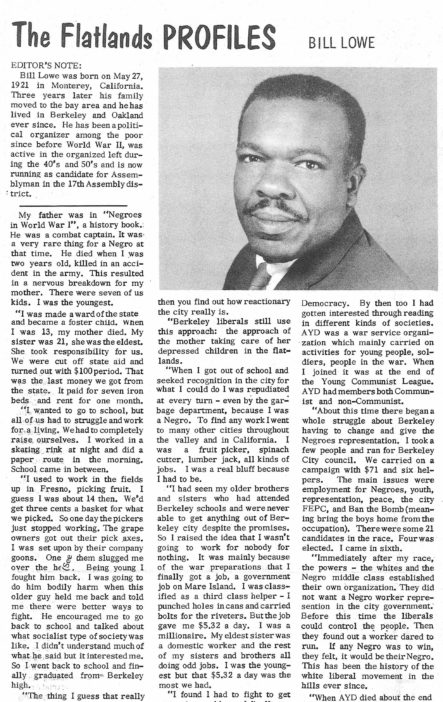

Flatlands editorial board member Bill Lowe brought decades of political experience, organizing workers on the Left, to the newspaper and to its project of organizing the flatlands as a community.

Raised in Berkeley, Lowe had a difficult, rocky childhood. His father, an Army captain during World War I, had died when he was two — a death which precipitated the nervous breakdown of his mother. A foster child, he was raised by his older sister after his mother, in turn, died when he was 13.

He was radicalized by the disjunction between the promises made by Berkeley’s educational system and the realities of job segregation in the city of Berkeley: having finished his education at Berkeley High, he found that even the city’s garbage department would not consider him for a job. Discouraged, he worked in the Central Valley and elsewhere as a fruit picker, spinach cutter, and lumberjack, until World War II (as it did for many Black Americans) opened a window of opportunity for him: a job as a “third class helper” on Mare Island, which he leveraged into a job as a “first class helper” and a traineeship, which in turn led to work as a submarine repairman.

Classified now as an “essential worker,” Lowe also began the series of political involvements that led him to The Flatlands. In the mid-to-late-’40s, he participated in American Youth for Democracy, which was affiliated with the Communist Party but aimed to bridge the Communist and non-Communist Left. In the 1950s—and through the era of McCarthyism—he served as the Western Regional chairman of the Marxist-oriented Labor Youth League, working full-time for the organization. (This pathway of activism—from American Youth for Democracy to the Labor Youth League—was the same radical itinerary traveled by the progressive scientist Leon Wofsky, who became a key faculty ally of the Free Speech Movement at UC Berkeley.)

After the Labor Youth League disbanded under the pressures of McCarthyism, Lowe lent his organizing prowess to the Bay Area AFL-CIO, becoming Vice-President of its political arm — though later he left the organization because he refused to abide what he saw as its politically compromised endorsement of Oakland Mayor John O’Houlihan.

He brought to The Flatlands a radical vision of grassroots democracy: “For me there was only one answer for the Negro and poor — someone to challenge publically [sic] the institutions that dominate and direct—the institutions of white liberals, Negro professors, self-perpetuating trade union leaders … they all have one goal in common — to guarantee that the working and poor people will never determine their own destiny and represent themselves in any halls of government. When they talk about unity it means a poor person can join their group if they do free work. But they have no voice in policy making.”

In its reporting and in the challenges it threw down to Oakland’s social services bureaucracy, educational system, and political establishment, The Flatlands would seek to give the poor that “voice in policy making” that, as Lowe suggested, had long been denied them.

***

Lowe’s Flatlands profile avoids another aspect of his radical life: his marriage to Jeanne Tobey, who was white. In May 1948, Lowe and Tobey defied California’s ban on intermarriage by traveling by train from Oakland through Oregon to Vancouver, Washington — one of the nearest states that did not ban intermarriage. There they visited a county clerk’s office, and a justice of the peace performed the marriage ceremony. Five months later, in October 1948, the California Supreme Court became the first in the 20th century to strike down a ban on intermarriage (though it took over a decade for the California legislature to vacate the statute, as the court’s decision was a controversial one).

Bill and Jeanne Lowe were both active members of American Youth for Democracy, and through that group they befriended a number of interracial couples. They remained married until Lowe’s death in 1995.