The Third World Liberation Front

This is the story of campus no one tells on tours when they walk by Sproul Hall.

It’s the story of how UC-Berkeley was enveloped in clouds of tear gas during the longest strike in campus history—how the campus was shaken, like the rest of the world in the 1960s, by the demands for justice by young Third World people. It’s also the beginning of the story of the longest-lasting social movement on the Cal campus—a movement that has mobilized for five decades and counting.

The Third World Liberation Front (TWLF) at UC Berkeley coalesced in 1969 to demand self-determination in education through the establishment of a Third World College, whose curriculum would be designed for, and taught by, people of color. But TWLF was about more than demands for a new course of study and representation. Through its vision of an open university, tied to and energized by communities historically excluded from college settings, it threw down a larger challenge to oppressive structures of power at the University, in the United States, and across the world.

TWLF at UC Berkeley didn’t arise in isolation. It was born out of a long legacy of struggle and resilience by ancestors across the diaspora, as well as a more immediate local struggle — the strike for Ethnic Studies led by San Francisco State University’s own Third World Liberation Front. (In January 1969—when Berkeley’s TWLF formed—the SF State strike was gaining momentum in its third month, with faculty joining the student picket lines.)

Coming together at the same historical moment as the Black Panther Party’s expansion across the country, the United Farm Workers’ grape boycott, the fight to save the International Hotel, and the occupation of Alcatraz, Berkeley’s TWLF placed its hope and love in communities of color, seeking to illuminate their histories of resilience and struggle within capitalism, white supremacy, imperialism, and the larger host of oppressive structures.

The Origins of the Strike (Spring 1968-January 1969)

The Third World was not a place. It was a project. During the seemingly interminable battles against colonialism, the peoples of Africa, Asia, and Latin America dreamed of a new world. — Vijay Prashad, The Darker Nations

In spring of 1968, the Afro-American Student Union (AASU) at UC Berkeley submitted a proposal for the creation of a Black Studies program. Declaring that Black students all over America were in state of crisis, the AASU demanded that the university implement “a program which will be of, by, and for Black people.” The AASU contended that the Black Studies program would offer a more relevant form of education for Black students at Berkeley. They expected the program to evolve into an autonomous department that would ensure that Black students would be educated rather than indoctrinated.

After persistent pressure by the AASU, Chancellor Heyns and the UC Regents approved a Black Studies program—not a department—on January 13, 1969. The proposal was viewed as a serious dilution of what the AASU proposed, a key issue being the absence of Black student and staff membership on the implementing committee. (The implementation and principles of Black studies could not be fulfilled without the autonomy and input of those who developed and envisioned it.) Infuriated at the University’s unwillingness to meet the original demands, the AASU rejected Heyns’s proposal.

Black activists at Berkeley turned to build a larger alliance: they joined forces with the Mexican American Student Confederation (MASC), the Asian-American Political Alliance (AAPA), and the Native American Student Alliance (NASA) under the banner of the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), inspired by the example of the Third World Liberation Front at San Francisco State. All the partners within the coalition hoped that, by organizing under a single united front, they could gain their own ethnic-focused programs.

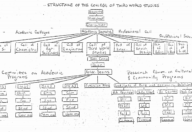

TWLF at UC Berkeley coalesced with the primary goal of starting a Third World College, which would incorporate departments with studies geared towards Black Americans, Mexican Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans. This Third World College would address the traditional Eurocentric education and incorporate into academia conversations on identity and oppression. It would also grant students of color self-determination: one of the main issues was that the University granted them no rights to question the education they were receiving.

The Strike Unfolds (January-February 1969)

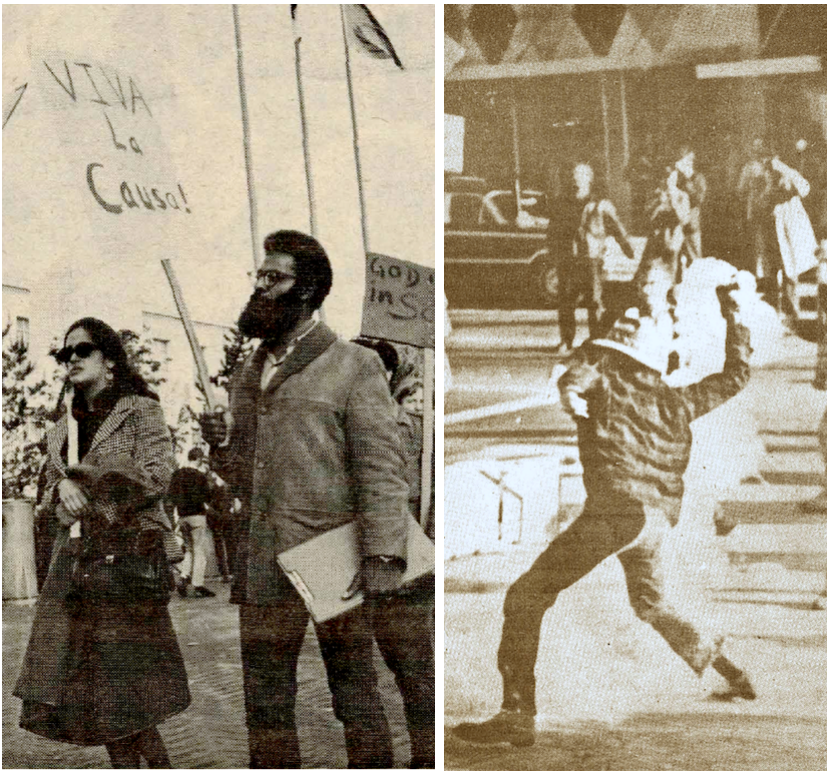

Mobilizing under the watchword of “self-determination,” TWLF launched a student strike on January 22, 1969. At first, the strike took the form of informational pickets at major entrances and buildings on campus, with the goal of building a broader base of support. Their formal demands included the establishment of a Third World College; the recruitment of Third World people at every level of university administration, instruction, and staff; open admissions for Third World applicants; institutional autonomy (“Third World control over Third World programs”); and amnesty for strikers.

Within ten days, the strike had ratcheted up in intensity. Smaller picket lines had mushroomed into gatherings of thousands, who marched serpentine-style across the campus; it was impossible for non-striking students to attend class without being made aware that they were crossing a picket line. Police, with the university’s cooperation, targeted strike leaders for arrest. More centrist campus organizations, such as the ASUC Senate, the faculty Senate and the Daily Cal, tended to support the goals of TWLF while raising questions about the tactics of the strike.

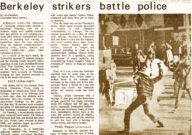

February 4 marked a turning point in the strike: when plainsclothes officers tried to arrest strikers in the middle of a demonstration, they touched off chaos—with pro-TWLF students beating back the arresting officers. Twenty were arrested, and twenty injured. The police then declared the demonstration an “illegal assembly,” and the next day, the campus administration refused to allow noon rallies on Sproul. Even more consequentially, both police and the campus administration appealed to Governor Ronald Reagan on February 5 to declare a “state of extreme emergency” on campus so that more police forces could be brought onto campus.

An Occupied Campus, an Ongoing Strike (February-March 1969)

Since the Free Speech Movement of 1964, there had been a history of police militarization in response to student activism on the Berkeley campus, but the active involvement of students of color in TWLF coincided with a new level of police presence and violence, as the campus entered a spiral of conflict. On February 13, police arrested 17 TAs on a peaceful picket line; this action led the TA union—which previously had narrowly refused to go on strike with TWLF—to vote to strike themselves, and the strike expanded to include the refusal of teachers as well as students to enter the classroom.

Chancellor Heyns declared, “Sather Gate will be kept open by any means necessary.” Within a week’s time, police had started using more aggressive tactics to suppress the strike, such as the use of mace and tear gas. In response, strikers threw the spewing tear gas canisters back at police and hurled other rough projectiles in their direction. The Daily Cal, which before had temporized on the strike, now backed it and editorialized that “The reign of [police] terror cannot longer be endured.”

As campus administration focused on arresting strike leaders (at least one of whom was knocked unconscious by police), the National Guard was brought onto campus for the first time — an escalating move that would be repeated later in the year, in connection with the protests around People’s Park.

The Aftermath of the Strike (March 1969-1974)

On March 4, 1969—after ten weeks of intense struggle on TWLF’s part—Berkeley’s faculty Senate voted overwhelmingly to establish a department of Ethnic Studies on the campus. The proposal was seen, by activists within twLF, as more of a “face-saving” method to end the strike rather than an actual resolution. twLF vowed to continue the fight for a Third World College: “under no circumstances should it be assumed that our Strike has ended,” it declared.

In the ensuing months, however, wavering support and internal divisions within the coalition slowed the movement’s momentum. The students were disappointed the strike had ended, and all they had to show for it was an Ethnic Studies department, which was bound by standard university protocols and set up to follow in the mold of every other academic program on campus. The administration was satisfied that things would be put off momentarily, leaving the promising Third World College in limbo.

The fight for Black Studies continued within the united front of Ethnic Studies. The settlement that ended the TWLF strike in 1969 placed the Ethnic Studies department under direct authority of the Chancellor. The members of Black Student Union (BSU) continued to advocate for an “autonomous” Afro-American Studies department. Ideally, they hoped for a spot in separate College of Ethnic Studies. By this time, most students who had participated in the original strike had either left the University or graduated.

The controversial Afro-American Studies coordinator at the time, William Banks, thought it suitable to assemble a department in the College of Letters and Science. The proposal coalesced into a plan for the Afro-American Studies curriculum to gain departmental status in the College of Letters and Science, and by 1974 the department was approved by the administration. Although several students and faculty members opposed the move, their pleas were to no avail. Ultimately the departure of Afro-American Studies from Ethnic Studies severely set back the dream of a Third World College.

Our Place in the Legacy

The story of Ethnic Studies at UC Berkeley (and many other higher education institutions) is one of struggle and resistance. Since 1969, every generation of students has mobilized to keep Ethnic Studies afloat, to carve space in an institution that never had them in its imaginary. The struggle that TWLF sparked has never ended: it continued with the hunger strike in 1999 for more funding, faculty, and the Multicultural Community Center, and the struggle in late 2000s for a permanent and visible space for the Multicultural Community Center, and has persisted every year in between.

This is the story of the shoulders we stand on, the legacy of struggle we have inherited to have our humanity fully acknowledged by the University, the United States, and the world. The vision of a Third World College at UC Berkeley has yet to be realized. It is our turn to remember that the 1969 demands of TWLF were just the beginning, the bare minimum — that it is a matter of educational justice for the University to support a curriculum that allows us to realize our full humanity as people of color. And it is our turn to remind ourselves that even when a Third World College is established, the movement has never been about mere bureaucratic demands.

So the revolution continues.

— Anthony Gilmore and Kai Nham

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Sine Hwang Jensen, Asian American Studies librarian at the Ethnic Studies library, who helped us get started and navigate the archives; Harvey Dong for inspiring this project and helping to fill in anecdotal holes; and all the original strikers—and all the people since—who have struggled to keep Ethnic Studies and the spirit of twLF alive.

Additional Resources

Asian Community Center Archive Group, Stand Up: An Archive Collection of the Bay Area Asian American Movement, 1968-1974 (Berkeley: East Wind Books, 2009). (Valuable curated collection of materials from Berkeley and San Francisco State’s Third World movements, as well as other protests such as the battle of the I-Hotel.)

Cecil Brown, Dude, Where’s My Black Studies Department? (Berkeley: North Atlantic Books, 2007). (A critique of Black marginalization on university campuses, with attention to UC Berkeley’s African American Studies Department.)

Ziza Joy Delgado, The Long Durée of Ethnic Studies: Race, Education and the Struggle for Self-Determination (

Harvey C. Dong, The Origins and Trajectory of Asian American Political Activism in the San Francisco Bay Area (dissertation in Ethnic Studies, University of California, Berkeley, 2002). (Detailed account of emergence of forms of Asian American activism out of the Third World Liberation Front strikes at UC Berkeley and San Francisco State.)

Seth Rosenfeld, Subversives: The FBI’s War on Student Radicals, and Reagan’s Rise to Power (New York: Picador, 2015). (Journalistic account, focusing on actions of activists, campus administration, and Governor Reagan’s administration.)

Ula Taylor, “Origins of African American Studies at UC Berkeley,” The Western Journal of Black Studies 34:2 (Pullman: Washington State University, 2010). (A historical account of the emergence of African American Studies on the campus.)

Third World Strike at University of California, Berkeley collection, 1968-1972. (The primary archive of materials on Berkeley’s Third World Liberation Front, available at the UC Berkeley Comparative Ethnic Studies Library.)

Ling-chi Wang, History of Ethnic Studies at Berkeley: Ethnic Studies 98/198 (Berkeley: University of California Berkeley, Department of Ethnic Studies, 2011). (Compilation of primary materials, available at the UC Berkeley Comparative Ethnic Studies Library.)

Early pickets in January 1969; a street fighter tosses a tear gas canister back at police in February 1969 (photos by Hoffman/Barb, Grover Wickersham/LNS)