Berkeley’s Public Schools

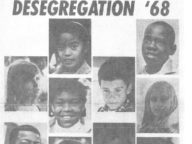

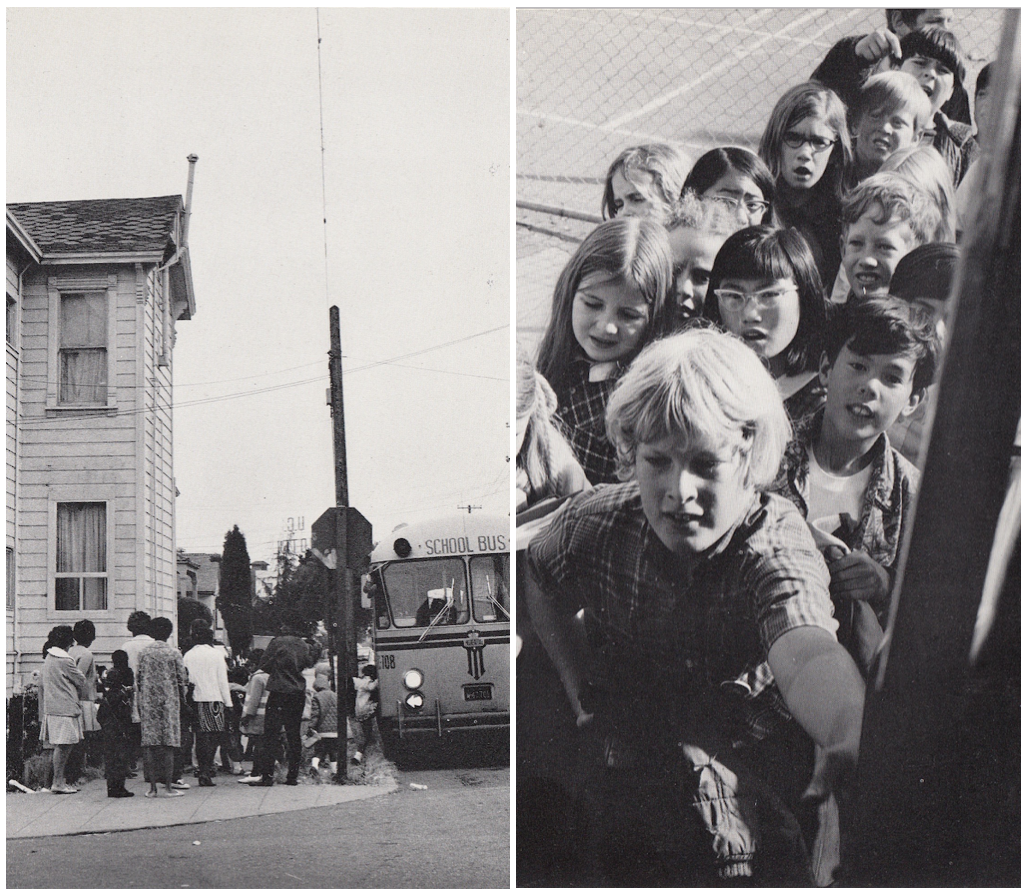

On September 10, 1968, the first day of a new school year, the buses rolled in Berkeley.

These thirty yellow school buses took on great significance within Berkeley, and as a headline in a larger national story about school desegregation. Martin Luther King Jr. even testified that, when it came to the project of school desegregation, it was only through the example of Berkeley that “Hope returned to my soul and spirit.”

As many observers noted, the Berkeley buses represented a historical watershed: for the first time, an American city had voluntarily adopted a two-way busing scheme involving the interchange of both white and black students.

The busing scheme, however, was only part of a much broader program—driven by the activism of Berkeley’s NAACP chapter—to make good on the constitutional rights of black children and desegregate Berkeley’s schools on all levels. School curricula, from history and English to languages and math, had to be adjusted or overhauled; the old tracking system, which tended to separate white students from black students, would be dismantled. The school system itself would need to desegregate its workforce, especially the largely white ranks of its teachers, as well as address inequities of pay on the lines of gender and race.

The project of desegregating Berkeley’s public schools intersected, consequentially, with another project in Berkeley educational circles in the late-’60s: the questioning of traditional models of education in favor of approaches that would be more student- and community-oriented, and more democratic in method. Inspired often by the “free schools” movement, educators launched a fleet of new schools, some oriented toward particular areas of the curriculum (the arts, reading), some oriented toward projects of ethnic or racial uplift and engagement, some oriented toward both at once.

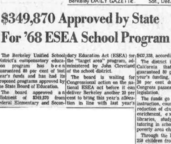

These schools—consolidated under the Berkeley Experimental Schools Project (BESP)—expanded through $6 million in funds from a federal government that, in the early 1970s, was aiming to seed innovative approaches to education. As a consequence, they were also vulnerable to federal cutbacks and conservative resistance to both educational experimentation and desegregation.

Throughout the early-to-mid-’70s, the larger Berkeley community was roiled over how to adjust to a new age of enforced austerity, part of a turbulent battle over the meaning of equitable education. By 1973, the school board made a point of distancing itself from the experimental spirit of previous years. In 1975 a protracted teacher’s strike—the first in Berkeley city history—put new pressure on the relationship between teachers and parents of color.

The legacy of Berkeley’s desegregation initiatives remains profound—evident in the shape of Berkeley’s schools today, as well as the buses that continue to roll between Berkeley’s wealthiest neighborhoods and its poorest.

Putting the Buses in Motion (1968)

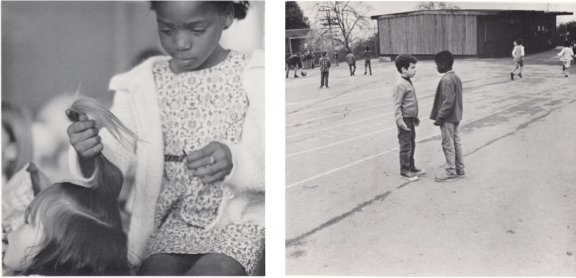

Practically, Berkeley’s desegregation plan meant that the youngest black students from the working-class ‘flats’ (kindergarten through 3rd grade) were bused to the predominantly white schools of the more affluent ‘hills’, while the slightly older white children from the hills (4th through 6th grade) were bused to the predominantly black schools of the flats.

Those school buses were significant for extending the project of desegregation to elementary school-age children who had before attended ‘neighborhood schools’ that reflected residential patterns of segregation. This was a hard-won victory for the local chapters of the NAACP, CORE, and a larger interracial progressive coalition that formed around the issue — one that beat back a 1964 effort to recall desegregation advocates on the school board.

Community preparations for the start of the 1968 school year were intense, as the many partners in that interracial coalition invested energy in a successful outcome. Teachers from the flats partnered in an exchange with teachers from the hills; almost all of the city’s 1100 fifth graders went to an outdoor education camp for two days; and many Berkeley community organizations—churches, synagogues, scouting groups, the YWCA—sponsored discussions and outreach efforts.

According to many observers at the time, the busing program itself was successful on its own terms — successful, most importantly, in redistributing educational resources more fairly, but also successful in launching a new experiment in crosscultural learning, where classrooms were marked not by demographic homogeneity and single-mindedness of approach but rather by diversity and flexibility of teaching method. While not free of tension, the newly integrated elementary schools allowed new relationships to form and new teaching strategies—strategies that recognized differentiated learning—to develop.

Photographs from The Buses Roll (Carol Baldwin and Peter T. Whitney)

An Age of Educational Experiment Is Launched (1969-1971)

In January 1969, six hundred of Berkeley High’s 1054 tenth graders applied for 108 spots in a newly formed “Community High“—a sign of the great initial interest, among students, for alternatives to traditional educational curricula, structures, and teaching methods.

Over the next several years, this interest on the part of students was met by a flurry of new “schools within a school” designed by local educators, and realized financially by seed money from private foundations (the Ford Foundation, the Carnegie Foundation) and later by grants from the federal government. In all, twenty-three schools were launched under the umbrella of the Berkeley Experimental Schools Project (BESP).

Community High (later Genesis) was conceived as a small-scale radical alternative to the impersonal, large urban high school. Grades were to be deprioritized; students were supposed to engage in cooperative learning with teachers, rather than simply be instructed by them, and were given substantive channels of input into school planning. It was, in short, an educational experiment in tune with the larger countercultural critique of American bureaucracy and American democracy.

It was also largely white. White students made up 70 percent of its original class, even though whites were only around half of Berkeley’s larger school population. In its first year of operations, its staff considered how to boost the representation of students of color, lest it become merely a ‘white hippie school’.

Simultaneously, Buddy Jackson—a Black Studies instructor-consultant at Community High—engaged in discussions with black students there about the need for another new school: one that would combine targeted instruction in basic skills with instruction that was oriented around black history, black culture, and the black experience. (Berkeley High, it should be noted, had already pioneered in developing a Black Studies curriculum.) Out of these discussions was born Black House: a school where education would be seen as “more than something ‘the man’ says one has to go through.”

From its inception, Black House was surrounded by controversy. As the authors of an in-depth study of Berkeley’s experimental schools suggested, it sounded “a discordant note amid the still-resounding echoes of self-congratulation” about Berkeley’s desegregation efforts. In a striking act of resistance to the project, Berkeley High’s counselors at first refused to hold counseling conversations with Black House students.

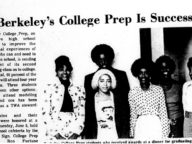

At the same time, Black House was aligned with several like-minded experimental public schools that opened in Berkeley in the coming years. Casa de la Raza, Agora, Kilimanjaro, College Prep, and Yoga/Reading all attempted to model a curriculum and pedagogy that would respond to the specific concerns and needs of minority students.

The push to develop ‘experimental schools’ within Berkeley received a huge boost when, in June 1971, the United States Office of Education (USOE) awarded Berkeley $3.6 million to fund the BESP for thirty months.

Controversial Once More: Federal and Local Pushback to Berkeley’s Experiments (1971-1975)

The same month that the BESP received its multi-million dollar grant, it ran into strong political resistance in the form of seventy-five year-old Senator John L. McClellan (D-Arkansas), who questioned whether Black House and Casa de la Raza were promoting a new form of school segregation. This was an ironic accusation coming from a politician who had publicly denounced Brown v. Board of Education and resisted the desegregation of Arkansas schools: segregation, it seemed, was fine when imposed upon black communities but, in McClellan’s view, against the law when tied to a black community’s attempt at self-organization.

Spurred by McClellan, the federal Department of Housing, Education, and Welfare (HEW) launched an investigation to determine whether Berkeley’s Experimental Schools were promoting a form of segregation. Neither Black House nor Casa de la Raza were, in their rules of admission, excluding white students—but was this a form of de facto segregation? Berkeley educators noted, in defense of the projects, that white students simply chose not to participate in such schools, whether out of either personal discomfort, disinterest, or some combination of the two. One legal scholar intricately parsed the issues at stake.

The BUSD line of argument did not carry the day. HEW decided that Black House and Casa de la Raza were “in probable non-compliance” with civil rights law, and threatened federal grant funding—not just for all BESP projects, but for federally sponsored literacy programs too—if the schools were not shuttered. When, in response to HEW’s objections, a local group fashioned an “Alliance Proposal” that would give students more curricular pathways by bringing several different experimental schools together—a project that had the flavor of the curriculum designed by the Third World Liberation Front at Cal—HEW rejected that plan as well.

Meanwhile the BUSD struggled to find its way. An accreditation board raised questions about the alternative sub-schools housed within Berkeley High. In April 1972, the school superintendent who had sponsored the BESP announced his intent to resign, effective at the end of the 1972-73 school year. When the BUSD authored a large-scale federal grant proposal to address minority underachievement in the spring of 1973, members of the School Board were skeptical: one board member declared “This district is not really interested in grantsmanship anymore.”

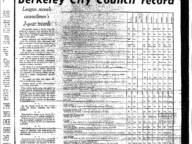

In Berkeley city politics, a center-right coalition proposed a telling amendment to how the city council would be elected. Through “Amendment M,” they called for runoff elections as a way to ensure the rule of the majority. This procedural change was clearly aimed at the rising class of black and female progressive politicians in Berkeley. As the partisans of Amendment M proclaimed in all-caps, “BERKELEY VOTERS HAVE GIVEN A MAJORITY [OF CITY COUNCIL POSITIONS] TO BLACKS AND WOMEN IN THE PAST AND UNDER MEASURE M WILL HAVE A BETTER OPPORTUNITY TO SUPPORT RESPONSIBLE CANDIDATES OF ANY AGE, SEX, OR RACE. YOUR VOTE FOR MEASURE M WILL GIVEN AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO EVERYONE.”

The supporters of Amendment M tried to harness the language of ‘equal opportunity’ to limit minority representation. Their gambit failed in the short term: in November 1972, voters rejected the measure. But the campaign foreshadowed a larger pushback against the desegregation initiatives that had been incubated in the late-’60s and early-’70s.

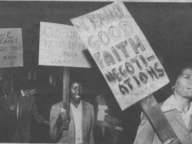

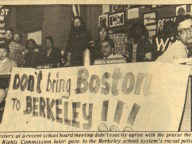

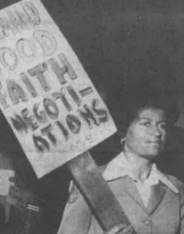

Protesting the new, more moderate School Board (Photo by Dave Patrick)

In April 1973, just five months after Amendment M was defeated, Berkeley voters elected a coalition of moderate Democrats to both the Berkeley city council and school board while rejecting a more radical slate. The center of political gravity of the school board would be held by figures like Gene Roh, a probation officer who proclaimed the cause of “quality education”; Marc Monheimer, a school board veteran who viewed the early 1970s as a time of “chaos and disarray”; and Louise Stoll, who recommended that the Board stop rubber-stamping new programs. This power bloc on the school board would continue to spark resistance from black parents and activists, who questioned the withdrawal of support from the BESP as well as the new board’s perceived lack of interest in community input in general. Nonetheless, the new center would hold.

School Workers and Labor Struggles in an Age of Cutbacks (1973-1976)

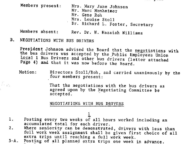

While Berkeley’s thirty yellow school buses were the central symbols of Berkeley’s desegregation efforts, not much attention was paid to the actual people driving those buses—a group of predominantly black women who were underpaid compared to the truck drivers, overwhelmingly male, who handled school maintenance and deliveries. For two school days in mid-September 1973, those women refused to be invisible. In an impressive show of unity, all 32 bus drivers called in sick to protest their unequal pay and the district’s defunding of field trips. They quickly won concessions from the school board.

While Berkeley’s thirty yellow school buses were the central symbols of Berkeley’s desegregation efforts, not much attention was paid to the actual people driving those buses—a group of predominantly black women who were underpaid compared to the truck drivers, overwhelmingly male, who handled school maintenance and deliveries. For two school days in mid-September 1973, those women refused to be invisible. In an impressive show of unity, all 32 bus drivers called in sick to protest their unequal pay and the district’s defunding of field trips. They quickly won concessions from the school board.

The bus drivers’ ‘sick-in’ speaks to a relatively untold story within the larger history of Berkeley school desegregation: the desegregation of Berkeley’s school workforce and the labor activism, across its ranks, that pushed back against cuts to the public sector made in the name of austerity.

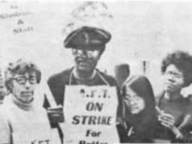

The elusiveness of solidarity (cartoon from Weather Underground piece on the Berkeley teachers’ strike)

The demographics of Berkeley’s school workforce spoke to the class stratifications of the larger East Bay. Older teachers were largely white. Between the late-60s and mid-70s, affirmative action policies—themselves disputed—helped recruit people of color into roles as both “certified” employees (credentialed teachers) and “non-certified” employees (the educators who often filled out the ranks of the experimental schools and taught in new programs like Ethnic Studies). Bus drivers and cafeteria and custodial staff—”classified employees”—were often people of color.

The teachers’ strike of 1975 put the solidarity of the full school workforce to the test, and at first it was weakened by fractures between teaching staff and classified employees. The strike itself had been touched off when the School Board, after discovering a ballooning deficit, had defaulted on an earlier agreement (one that protected the jobs of non-certified educators) and had instead insisted on a 2.5% cut to teacher salaries. Teachers voted by a large margin to strike and put up picket lines. Meanwhile, classified employees voted by a small margin not to strike, which allowed the schools to run with the help of non-union teachers imported from elsewhere.

The teachers remained on the picket lines for a full 33 days. Most students did not cross them: two weeks into the strike, less than 2,000 of Berkeley’s 14,000 students were attending school. In order to appeal to working-class parents of color especially, the union set up alternative classrooms in local parks: parents who needed to work could drop off their children for the day.

The teachers remained on the picket lines for a full 33 days. Most students did not cross them: two weeks into the strike, less than 2,000 of Berkeley’s 14,000 students were attending school. In order to appeal to working-class parents of color especially, the union set up alternative classrooms in local parks: parents who needed to work could drop off their children for the day.

The outcome of the strike was, depending on one’s perspective, either a modest victory or a draw for the teachers, with teachers staving off salary cuts and layoffs but making little headway on non-salary issues. Observers came to different conclusions about whether the strike had knit together teachers and parents, or teachers and classified employees, in a new sense of alliance. (One data point: Berkeley public school enrollments declined by 809 students the following year.) As with the larger project of desegregation, there were some promising signs of progress along with a continuing sense of structural difficulties.

Through the 1970s, Berkeley’s school workforce would continue to negotiate the terms of its employment under conditions of fiscal austerity—conditions that worsened structurally after 1978, with the passage of Prop 13, which undercut the amount raised for public education through local property taxes.

Eight Years Later, Divergent Views on Desegregation

The spring of 1976 became a flashpoint for reassessment of Berkeley’s desegregation efforts when — just in advance of a visit from the California Advisory Committee to the US Commission on Civil Rights, with the purpose of investigating school desegregation in the city — superintendent Laval Wilson offered a sobering assessment of how far Berkeley remained from achieving the goal of full educational equality.

Wilson’s assessment, it should be noted, was made in the context of an application for a federal grant of $463,000 to continue the sorts of special academic and multicultural programs which were at the center of the city’s desegregation efforts.

Wilson’s analysis was picked up and framed in a number of ways. The Berkeley Gazette — a publication that had long criticized desegregation efforts — underlined its darker strains, blasting a banner headline of “Desegregation is failing to meet education goals.” The Los Angeles Times ran a long piece investigating the struggles of the district, which ended with the older voice of white liberal Carol Sibley, decrying black separatism and militancy.

Meanwhile the Oakland Post, which served the East Bay’s black community, took Wilson’s analysis to suggest a different conclusion: that the journey to racial justice was long, and that it made sense to stay the course.

When the US Commission on Civil Rights—whose main brief was to investigate equality of education—released its report a year after its hearings in Berkeley, the commission largely echoed the point-of-view of the Post. Its report carried a tone of qualified optimism about the gains made in minority test scores and minority hiring.

These divergent takes on Berkeley’s desegregation efforts suggest how much the evaluation of the project depended on the eyes of the beholder. Was busing necessary to remedy the violation of black children’s civil rights? To achieve a beloved community? To raise test scores? All or some or none of the above?

In his book Why Busing Failed (2016), historian Matthew Delmont has suggested that media organizations played a large role in the ‘failure’ of busing because they mis-framed the issue: on a national scale, the debate over busing came to revolve around the feelings and opinions of white people, rather than around the constitutional rights of black children to an equal education.

Likewise, in reports on Berkeley’s desegregation initiatives, the concerns of black children, black parents, and black community members were often not at the center of the narrative — even though it was impossible to understand the need for these initiatives without their perspectives.

Mary Jane Johnson, a President of the Berkeley chapter of the NAACP as well as longtime Berkeley School Board member, offered this reflection on the distance between 1968, when the buses first rolled, and the mid-1970s: “The desegregation fight was a mechanical problem that involved logistical information and the temper of the community at the time. To desegregate, you simply put kids in buses and watched them roll. What we’re fighting now is institutional racism, which is a more complex problem and requires more complex solutions.” She added, “I don’t know that this community will ever come to grips with any problem with the same energy and intensity and group spirit that it did with desegregation.”

***

We hope that the documents curated here allow others to delve into this important episode in the history of Berkeley, in the history of desegregation in the US, and in the history of educational experimentation in the US.

— Linda Barghi, Scott Saul, and Kristen Wilson

Additional Reading

Susan Frelich Appleton, “Alternative Schools for Minority Students: The Constitution, the Civil Rights Act and the Berkeley Experiment”, California Law Review, 61:3 (May 1973).

Robert Coles, with photographs by Carol Baldwin and Peter T. Whitney, The Buses Roll (New York: W.W. Norton, 1974).

Matthew F. Delmont, Why Busing Failed: Race, Media, and the National Resistance to School Desegregation (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2016). (digital companion)

David Kirp, Just Schools: The Idea of Racial Equality in American Education (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1982).

Daniel H. Perlstein, Justice, Justice School Politics and the Eclipse of Liberalism (New York: Peter Lang, 2004).

Russell Rickford, We Are an African People: Independent Education, Black Power, and the Radical Imagination (New York: Oxford University Press, 2016).

Neil V. Sullivan, Now Is the Time: Integration in the Berkeley Schools (foreword by Martin Luther King, Jr.) (1969)

Other Resources Online

Berkeley Unified School District Minutes (1970s)

Berkeley High Yearbooks (all digitally available)

Mapping Inequality; Redlining in New Deal America (East Bay housing segregation)

A pioneering experiment in two-way busing (photographs from Carol Baldwin and Peter T. Whitney, The Buses Roll)