The Asian Community Library

“The library now has an added responsibility to the disadvantaged, ethnic minorities, illiterate and semiliterate, the institutionalized, and the aged.”

— Judy Yung

In Oakland’s Chinatown resides a busy, buzzing community center—an often unquiet space that is, in fact, a historic Asian library. The Asian Community Library, later renamed the Asian Branch of the Oakland Public Library, was the first Pan-Asian public library in the United States.

It emerged out of a moment of activism on the part of radical librarians, who called for the reimagination of the role of the library and sought to liberate the library in the spirit of the other movements—for Third World liberation, women’s liberation, and gay liberation—that had inspired them.

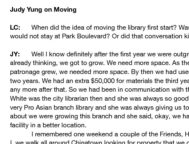

Judy Yung, the Asian Community Library’s first head librarian, spearheaded its development and shaped it in tune with the Asian-American movement of the 1970s. From 1975 to 1981, she attracted a culturally fluent and multilingual staff, built up collections, and organized programs to serve a local demographic—Oakland’s Pan-Asian community— that had been critically under-served and rendered invisible.

In the process, she and her coworkers helped bring that community to light: the Asian Community Library played no small role in raising Asian American visibility and helping the new racial category be recognized by government institutions—specifically, by the library system and the city of Oakland.

(A video made on the occasion of the Asian Community Library’s 40th Anniversary)

Reimagining the Role of a Library

In the late-1960s and 1970s, radical librarians pushed American libraries to shift their sense of mission. Following the demands for visibility, justice, and equality from social movements of the 1960s, these librarians recognized how their institutions lacked material that expressed radical or otherwise challenging political perspectives, as well as material concerned with minority experiences. Library activism, primarily led by feminist librarians such as Celeste West, sought to expand their catalog to serve marginalized communities and foster their self determination. These communities were publishing their own magazines, rewriting history, and redefining their identities, and librarians found it instrumental to collect these materials for public use.

Raised in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Judy Yung frequented her neighborhood library in her youth. When she was hired in 1972, San Francisco’s Chinatown Branch gained its first Chinese-speaking head-librarian. She was tasked to develop Chinese language material for the local Chinese population. Yung, who had worked in San Francisco’s public library system since 1964, carried many of the same frustrations and visions of these radical librarians.

Working in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Yung witnessed the Asian American Studies movement. The term “Asian American” was established in 1968 by Yuji Ichioka and Emma Gee, students at UC Berkeley and participants in the Third World Liberation Front. Yung brought the political ideology of the Asian American movement into her work. She dedicated herself to a mission of multilingual representation, culturally relevant and educational programs, and community involvement. To serve working class and immigrant communities, Yung brought to public libraries the demands for inclusivity and multicultural values that student activists fought for in universities.

‘“The library now has an added responsibility to the disadvantaged, ethnic minorities, illiterate and semiliterate, the institutionalized, and the aged,” she said, widening the sense of the “public” that would be served by the public library. “The public library must start hiring minorities and socially conscious people who can best understand and meet the needs of these people.”

In 1975, Yung was the first person hired to develop the Asian Community Library in Oakland. The project was proposed nine years after the opening of the Latin American Library Branch in 1966, the first library dedicated to servicing a Spanish speaking community in the U.S. Following the success of the Latin American Library, the Oakland Public Library supported an initiative to create a branch serving Oakland’s Asian population. Sumi Yamashita wrote the new branch proposal in a funding application to the Library Services and Construction Act (LSCA), a federal grant program that funded library services for minority and disadvantaged communities. The LSCA grant provided $300,000 to be used within two years. The Asian Community Library would be the first Pan-Asian library in the U.S., and Yung was given full reign to develop the library from scratch.

Developing the Collection, Outreach, and Programs

After being hired, Yung had just a few months to plan a library slated to open on the first day of March in 1976. She spent those months structuring community involvement and recruiting qualified staff. From the beginning, Yung knew that the library had the potential to serve Asian and Asian American populations located beyond Oakland. As part of the Asian American Movement, multiple Asian organizations were blooming across the East Bay to provide the basic services such as healthcare that government institutions failed to provide. The growing network of Asian organizing was a resource the Asian Community Library would add to and draw from.

Multilingual Staff Body

A multilingual staff was essential to successfully implement the Asian Community Library. Unable to hire librarians with her limited budget, Yung employed library assistants who were bilingual. Client services targeted five main ethnic groups: Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Filipino, and Vietnamese. Staff not only responded to questions related to library services, but served as a community reference and referral service to connect library patrons with available resources. Immigrants unable to speak or read English came by for help from staff to translate their mail. Yung’s new library was a flexible, multi-service institution.

Organizing Friends of the Asian Library (FAL)

Yung believed outreach was essential to gain patronage, involvement, and input from the ethnic communities that the library aimed to serve. Yung organized Friends of the Asian Library, a group of representatives involved in their respective Asian American communities, to assist with outreach, book orders, fundraising, and advocacy.

They were intentionally recruited to connect the library to multiple Asian American organizations in the Bay Area as well as institutions like Merritt College and UC Berkeley, thereby building a network of support. Early board members included Bill Sato, professor of Asian American studies at Merritt College; Jeff Leong, participant in the Third World Strike at UC Berkeley; and Lillian Galedo, library assistant for Asian American Studies at UC Berkeley. FAL meetings included discussions on issues within the library and around the community.

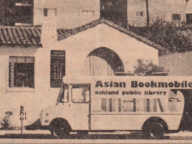

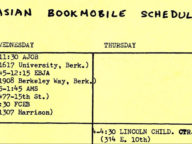

Bookmobile

“We need to go to Chinatown and other parts of the city where there are Asian immigrant populations.” — Judy Yung

The Asian Community Library found its first home on Park Boulevard, a site far enough away from Chinatown to make access a problem. In response, the Asian Bookmobile was used to make library materials accessible to those who lived in or frequented Chinatown. Bookmobile stops included Lincoln Elementary School, Lincoln Square Park, and ESL class locations in Chinatown. The bookmobile also made stops in Berkeley at Asian American organizations including Asians for Job Opportunities in Berkeley (AJOB). The Asian Bookmobile represented a commitment to extend services and resources outside the facility’s location in order to reach the intended population.

Programming

“Each Saturday the library sponsors a children’s program of storytelling, films, and crafts. Each month a program featuring a speaker, a film, or a cultural presentation is planned for the public.”

To build patronage for the library, programs were organized to gather the community. Events included poetry readings, classes, workshops, and performances that the community could attend for education or entertainment. These programs not only built community, but also brought people into the library’s physical space and raised awareness of available resources.

Building the Library Collection

Efforts in outreach, community building, and programming were highly successful, demonstrating the need for an Asian library. Library staff cultivated a collection of material in print that patrons could learn from and relate to. They also made available audiovisual material that educators could borrow. Popular library items included martial arts books, records, and cassette tapes in Asian languages. The Asian Community Library was one of the only places that offered cost-free access to recreational books and music in Asian languages. Immigrants far from their homelands were able to find and enjoy media in their own language without shame.

With Asian American studies just emerging as an academic field, little had been published about Asian American identity and experience in the US. Envisioned as a resource for Asian Americans, the library partnered with UC Berkeley to identify relevant materials and ordered them as well for the Asian Community Library. Works by Asian Americans about the Asian American experience, when offered by a public library, became accessible to a broader audience beyond university students.

Challenges with Funding and Space

Limitations from the Lack of Funding

While the Asian Community Library was well supported by Lee White, director of the Oakland Public Library, lack of funding was an obstacle. The inadequate budget limited the number of staff the library could hire and the materials it could buy, which affected the ability to serve each ethnic population in its language. When applying for re-funding and speaking to the Task Force on Cultural Minorities on behalf of the Asian Community library, government institutions had to be reminded repeatedly of the demographics and needs of the Asian American community. Funding was never easily granted. The library had to prove its effectiveness through its number of patrons and advocate for its budgetary lifeline.

“There’s Not Enough Space”

The Asian Community Library moved several times before arriving at its current location. It was first an addition to the Park Boulevard Library Branch and allowed to use half of the facility. The space proved far too small. The Asian Community Library soon became one of the busiest libraries in Oakland.

Judy Yung and two members of FAL, Henry Woon and Doug Wong, walked through Chinatown looking for properties that could accommodate the library. They envisioned a library in the heart of Chinatown, visible and accessible to the population they served.

In 1978, the Asian community library made a temporary move into the basement of Oakland’s Main Library, and then in 1981, to a storefront in 9th and Broadway. The facility, three times the size of the earlier Park Boulevard location, had large streetfront windows. At a glance, one could see how busy the library was. This first location in Chinatown was adjacent to supermarkets and businesses, allowing parents to drop off children at the library while they shopped and ran errands. The location saw even greater increases in patronage and circulation rates, and again the library rapidly outgrew its space.

More than Just a Library

Discussions about gaining a new space through the Chinatown redevelopment project preceded Yung’s resignation as head librarian in 1981. Chinatown’s urban redevelopment scheme offered new opportunities and challenges. The city of Oakland, property developers, Chinatown business owners, and Asian community-based organizations were all stakeholders, bringing to the table different ideas and visions for Chinatown’s future. As an important resource that was fundamental to the community, the library found it critical to be a part of the conversation..

(Lillian Galedo interviewed about the move of the Asian Community Library to Chinatown)

The library joined a coalition of several Asian American and Asian ethnic organizations committed to holding developers and the city of Oakland accountable to their visions and demands for Chinatown. Asian organizations repeatedly asserted their demands to include the community in the decision making. Siding with Asian community-based organizations, the library advocated for affordable housing and a cultural center where it could occupy a ground floor space. Eventually, the Pacific Renaissance Plaza would be constructed in 1993, with the library relocating to the new facility in 1995.

The Asian Community Library’s success and struggles are part of a larger story of how Asian Americans and other marginalized populations pushed for inclusion within institutions from which they had previously been excluded. Asian Americans mobilized to head their own programs and agencies, creating new service structures and networks. They raised the standard of what public institutions should provide for its people by taking on leading roles.

Through its multilingual and multiethnic programs and outreach, the Asian Community Library was among several Chinatown organizations at the forefront in defining the new racial category of “Asian-American” in Oakland. Pan-Asian organizing was used to gain power and visibility with greater numbers. It secured government funding that favored multi-ethnic programs impacting the greatest possible number of people. As a project supported by the city, the library institutionalized and provided political recognition for the new notion of a Pan-Asian population.

The Asian Community Library, however, acknowledged that it could not aggregate the multiple identities of patrons and sought to differentiate each ethnic group within the pan-Asian umbrella. Indeed, during the library’s early development, the ethnic components of its target population shifted substantially, making the development of library collections a far more complex task, given the limited budget. The Immigration Act of 1965 put an end to restrictive immigration quotas, allowing more people to immigrate to the U.S. from across Asia. At the end of the Vietnam War in 1975, numerous Southeast Asian refugees resettled in Oakland. The library’s commitment to diversity int its values and programs became exceedingly important as Asian America grew more ethnically, economically, and generationally diverse.

Concurrent with library activism in the Bay Area, the Asian Community Library envisioned itself as an accessible, inclusive, and intergenerational community center with language and multiethnic representation as core values. Books, movies, music, and newspapers in multiple Asian languages filled shelves for the education, enjoyment, and cultural invigoration of library patrons. Today, it continues to be a meeting spot, reference service, and cultural resource, with a staff and collection that strive to reflect the community they serve.

— Kelly Wong

Kelly Wong (Cal ’20) double majored in Urban Studies and Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies. She is interested in the rich and diverse histories of the Bay Area.

Kelly Wong (Cal ’20) double majored in Urban Studies and Asian American and Asian Diaspora Studies. She is interested in the rich and diverse histories of the Bay Area.

Acknowledgements

Kelly Wong wishes to thank Judy Yung and William Sato for sharing their experiences with the Asian Community Library, Suzanne Lo and Roy Chan for providing resources, and the professors of the “East Bay Revolution” class for their inspiring passion for revolution. The author encourages everyone to visit the Asian Branch Library and learn more about its community.

Additional Resources

Asian American Organizations Files, Asian Branch of Oakland Public Library. Oakland, CA.

Roy Chan, “Oakland Chinatown Oral History Project”.

Curtis Choy, Al Robles, and Emiko Omori, The Fall of the I-Hotel (Chonk Moonhunter Productions, 2005).

Karen L. Ishizuka, Serve the People: Making Asian America in the Long Sixties (New York: Verso, 2019).

Clement Lai, “Saving Japantown, Serving the People: The Scalar Politics of the Asian American Movement,” Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 31:3 (June 2013), 467–84.

Yen Le Espiritu, Asian American Panethnicity (Los Angeles: University of California/Asian American Studies Center, 1996).

Dana Y. Nagano, “An Interlocking Panethnicity: The Negotiation of Multiple Identities among Asian American Social Movement Leaders,” Sociological Perspectives, Dec. 2013, 575–586.

Judy Yung, the librarian of the Asian Community Library at its founding, in 1976