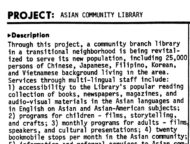

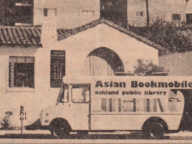

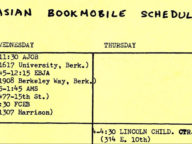

In this article, written the year after the opening of the Asian Community Library (ACL), Judy Yung explained how the ACL worked and how it aimed to grow. The article documents the programs and services of the ACL in its initial year of operation, and provides updates on the library and its funding for its third and fourth year.

In addition to collecting reading material, the library also collected audiovisual materials for recreational and educational groups. Popular records and cassettes constituted 27% of the branch circulation, pointing to how ACL users aimed to access their own culture through items that might be unavailable in American stores.

Materials were chosen to reflect the interests of the community, but also to accurately represent Asians and Asian Americans. Notably, when determining films to purchase, library staff found that “educational films on Asia geared for classroom use are most disappointing. The majority of these films are out of date, unimaginative, condescending, or inaccurate.”

This critique of standard “educational films” suggests the difference that the Asian American Movement made, in reshaping the relationship between Asian-Americans and the peoples of countries such as Vietnam, China, and the Philippines. Prior to the Asian American Movement, Asians and Asian Americans were labeled “oriental”, which turned them into exoticized ‘others’. In addition, Asians were often portrayed in Hollywood movies as villains.

The library staff selection previewed all films and content before circulation in order to provide relevant and representative works that patrons could learn from or relate to. There was an intentional goal to make the library a space where Asian-Americans could learn their history, free from the lack of imagination or condescension that characterized many conventional treatments of Asian and Asian-American history, and where they could foster a better-informed sense of their own identity.