In its first issue, The Flatlands profiled Mark Comfort, who, for several years in the 1960s, was one of Oakland’s most celebrated and effective civil rights activists.

An early contributor and central figure to The Flatlands, Comfort became known for his running court battles with the Oakland Police Department and Joseph Knowland’s arch-conservative Oakland Tribune.

Comfort was born in Oklahoma City in 1934, moving to his grandmother’s West Oakland home in 1941. In this profile, he described the impact that racism and police brutality had on his political awakening. Attending a Halloween party near Arroyo Viejo Park in East Oakland, Comfort and friends were accosted by a group of racists. The ensuing brawl led to Comfort’s arrest; charged with “deadly assault with a weapon in a race riot,” he faced up to 15 years in prison. Comfort was eventually sentenced to only a year in San Quentin but his arrest and the demonstrations that followed it, in his words, “hipped [him] to old man Knowland and the power structure.”

Following his release, Comfort spent a short time in Southern California, before returning to the Bay Area for a union job in San Francisco. His connections to the Bay Area labor movement led him in 1962 to take a position with the East Bay Communist organizer Roscoe Proctor’s Youth for Jobs (YFJ), a group that fought youth unemployment and economic underinvestment in Oakland and Berkeley’s black neighborhoods. Following his stint with YFJ, he became a key player in the Ad Hoc Committee to End Discrimination, a coalition of civil rights organizers who fought employment discrimination in the Bay Area.

The Committee held pickets at the Sheraton Hotel in San Francisco, dealerships on Oakland’s Auto Row, and Mel’s Drive In locations throughout the Bay Area. Additionally, it publicized a boycott list of Bay Area businesses which refused to hire black employees. Taking the fight to “old man Knowland,” Comfort helped to organize a boycott and demonstrations against the Tribune, culminating with his arrest by Oakland police in 1964 for taking part in a blockade of the Tribune building.

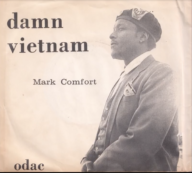

Presaging the later “Free Huey” campaign, “Free Mark Comfort” became a rallying cry for Bay Area activists; a 45 single featuring his defiant anti-war anthem “Damn Vietnam” (links: here and here) was pressed and sold widely to assist with his defense. The lengthy court battle did nothing to dampen Comfort’s spirit; his arrest had solidified for him the belief that only direct confrontation with the powers-that-be could bring about political change. After serving a 30-day jail sentence, he formed the Oakland Direct Action Committee (ODAC) in 1965. As he did with YFJ, Comfort used ODAC to mobilize Oakland youth, organizing demonstrations and school walkouts to protest acts of police brutality in their communities.

Presaging the later “Free Huey” campaign, “Free Mark Comfort” became a rallying cry for Bay Area activists; a 45 single featuring his defiant anti-war anthem “Damn Vietnam” (links: here and here) was pressed and sold widely to assist with his defense. The lengthy court battle did nothing to dampen Comfort’s spirit; his arrest had solidified for him the belief that only direct confrontation with the powers-that-be could bring about political change. After serving a 30-day jail sentence, he formed the Oakland Direct Action Committee (ODAC) in 1965. As he did with YFJ, Comfort used ODAC to mobilize Oakland youth, organizing demonstrations and school walkouts to protest acts of police brutality in their communities.

***

In the spring of 1966—after the publication of this profile in The Flatlands—Comfort and other members of ODAC traveled to Lowndes County, Alabama, to assist SNCC and local black organizers with security measures. SNCC leader Stokely Carmichael had chosen Lowndes County as a test site for a voter registration campaign targeting black voters, and the threat of white supremacist political violence had convinced him of the necessity of armed self-defense. The experience of the Lowndes campaign was heavily influential on Carmichael’s later formulation of Black Power, as he rejected the centrality of passive resistance as a protest tactic and advocated a militant, confrontational demand from the white power structure for black equality and autonomy.

Black Power was not the only significant consequence of the Lowndes campaign. Given the illiteracy of many Alabama voters, black and white alike, political campaigns relied heavily upon easily-recognized logos. While the white campaign used the image of a fighting cock, SNCC famously chose a coiled black panther for its campaign’s logo, and black organizations across the nation began to adopt it as a symbol of Black Power. Comfort himself was much taken with the symbol. In Flatlands photographs following his return from Lowndes, he can frequently be seen sporting a black beret with a black panther pin prominently displayed.

***

The work of Gloria Comfort, herself the daughter of Communist labor activists, was often less visible than her husband’s, but it often paralleled and enhanced her husband’s efforts. The two jointly organized a concerned parents’ group, the Parents’ Association for Better Education to advocate for free lunch programs and educational equity. This organization evolved into the Ad Hoc Committee for Quality Education, which organized a three-day walkout attended by thousands of students in Oakland schools, while sponsoring “freedom schools” for striking students. She was also instrumental in organizing the Lockwood Improvement League, a neighborhood organization of public housing tenants; was a founding staff member of the Oakland Peace Center spearheaded by veteran Californians for Liberal Representation (CLR) organizer Jerry Rothstein; and was a steady contributor to The Flatlands, serving on its editorial board.

***

Mark was a frequent speaker at anti-war demonstrations and Black Power symposiums, but his most consequential contribution to movement history came following the April 1967 shooting of Denzil Dowell by Richmond police. After attending a community vigil in Dowell’s North Richmond neighborhood, Comfort drove to the Black Panther Party office in North Oakland to inform Party leaders Huey Newton and Bobby Seale of the event. Dowell’s murder became the impetus for the Party’s subsequent armed demonstration in Sacramento, an event that would catapult them to worldwide fame.