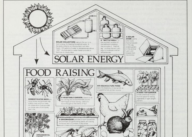

Set against the backdrop of an increasingly consumptive America, the Integral Urban House was a revolutionary project seeking to challenge dominant patterns of energy use and food production.

“One cannot escape the statistic that America, with 6% of the world’s population, uses 35% of the world’s energy . . . Our privileged status can only be maintained at the expense of the rest of the peoples of the world.” — Sim Van der Ryn, UC Berkeley architect and founder of the Farallones Institute

This proposal from Sim Van der Ryn outlines current unsustainable practices and energy consumption patterns in the United States. Increasing awareness of global resource patterns and exploitation of colonized people lay the groundwork for a need to reduce consumption. It urges the reader to consider residential heating and cooling systems, as well as waste management systems, as fundamentally flawed.

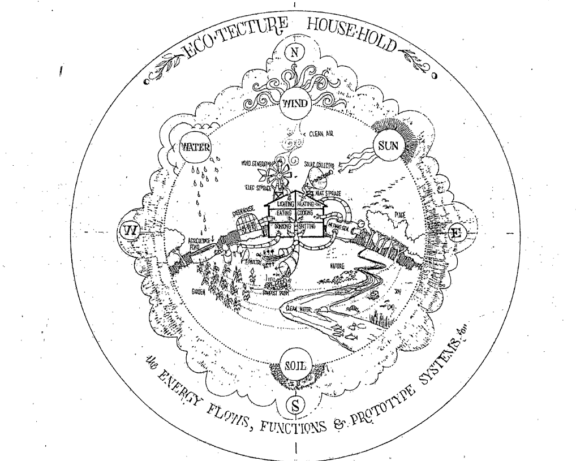

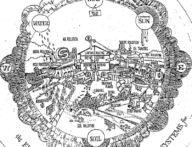

At the end of the post, the author uses the symbol of a mandala, a South Asian geometric configuration of images and spirituality (seen above), to visualize and map out the energy flows entering and exiting a household. At the time, an affiliation for Eastern philosophy popularized imagery and religious beliefs from South and East Asia. Mandalas were used to represent wholeness and organization within systems, but New Age movements have appropriated them to represent the totality of the universe and the cosmos. Here, Van der Ryn contrasts the linear “techno-fantacy” model of the home with the closed “eco-fantacy” habitat system.

This close-up of the ‘technofantacy’ house shows a busy, complex mass of pollution and waste, centered around the single-family American home. In the home, there are the essential features like “lighting, heating, eating, cooking, drinking, and shitting.”One can see the cardinal directions on all four sides, as well as the basic natural inputs of water, sun, soil, and wind. It comically shows wind as “not in use”, representing how little influence it has on this existing system. The entire mandala is also surrounded by a dark haze of clouds, most likely to represent dangerous air pollution and smoke. It gives the entire image a much darker feel. Around the house are unpleasant outputs like water pollution, soil pollution, oil tankers, and air pollution; this is to demonstrate how reliant modern urban society is upon these engineered products out of tune with nature. It depicts the ‘technofantacy’ house as a dirty dystopia, but it was (and continues to be) the gross reality that many Americans live in, buying processed food from the supermarket and reliant on fossil fuel-generated energy.

In contrast, the ‘ecofantacy’ house above tells a quite different story about how nature influences the house itself. Water, wind, sun, and soil are active agents in influencing the house’s production. The clouds around the mandala are white and the whole image is less crowded than the ‘technofantacy’ house. Features like a solar collector, a greenhouse, a methane generator, and electricity storage are all connected together by tubes, demonstrating this interconnectivity not present in the ‘technofantacy’ house. Furthermore, abstract concepts like joy, nature, and peace are found in the forest, stream, and sky. Van der Ryn shows that when one lives closer to nature, other ideas like peace and joy can flourish too, making the environment and experience better.