In his essay in the anthology Revolting Librarians, Sanford Berman called for libraries to act truly in accordance with their Bill of Rights and “stock material covering all possible political and other viewpoints”.

He lambasted libraries for timid collections that contained few countercultural and radical periodicals, and enjoined his readers to demand that their libraries collect the radical press, especially those publications coming out of the Third World liberation movements: “Blacks who find nothing live in their local library collections should insist on subs to soulful, uppity periodicals like the Black Panther, Black World, Journal of Black Poetry… Chicanos and Puertoriquenos know what fine stuff like Con Safos, Regeneración, El Malcriado, Grito del Norte, Palante, and La Raz has been tumbling out of the barrios but not reaching the library racks. Likewise, the Asian-Americans’ Gidra, Getting Together, and Hawaiian Pono Journal are wonderfully rare in most libraries. Ditto the wealth of Amerindian publications, from Rainbowpeople to the Indian Historian. It would no less amaze gays to spot Gay Sunshine or Come Out! in a library mag collection than it would startle a feminist to sight Everywoman, Aphra, Ladder, or the excellent Baltimore quarterly, Women.”

Inspired by the Third World, feminist, and gay liberation movements of the 1960s and early 1970s, Berman argued that a library’s collection needed to feature the voices of the marginalized. Marginalized communities were publishing their own magazines, rewriting history, and redefining their identities, and librarians had to be attuned to the literature of these movements to promote learning and foster self-determination within the communities they served.

Berman’s essay underlined that radical librarians might face serious consequences for following his advice: he mentioned that his engagé colleagues had been disciplined or lost their jobs for trying to stock publications like the Village Voice, Evergreen Review, and The Los Angeles Free Press. But it was crucial to take up the fight. The alternative was to leave the library as an institution in the hands of society’s conservative forces.

***

Berman’s essay appeared in Revolting Librarians, a key anthology that emerged from the radical librarian movement of the late-’60s and early-’70s. The anthology contained over 30 essays, poems, and stories, ranging from a story about creating an informal library for migrant workers to critiques of the idea of “professionalism” within library science.

Notably, the radical librarian movement was spearheaded by feminist librarians. In her editor’s introduction to Revolting Librarians, Celeste West put a twist on the idea that “the personal is political,” suggesting that radical librarians refused to think that there was any “conflict of interest” between their lives and their work. Instead, they sought to infuse their “hopes, conflicts, [and] growth” into that work. That meant, as West suggested, that they no longer wished to work in “Book of the Month Club Libraries run for the leisure of Mr. and Mrs. Mid-Cult and the profit of the publishing plutocracy.” (West also founded magazines such as Synergy, in which librarians engaged in addressing bias and systemic change, and Booklegger Magazine, a feminist library journal.)

The larger anthology conveys how the social movements of the 1960s reshaped public institutions such as museums and libraries, prompting those who worked at these institutions to reconsider how they served the larger public. Librarians, the contributors to Revolting Librarians argued, needed to be more self-conscious about their work if they wished truly to serve a more inclusive public. They recognized that librarians were not unbiased agents, but rather people with their own ideologies, self-conceptions, and convictions. They recognized, too, that the material they carried could perpetuate the power structure of their day. Libraries had the duty, then, to present multiple perspectives in their collections, through material from a truly diverse range of authors.

As part of a government-funded institution, public librarians were in a position of power that could be leveraged for historically oppressed communities whose stories had been ignored, rendered invisible, or erased from public knowledge.

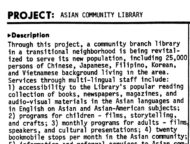

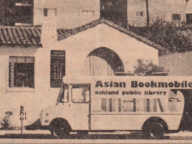

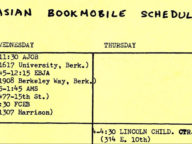

With its call for librarians to be accountable to their communities, Revolting Librarians resonates with the story of the Asian Community Library. Three years after its publication, the Asian Community Library’s Judy Yung powerfully took up that call.

(To access the full anthology Revolting Librarians, click here.)