The Black Panthers’ Education Revolution

“If we want to change things the best way to begin is to educate our children.”

— Ericka Huggins

In schools, newspapers, and popular culture, the Black Panthers are often presented as armed Black radicals.

Images of the 65 community survival programs that the Panthers created in Oakland—among them a free clinic, vibrant community learning center, and busing for seniors program—are less prevalent. One of the most impactful and long-lasting of these programs was the Oakland Community School (OCS), an elementary school in the Fruitvale neighborhood of East Oakland.

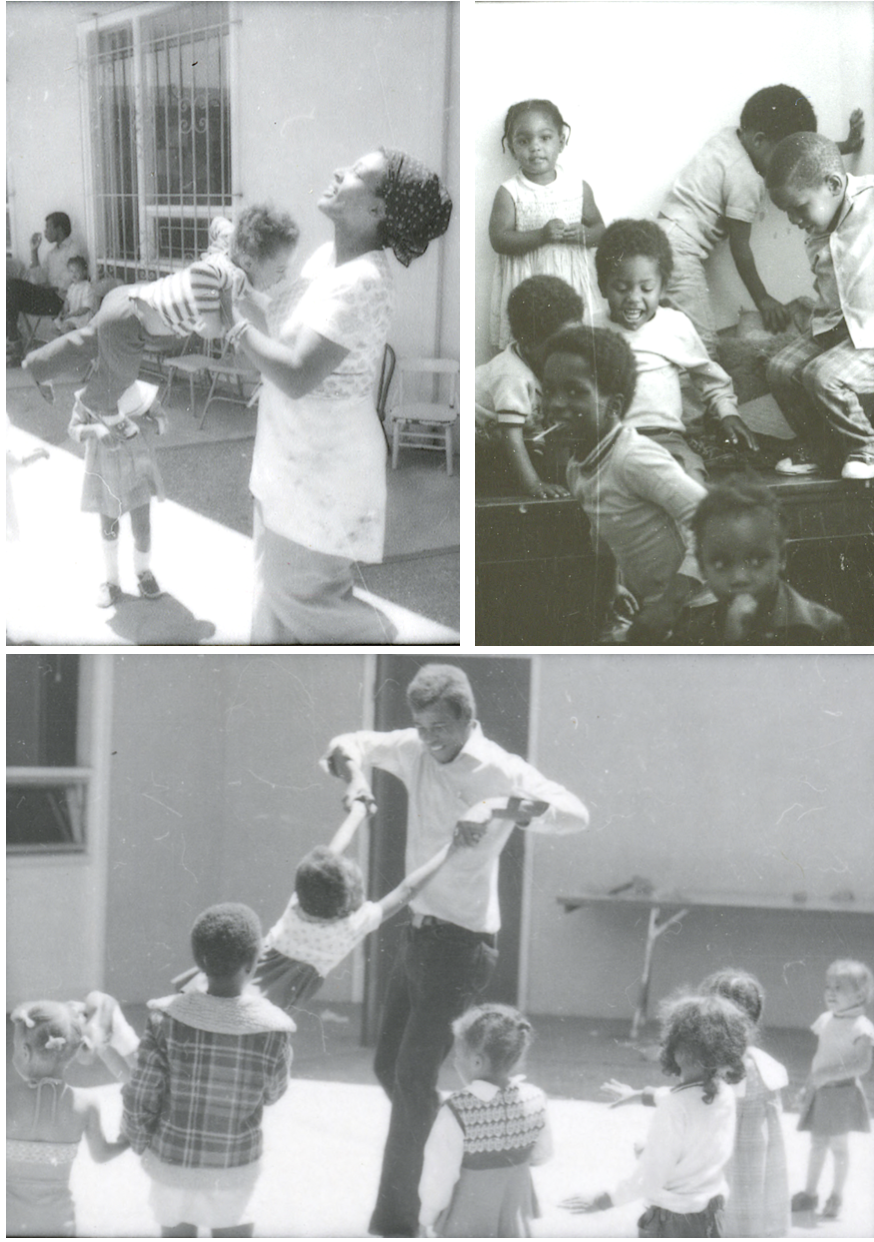

At the OCS, students were nourished in body and mind. They were provided with three meals a day, encouraged by teachers who were fellow people of color, and taught to become critical thinkers who were engaged with their community and its history.

The materials we have gathered provide valuable insight into the evolution of the Panthers’ schools, from the Children’s House into the Intercommunal Youth Institute and later into the Oakland Community School.

When people look back at Panther schools and see how they changed over time, some critics say that Oakland Community School diluted the revolutionary, radical spirit of the Children’s House and the Intercommunal Youth Institute.

This collection of documents tells a different story. Though Panther ideology was not in the foreground at the Oakland Community School, the school provided predominantly Black, low-income students — students who may have otherwise have been marginalized and harmed by the public school system — with care, healthy food, and emotional support, while also sparking their curiosity and critical thinking. This in itself was a radical act.

The Roots of the Black Panthers’ Education Revolution

The BPP’s educational projects — the Oakland Community School and before it, the Children’s House and the Intercommunal Youth Institute — did not appear out of thin air. Rather, they were born out of a long history, within the Black community, of using education as a tool for liberation.

This history included schools that served enslaved Africans in the 18th and 19th centuries; labor schools during the early 20th century; Citizenship Schools in the 1950s; and Freedom Schools run in the mid-1960s by the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, which aimed to prepare African Americans to be politically active in the Civil Rights era.

African American women have historically led efforts for revolutionary education. Ericka Huggins, the director of OCS, sees the activism of BPP women as continuing a “tradition of radical educators” in the African American freedom struggle — a tradition that encompasses grassroots leaders from Sojourner Truth and Harriet Tubman to Civil Rights organizers Ella Baker and Fannie Lou Hamer.

The Black Panther Party and Education: A Brief Overview

The Oakland Community School arose out of a need articulated in the fifth point of the Panthers’ original Ten-Point Platform, written by Huey Newton and Bobby Seale in 1966: “We believe in an educational system that will give to our people a knowledge of the self. If you do not have knowledge of yourself and your position in the society and in the world, then you will have little chance to know anything else.”

In a short TV segment on the OCS, Newton explained (in an interview with a young OCS student) how, during his time in Oakland public school system as a child, he was poorly served in all ways by his schools — forced to learn a whitewashed version of history, punished by teachers for his curiosity, and deprived of access to nutritious food.

The Children’s House, the Intercommunal Youth Institute, and the Oakland Community School sought to remedy these deficiencies of the surrounding public school system and offer a positive alternative. As Ericka Huggins underlines in her oral history, the OCS sought to give students the opportunity to gain a knowledge of themselves, their history, and their place in society through student-centered education, critical thinking, and real world learning.

It represented an evolution, or departure of sorts, from the Panthers’ earlier schools — the Children’s House and the Intercommunal Youth institute, where the children at the schools were the children of Party members and were asked to learn about Panther ideology and wear black berets and uniforms; they were learning, in every sense, to become future Panther leaders. The OCS built upon the curriculum and approach of these earlier schools, while also taking in a wider range of students and expanding its curriculum.

Scenes from the Oakland Community School from the same TV program contrast sharply with the experience of Oakland public schools that Newton detailed. In one classroom, young students learn about settler-colonialism and Native American history. Curiosity and critical thinking are highly encouraged, not punished. And throughout the school day, students are fed three nutritious meals by teachers who care for them.

The curriculum and approach of OCS may no longer have centered on the direct inculcation of Panther ideology, but the school realized, in perhaps unexpected ways, the fifth point of the Panther’s original Ten-Point Program: the liberation of “Black and other oppressed people” through alternative forms of education.

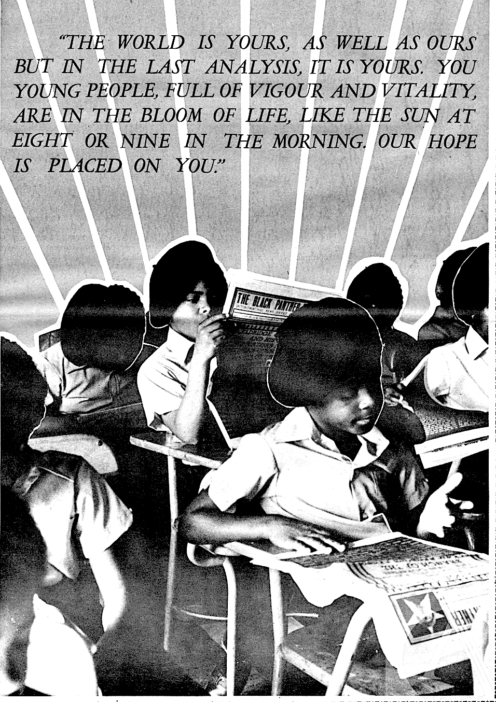

“Youth Make the Revolution”: The Children’s House and the Intercommunal Youth Institute

Though Black Panther Party schools changed over time, innovative, revolutionary education was a constant. The Party not only educated Black youth and prepared them to survive in the world, but also provided a model of what a transformational education could look like. Children’s Houses initially served as the setting for educational efforts that focused on revolutionary history and practice. Party members who were off organizing, incarcerated, or feared that their political activity would have repercussions for family members enrolled in public schools placed their children in communal residences where they attended class, ate, and grew up together.

In January 1971, the party opened the Huey P Newton Youth Institute, soon known as the Samuel L Napier Intercommunal Youth Institute (IYI). The Panthers regarded education as a key precursor to liberation, but also a tool of the oppressor when controlled by those outside of the Black community. The IYI provided an alternative to public schools in which the standard curriculum reflected from a largely white perspective, and in which many Black students experienced discriminatory treatment and faced low teacher expectations. By recognizing students’ potential, treating them with respect, and giving them a voice in the curriculum, the IYI provided the independent agency and environment of kindness that so many public schools lacked. The IYI also modelled the importance of community. Students learned, lived, and ate together. With basic needs met, students were more equipped to engage in classroom activities. The IYI served as a template not only for educational institutions but also for a more just and communal society.

The Youth Institute curriculum, which included math, language arts, science, group art, political education, and field trips, cultivated a revolutionary identity within its student body. Students wore panther uniforms, wrote letters to jailed party members, sang the Black National Anthem, passed out flyers, and learned Party history. Many felt a sense of pride associated with their identity as young revolutionaries. In an Intercommunal News Service interview , students discussed their newfound knowledge of the Party and the importance of education. Many had struggled in public schools where they acted out, confronted teachers, or felt unchallenged intellectually. At the IYI, with teachers whom they considered comrades and with a curriculum relevant to their lives, the same students flourished.

Classes embodied two main principles. First, subject matter was not presented in a one-sided manner, but rather was to be analyzed from multiple perspectives. Rather than teaching the students what to believe, the school aimed to create critical thinkers who could analyze information and decide for themselves. The second principle was the importance of experiencing what one wanted to understand and change. Experiential learning, including field trips and letter writing, was fundamental to the curriculum, allowing students to apply what they learned in class to their lived reality.

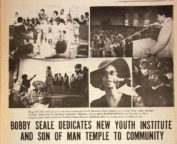

In its first few years, the IYI grew and was relocated to a larger space. In 1975, its name changed to the Oakland Community School (OCS), signaling a shift from Party affiliation to the general community. Non-Party students could attend and the Panther uniform was no longer mandatory. By expanding beyond the children of Party members, the school lost its overtly ideological appearance. But the school’s growth also meant that more Oakland children would receive a high quality education and break from a cycle of oppression. Success and expansion proved that the Panther’s teaching methods were sustainable and effective.

“I Want to Help My People Be Free”: Education as a Tool for Liberation at Oakland Community School

Though Oakland Community School did not teach Panther ideology, the school’s focus on critical thinking, experiential learning, respect for students, and care for the whole child served the Party’s liberatory goals.

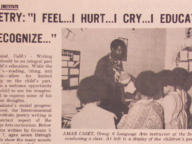

The school’s culture stressed critical thinking. Rodney Gillead, a former teacher, noted that many OCS teachers at OCS were influenced by “Pedagogy of the Oppressed,” Paulo Freire’s manifesto on education based upon culturally relevant, critical thinking as the key to liberation. Gilead recounted that when a student or teacher made a statement, they would often be asked: “Did you investigate?” The question emphasized the importance of backing up arguments with verifiable information.

Critical thinking permeated the curriculum at all levels. A rough draft of the school’s critical thinking program includes curricular concepts including “common thinking flaws” and philosophical inquiry. An article from the Black Panther Intercommunal News Service described the OCS American history curriculum as nurturing a more accurate and honest understanding of history by presenting students with information and encouraging them to draw their own conclusions.

Reflecting the school’s motto “The World is a Child’s Classroom,” numerous opportunities to learn through real world experiences were afforded to OCS students. Field trips included visits to San Quentin prison, the Black Engineers Conference, and the Afro-American Cultural and Historical Society in San Francisco. OCS students engaged with history and current events through several plays that they created and performed. The world also came to the School: Maya Angelou, Rosa Parks, Cesar Chavez, and James Baldwin, among others, made memorable visits.

OCS students had an important say in how the school was run. The Youth Committee weighed in on decisions regarding curriculum and activities, helped fundraise for the school, and ran a radio station. The Justice Board, which was made up of representatives from each class, was in charge of meting out disciplinary actions for students who broke significant rules. Rodney Gillead said that this lessened the hierarchical power dynamic between students and teachers, and was more effective because students held each other accountable.

The Oakland Community School sought to clear away obstacles to learning by supporting students’ physical, psychological, emotional, and spiritual needs. Huggins states “It’s impossible for a child to think about Language Arts if he or she has no food at home. It’s impossible for a child to think about Mathematics if she doesn’t know whether she’ll be able to get to school in the morning because she doesn’t have a pair of shoes. If a child is seeing constant argument or struggle, it’s impossible to think about what makes flowers grow and why there are stars and the sun and the moon.”

The OCS became part of the larger community. Parents and locals often volunteered at the school, which was closely connected to the Community Learning Center. Students participated in Black Panther protests and Party events, and advocated for other children in the community. OCS staff knew that difficulties in a child’s home life have a major impact on how they show up at school, so Huggins and her colleagues provided counseling to students and families.When she noticed the ravenous hunger of students who lacked food at home, the school began serving lunch and dinner in addition to breakfast. After lunch, everyone in the school meditated together. “A blanket of the silence would fall over the multi-purpose room when we did that and then we would get up and go on with our day. It was so beautiful.”

Mainstream Success: Compromising Ideology or Gaming the System?

In 1977, the California state legislature awarded the OCS a commendation in recognition of “the highest level of scholastic achievement in elementary education and for having concretely defied the myth of the uneducable child,” a testament to the school’s success and impact given the fraught relationship between the party and the government. Small class sizes, placing students according to their ability, free meals, and medical care contributed to the schools exceptionally high achievement scores and a waitlist of over 400 people. Test scores proved that Oakland Community School’s methods were effective and highlighted reforms needed in public schools. In 1978, students of the OCS scored 1 to 2 grades beyond their age level on the comprehensive test of basic schools.

Mainstream news sources, including Jet, a nationally distributed African American news magazine, lauded the school’s achievements. In a 1976 interview in Jet, Ericka Huggins distanced the OCS from previous Panther schools and their radical rhetoric. A more traditional curriculum did not represent a shift in Party goals, she insisted: “We are the same people we always were, we want a new order of things in this society and in the world. But we realize that if ‘A’ is oppression and ‘Z’ is freedom, you can’t jump from A to Z. If we want to change things the best way to begin is to educate our children.”

According to Huggins, the OCS proved that poor Black children were “educable,” contrary to what many public school teachers seemed to believe. The OCS, while abandoning aspects of the revolution-oriented curriculum of the earlier Intercommunal Youth Institute, realized one of its founding goals: the creation of a model school. Oakland public school teachers and city council members acknowledged the success of the OCS in instituting reforms that long deemed necessary by local teachers.

The other founding goal of the IYI, of creating a model school, was also achieved. The success of the Oakland Community School challenges how the story of the Black Panther Party is often told. Education historian Daniel Perlstein has argued that Panther-sponsored schools became more mainstream over time and thus lost touch with the Party’s original revolutionary aspirations, embracing electoral reforms and assimilation to the system rather than challenging it.

Perlstein misses, however, how the recognition the OCS achieved helped expose the failure of public schools, and how the OCS, in modeling a communal form of education, was revolutionary in and of itself. The goal behind the founding the IYI was never to grow party membership. It was, as written in 1971, “educate to liberate.” Shifting away from party rhetoric allowed for a larger student body and positive national recognition that a more explicitly radical Panther school would not have received. Though less ideologically pure, the OCS was able to have a larger impact on its students and the community.

— Hannah Bahls and Dewi Zarni

Dewi Zarni (Cal ’21) is an American Studies major concentrating in Migration. Raised in the East Bay, she loved learning more about the area’s revolutionary history and its lasting impact.

Dewi Zarni (Cal ’21) is an American Studies major concentrating in Migration. Raised in the East Bay, she loved learning more about the area’s revolutionary history and its lasting impact.

Acknowledgements

Additional Resources

This project on the Oakland Community School is indebted to recent scholarship that draws out, more generally, the contributions of women within the Black Panther Party, as well as to specific work on the Oakland Community School and the Panthers’ educational programs.

Elaine Brown, A Taste of Power: A Black Woman’s Story (New York: Random House, 1992).

Ashley D. Farmer, Remaking Black Power: How Black Women Transformed an Era (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Ericka Huggins, “An Oral History with Ericka Huggins” (interviews conducted by Fiona Thompson in 2007), Oral History Center, Bancroft Library, UC Berkeley, 2010.

Ericka Huggins and Angela D. LeBlanc-Earnest, “Revolutionary Women, Revolutionary Education: The Black Panther Party’s Oakland Community School,” in Dayo Gore, Jeanne Theoharis, and Komozi Woodard, eds., Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle (New York: NYU Press, 2009).

Daniel Perlstein, “Minds Stayed on Freedom: Politics and Pedagogy in the African-American Freedom Struggle,” American Educational Research Journal 39:2 (Summer 2002), 249-277.

Robyn C. Spencer, The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

Robyn C. Spencer, “Communalism and the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California,” West of Eden: Communes and Utopia in Northern California (Oakland: PM Press, 2012).

Radical joy: scenes from the Oakland Community School (photographs by Bob Fitch)