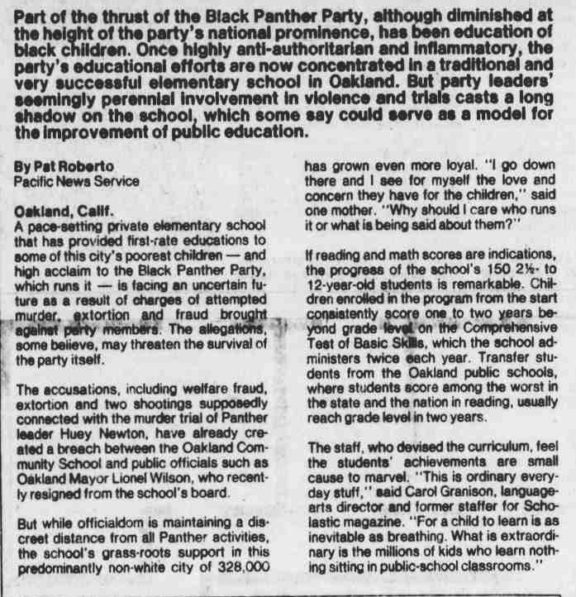

In this 1977 article from the Pacific News Service, a non-profit alternative news outlet, journalist Pat Roberto contrasts the criminal charges brought against some party factions with the growing success of the “pace-setting” Oakland Community School.

According to Roberto, the Panther’s education efforts had shifted over time from “anti-authoritarian and inflammatory” to the more traditional and esteemed pedagogy of the OCS. Roberto sketches the negative publicity surrounding the Panthers, who were accused of welfare fraud, murder, and extortion. Oakland Mayor Lionel Wilson had resigned from the OCS Board, as the school had been accused of re-directing funds appropriated to OCS to pay rent for Party members.

Roberto contrasts the recent shadow cast over the Black Panther Party with the widely-held and enthusiastic community support for the school. Students who transferred from or were kicked out of OUSD schools showed amazing improvements, thanks to class sizes two to four times smaller than those in public schools; before- and after-school child care; three hot meals a day; medical care; and overnight lodging when needed—all at an affordable or no cost.

While the frame of Roberto’s article suggests that the OCS may have represented a de-radicalization of the Panthers (an argument that would later be seconded by the education historian Daniel Perlstein), there are alternative voices within it, offering a counterargument. Ericka Huggins, the school’s director, pushed back against the notion that Panther philosophy had become less radical, and saw education as a necessary step in the struggle for liberation. The simple existence of the school — which modeled a less capitalist future, where there was investment in free public education and integration of school and community—was radical in and of itself, she implied.

According to curriculum coordinator Dr. Bill Moore, the awards and government grants provided to the school represented not an embrace of the system, but an understanding of how to work within it to achieve their vision. While most school faculty were party members, unaffiliated staff and parents did not see the school as instilling an ideology, but rather teaching children to make their own decisions.

While most school faculty were party members, unaffiliated staff and parents did not see the school as instilling an ideology, but rather teaching children to make their own decisions.

The success of the OCS highlighted the failures of public schools, which had long blamed students for their own struggles in school, for example, relegating struggling students to special needs classes. The school’s rejection of these ideas was emblematic of their ideology – they understood that the system, deeply rooted in white supremacy and capitalism, was to blame for the struggles that Black Americans faced and continue to face. The school further fought the individualistic capitalist mindset by teaching the importance of helping others above financial gain or fame.