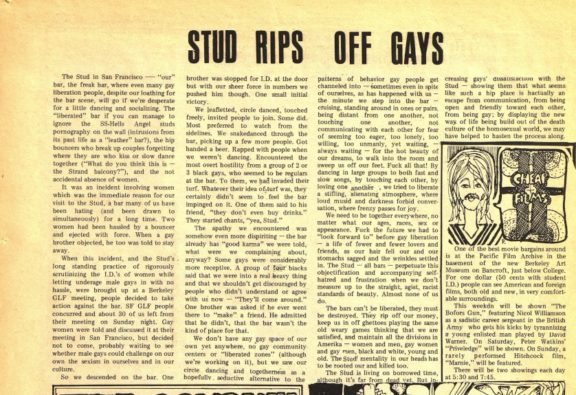

To many within the Gay Liberation movement, gay bars not only symbolized the “Gay Establishment,” but also actively discrimated against and policed more radical individuals and groups. Many gay bars in San Fransisco required multiple forms of ID for Black people, barred women from entering without a man, and prohibited touching.

An article from The Berkeley Tribe in March 1971 summarizes the complaints against gay bars in the Bay Area. First, is there violent exclusion of women, the Stud would both kick women out of the bars and not let them in. The Stud, along with other gay bars, also discriminately ID’d women.

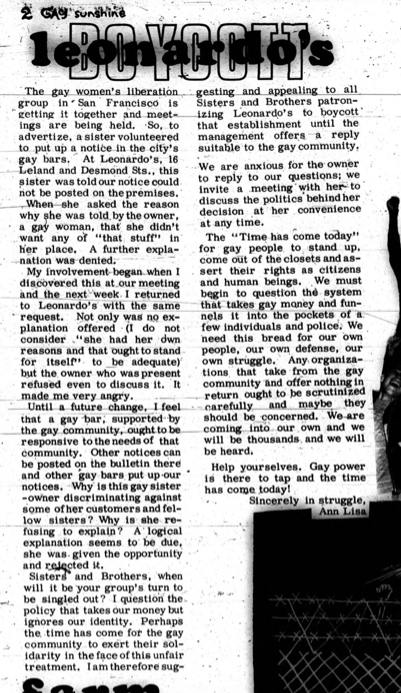

There were multiple altercations with gay bars in the San Francisco Bay Area in the fall of 1970. The first was with Leonarda’s a gay bar, in San Francisco, whose owner, a gay woman, prohibited a member of the Gay Women’s Liberation from posting flyers for GWL meetings. The Gay Women’s Liberation group responded with a call to boycott Leonarda’s, demanding changes to the way gay bars operated.

We must begin to question the system that takes the gay money and funnels it into the pockets of a few individuals and police. We need this bread for our own people, our own defense, our own struggle. Any organizations that take from the gay community and offer nothing in return ought to be scrutinized carefully and maybe they should be concerned. (1)

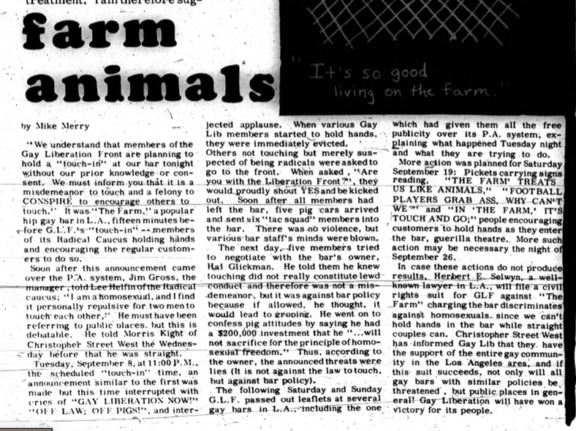

Another claim against gay bars was their practice of prohibiting touching inside of the bar, a form of self-policing by bar owners to protect themselves from police raids. An article from Gay Sunshine, recounts a protest by the Los Angeles Gay Liberation Front, called a “touch-in” at a gay bar called “The Farm”. On September 8, 1970, members of the L.A. GLF held hands inside of the bar, and were subsequently thrown out by the owners. The owner had threatened the protesters with arrest, making false claims that touching was a misdemeanor and calling the police.

The next day five members tried to negotiate with the bar’ owner, Hal Glickman. He told them he knew touching did not really constitute lewd conduct and therefore was not a misdemeanor, but it was against bar policy because if allowed, he thought, it would lead to groping. He went on to confess pig attitudes by saying he had a $200,000 investment that he “…will not sacrifice for the principle of homosexual freedom.” Thus, according to the owner, the announced threats were lied (It is not against the law to touch, but against bar policy). (2)

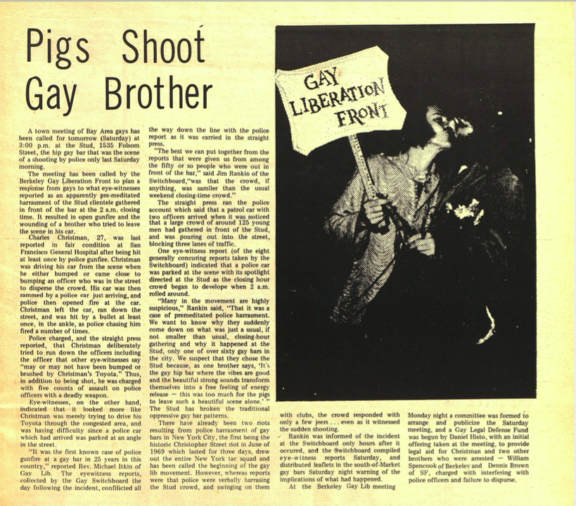

In addition to policing touching within the bars, Gay Liberation critiqued gay bars for cooperating with the police and not defending the gay community. “The Stud,” a gay bar in the SOMA district, came under repeat attention in 1970 for harassing the gay community and was the site of a police shooting of a gay man on Saturday December 12, 1970. Charles Christman was shot by police outside of the Stud as it was closing, after they open fired into the crowd, leading many in the Gay Liberation to believe that the police were waiting for the bar to close so they could harass the people leaving. Christman recovered, but he was charged with assault after a police car rammed his car.

The gay community began organizing to collect witnesses, using the Gay Switchboard in Berkeley to funnel information in defense of Christman. After members of the Gay Switchboard learned what happened, they created leaflets with information to pass out to the gay community, particularly in the gay bars in the South of Market district. That Monday, Berkeley Gay Liberation organized the “Gay Legal Defense Fund,” to help with legal defense for Christman, as well as other individuals that were arrested that night at the Stud. On Saturday December 19, the Berkeley and San Francisco Gay Liberation groups came together at the Stud to organize witness statements.

Gay bars symbolized the Gay Liberationist’s formulations of the “Gay Ghettos,” a concept reworked by the Gay liberationists to theorize the spaces, ideas, and politics that chacterized the “Gay Establishment,” comprised of homophile groups like SIR, The Daughters of Bilitis, and the Tavern Guild. The police’s main tactic for suppressing gay political action was harassing gay bars and the indivdiuals coming in and out. However, the Gay Liberationists viewed the bar owners as collaborating with the police to harass gay patrons. They also exploited the hyper-policing to enforce their own anti-touching rules, making gay bars unsafe. Gay Liberationists used an anti-capitalist framework to critique the bars, as they took money from the gay community, but didn’t give any radical support back, an exploitative model of business. Additionally, they saw the gay bars as re-enforcing racism and sexism by discriminating against Black people and People of Color, lesbians, Trans folks, and sex workers.

The Stud — all bars — perpetuate this objectification and accompanying self-hatred and frustration when we don’t measure up to the straight, ageist, racist standards of beauty. Almost none of us do. The bars can’t be liberated, they must be destroyed. They rip off our money, keep us in off ghettoes playing the same old weary games thinking that we are satisfied, and maintain all the divisions in Amerika — women and men, gay women and gay men, black and white, young and old. The Stud! mentality in our heads has to be rooted out and killed too. (3)

This critique of gay bars was met with pushback by members of the gay community. To some, protesting and critiquing the one public space for gay people was counterproductive.

Nick Benton has made slanderous generalizations in his attack on gay bar patrons. I occasionally visit gay bars and I go not because I am alienated, straight or hung-up. I go because I am alone and seek companionship. (4)

Particularly for many middle-class, white gay men, the bars didn’t feel exclusive, so they felt no need to change them. However, a growing intersectional mentality in the Gay liberation movement meant that even the most privledged within the movement deeply understood the exclusional problems of the gay bars.

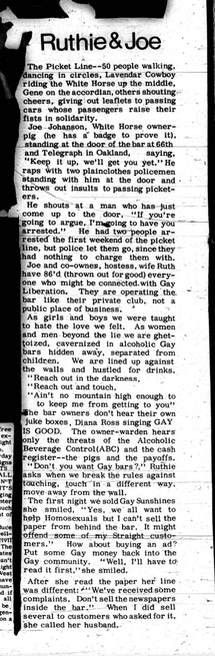

All of these ideas exploded in the East Bay over the White Horse, a gay bar on the border of Berkeley and Oakland. The protests began over the owners of the White Horse kicking out Konstantin Berlandt, a leader of the Berkeley Gay Liberation Front, for trying to sell the first issue of Gay Sunshine inside of the bar. In response, a group of women in Berkeley Gay Liberation organized a Gay Sunshine read-in at the White Horse, and they were also kicked out by the bar owners. At the Berkeley Gay Liberation Meeting the following Monday, the group voted to picket the bar, starting that Friday night. On Friday September 11, 1970, the Berkeley Gay Liberation began their protest by marking the White Horse with the symbol of Gay Liberation from October 1969.

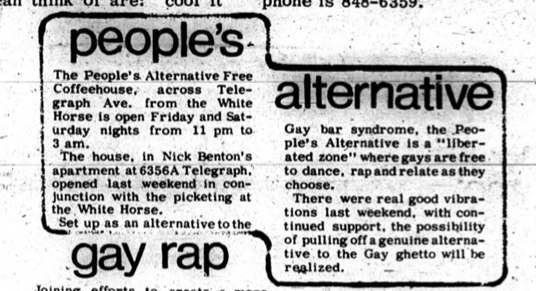

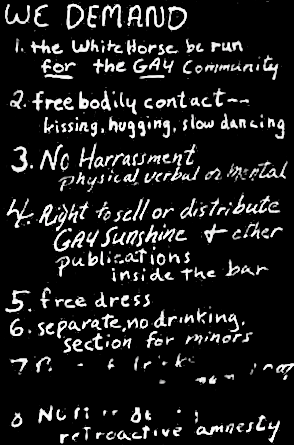

The following Friday September 18, the protesters gathered outside of the White Horse, picketing the bar and celebrating in an alternative space across the street from the bar, called People’s Alternative Coffeehouse. Berkeley Gay Liberation’s Demands were as follows,

The white horse be run for the Gay community

Free bodily contact—kissing, hugging, and slow-dancing

No Harassment physical, verbal, or mental

Right to sell or distribute Gay Sunshine + other publications inside the bar

Free Dress

Separate, no drinking section for minors

Price of drinks lowered minimum 10%

No more 86’ing retroactive amnesty (5)

The protests ended a week later, when the owners of the White Horse agreed to some of the demands put forth by the Gay Liberation Front. However, the Gay Liberation movement went on to continue protests of other gay bars in the Bay Area throughout the late 1970 and early 1971.

(1) Anna Lisa, “Boycott Leonardo’s,” Gay Sunshine, October 1970.

(2) Mike Merry, “Farm Animals,” Gay Sunshine, October 1970.

(3) “Stud Rips Off Gays” Berkeley Tribe, March 5-12, 1971, 18.

(4) James T. Harris, “‘Slanders Bars’,” The Berkeley Barb, Oct. 22-28, 1971, 11.

(5) “We Demand,” Gay Sunshine, October 1970.