A Place for Every Body

For anyone born after 1990, it’s easy to forget that universal accessibility was not a naturally occurring phenomenon.

Indeed, it took decades of direct political action and lobbying by disability rights activists — many of whom were based in Berkeley — to remove social and architectural barriers. Voicing their right to be treated with dignity and respect, these activists opened up access to civil rights, transportation, public accommodations, housing, and independent living services for people with disabilities.

For a window into disability history, let’s visit 1970s Berkeley — or as it was sometimes called, America’s “crip capital”.

Berkeley in the 1970s was a remarkable crucible of disability rights activism, driven by the principle that people with disabilities should be integrated into society rather than housed in institutions and treated as patients first and foremost. Berkeley activists claimed their experience of disability as a kind of expert knowledge which could help rebuild a world for every body.

The materials curated here sketch how crip liberation emerged in Berkeley, with a particular focus on the design side of the barrier-free movement. You can explore how the first curb cuts came to Berkeley and to the Cal campus — through a blend of advocacy, design engineering, planning, and more guerrilla tactics. (A piece of disability lore we investigate: did “midnight contractors” blast curb cuts when the city refused to take action?)

You can also delve here into the rich story of how design activism on the Cal campus, led by Professor Ray Lifchez, helped “crip“ architectural understandings of disability. Pushing strongly against the logic of segregation that he had witnessed in schools and mental hospitals on the East Coast, Lifchez launched a new model of architectural education and practice, in which people with disabilities would offer their expert knowledge and be integrated as consultants and co-teachers in architecture courses and design studios.

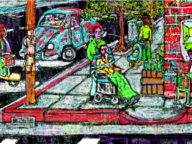

Patrick Connally’s “The First Curb Cuts” (detail)

Behind the disability rights movement was a larger vision of how, when a society guaranteed accessibility for those with disabilities, the benefits went far beyond those who were disabled. Curb cuts, for instance, might have been designed first for people in wheelchairs, but they created a more easily navigable streetscape for everyone, improving a wide circle of lives in the process. Look at Patrick Connally’s painting “The First Curb Cuts”: there we see not just a wheelchair user and his companion but also a woman in a walker and a person pushing a stroller, all of them drawn to the accessible ramp.

From the Early Days at Cowell Hospital to America’s “Crip Capital”

For disability rights advocates, Berkeley in the 1960s is remembered as the place where Ed Roberts—in concert with others in the “Rolling Quads”—launched the independent living movement.

Ed Roberts had been 14 when he contracted polio, which paralyzed him from the neck down and required him to use an iron lung, or respirator, to breathe for long periods of time. At a moment when having a severe disability prescribed a life of social exclusion, Roberts endeavored instead to pursue higher education. In 1962, after two years of community college, he applied to UC Berkeley to study political science—and was initially accepted until the university, upon learning that Roberts had polio, tried to revoke their offer. When Ed fought back, the administration negotiated to accommodate him in a wing of Cowell Hospital instead of a dormitory, making Ed the first student with a severe physical disability to attend Berkeley.

By 1967, twelve other students with severe physical disabilities had joined the program at Cowell. Inspired by the political activism of the decade, the Cowell residents began to see themselves as an oppressed minority, and founded the activist group the Rolling Quads. Drawing from the civil rights movement, these students saw their unequal and unfair treatment on the basis of disability as discrimination. When the Department of Rehabilitation decided it would only fund students who were prospectively employable and would send the rest back to a nursing home, the Rolling Quads protested and went to the local papers.

News of the Quads’ protest against institutionalization spread nationwide and, as a result, Berkeley’s reputation as a place for people with disabilities to exercise their autonomy grew as well.

The Cowell program became an incubator of insider crip knowledge and of the student activism that drove the independent living movement forward. Residents advocated for self-determination and autonomy: they spread the idea that everyone should have equal access to housing, transportation, and employment in the community, rather than be forced to live in an institution or nursing home.

In 1970, the Rolling Quads formed the Physically Disabled Students Program (PDSP) to provide essential services—attendant care, wheelchair repair, financial advocacy, peer counseling, on-campus shuttles—to disabled students at Cal.

In 1972, with more and more non-students coming to the PDSP for help, Roberts and other members of the Rolling Quads opened the Center for Independent Living (CIL), a non-profit organization that aimed to provide the same independent living services to the rest of Berkeley’s disabled community. The CIL also bridged the gap between previously insular disability-specific advocacy groups, creating a coalition of activists fighting for fair treatment on the basis of all disabilities. Though it had humble, cash-strapped origins—its founders began by leasing a roach-infested two-bedroom apartment—Berkeley’s CIL became a model for “Independent Living” centers worldwide.

Hale Zukas and Eric Dibner: The Hacktivists Behind Berkeley’s Accessible Sidewalks

Cover of The Independent, Fall 1974. Berkeley disability activists roll up one of the city’s first official curb ramps.

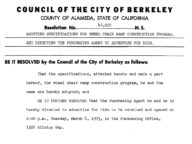

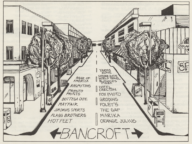

A key line item on the Center for Independent Living’s agenda was the removal of architectural barriers. In 1968 the federal government had mandated, in the Architectural Barriers Act (ABA), that all newly constructed federal buildings needed to be accessible to those with disabilities, but the Act left a significant loophole for past construction. It was in this context that the Rolling Quads lobbied Berkeley’s city council to install curb ramps on existing sidewalks in the Telegraph Avenue area south of campus. The city of Berkeley made the decision to widen these sidewalks, which had been roiled, between 1969 and 1970, by the unrest around People’s Park and were at the center of much of the political and cultural drama of the city.

The curb ramps, which made accessible the stretch of Telegraph between Bancroft Way and Dwight Way, greatly enhanced the mobility options for people using wheelchairs and powerchairs. Their presence on Telegraph, then, sent a positive message to scores of people with disabilities trekking to Berkeley in search of an independent life: “You are welcome here.”

In alignment with the independent living ethos, Berkeley’s first curb ramps were designed by activists themselves — and the most prominent such activist-designer was Hale Zukas, a “grandfather” of the disability rights movement. Still very much active in Berkeley today, Hale can be seen zooming around campus wearing his signature leather helmet, and with an out-of-state license plate fastened to his power chair. Hale was diagnosed with severe cerebral palsy at a very young age, which affected his speech but has not hampered the development of his sharp wit or dark sense of humor. Since Hale retains some mobility in his head, he pilots his chair and communicates by using a head stick attached to the center of his helmet, which he uses to point to letters and phrases on a letter board. While Hale is hard to miss on campus, it seems likely that few recognize the magnitude of his influence on our world, from universal curb cuts to beautifully sloped ramps and federal standards guiding accessible design.

In 1966, Hale came to UC Berkeley to study mathematics; instead of taking up residence at Cowell Hospital, he lived at home with his family. After graduating with a B.A. in 1971, he worked on various projects for the newly created Physically Disabled Students Program (PDSP) before co-founding the Center for Independent Living. After CIL incorporated, Hale assumed the role of community affairs coordinator, a position he held until 1982. In that role, he became a forceful advocate for barrier-free design and accessible transportation, eventually co-founding the BART Accessibility Task Force.

Eric Dibner first met Hale in 1968 while working at PDSP. As an attendant at Cowell Hospital, he developed an interest in accessible housing and design. In their spare time Eric and Hale experimented with duct tape, plywood, paint, and sand to devise some of the earliest curb ramp prototypes, like true makers and hacktivists.

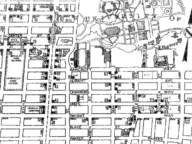

By the summer of 1972, Hale and Eric took to the streets with a young woman named Ruth Grimes, who had recently graduated with a master’s degree in city planning from UC Berkeley. Working under the auspices of the CIL, Ruth, Hale, and Eric spent the summer surveying intersections to develop a comprehensive curb ramp plan for Berkeley.

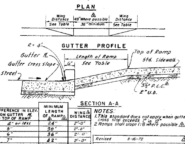

In a major win for the CIL, the City of Berkeley passed a historic resolution a year later which started construction to build the nation’s longest wheelchair accessible route. The Department of Public Works partnered with the CIL to determine curb ramp locations and adopted Hale’s ramp design, which the city used for ten years before Title 24 led to new state requirements. As part of the CIL’s cross-disability consciousness, Hale’s ramp design accounted for the needs of blind pedestrians and wheelchair users by placing the curb ramps outside the main crosswalk.

Not all of the early curb ramps materialized with the city’s permission, however. Responding to delays in the city’s accessibility plan—money was allocated but installation of the new ramps on Telegraph proved painfully slow—some advocates experimented with DIY tactics to improve access. These “midnight contractors” used asphalt to round out street corners, like this corner at Dana and Dwight; among their ranks were Hale Zukas, Eric Dibner, and Michael Pachovas.

The results were crude, but they enabled people in wheelchairs to navigate sidewalks safely. It is these unauthorized, “hacktivist” efforts that stand behind, it seems, the lore that early crip activists blasted curb cuts using nitroglycerin and sledehammers in the wee hours of the morning.

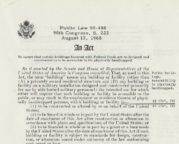

New Standards for Accessibility: How the CIL Shaped Federal Policy

In the years following the construction of Berkeley’s first wheelchair route, hundreds of people with disabilities migrated to the “crip capital.” As more public spaces became barrier-free, attitudes slowly changed in Berkeley. At the federal level, however, there were still great lags in compliance with standards of accessibility. In 1973, Section 502 of the Rehabilitation Act created the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (ATBCB) to better govern accessibility compliance. Part of the new federal law required that the Board solicit input from citizens through public hearings. Recognizing the area’s strides in making public and private buildings accessible, the Board held its first hearing in San Francisco, where members from the CIL made their voices heard.

Hale Zukas joined ATBCB in 1978 and brought to the Board his strengths with public advocacy and his vision, sponsoring an initiative to adopt an entirely new set of federal accessibility guidelines. Four years later, the Board delivered on the promise of that initiative, issuing the Minimum Guidelines and Requirements for Accessible Design (MGRAD). MGRAD was designed to help the Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of Defense, United States Postal Service, and General Services Administration establish enforceable guidelines for access. A decade later, these guidelines informed the federal accessibility requirements mandated by the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA).

Hale Zukas (far right) at a 1983 meeting of the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board in Washington, D.C.

Design for Independent Living: Inside Ray Lifchez’s Studio

“I was guided by the principle ‘Architecture as a social art’.”

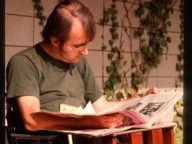

To architect Ray Lifchez, barrier-free design entailed much more than modifying standard curb camps and enforcing access codes. It required a closer look at the social attitudes which informed ways of knowing and being in space.

In the late-1960s Lifchez worked as a part-time professor at Columbia University and as an architect for a New York-based urban design firm specializing in state agencies and public institutions. In 1968, he was sent to Ward’s Island to renovate a large mental hospital. As he spoke, in the hospital and on the grounds, with young residents—many of whom were paralyzed and wheelchair users—he felt that something was amiss: many of the young people in the institution were quite lucid and had much to offer, despite their segregation behind hospital walls. This experience, paired with his early memories of growing up in the Jim Crow South, imprinted Lifchez strongly. He came to the conclusion, as he writes in his book Rethinking Architecture, that “those hospitals and schools were essentially custodial structures to be envisioned for the caretakers, not for the needs of the patients or pupils.”

After Ray was badly beaten by police during the 1968 student strike at Columbia (he had interposed himself between the police and his students), his Columbia colleagues told him that he needed to “cool off”—and arranged for him to start a master’s degree in city and regional planning at Berkeley. Almost immediately after his move out west, he was absorbed by the crip liberation movement. In stark contrast to what he witnessed on Ward’s Island, here he saw people with physical disabilities in the mainstream, embracing independent living and enjoying public life. He connected with the CIL community, collaborating with Hale Zukas, Eric Dibner, and others on the removal of architectural barriers.

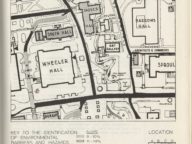

Motivated by a desire to make things better on campus, Lifchez became involved with a series of environmental accessibility surveys. He oversaw teams of wheelchair users and non-disabled architect students conducting large-scale environmental audits of Berkeley’s campus. By cataloguing architectural barriers, the students generated new standards for measuring accessibility. In other words, they made inaccessibility legible and quantifiable, which made it easier to advocate for building modifications. They experimented with new methods of data capture by mounting cameras to researchers wheelchairs at eye level. This way, the reviewer, possibly a Berkeley facilities manager, could get a realistic view from the perspective of someone using a wheelchair as they faced both physical and social deterrents. Their work paved the way for future citizen-based participatory access audits.

In 1972, Ray began teaching a groundbreaking studio course introducing environmental design for disabilities to architecture undergraduates. The studio course was large, enrolling around one hundred students each semester, but it broke into small groups, where students imagined hypothetical personas of people living with some kind of physical limitation. They incorporated accessibility into their designs and wrote mini-biographies about each persona: including their interests, daily habits, sexual orientation, intimate relationships, aspirations, family life, and aversions.

In the spirit of the movement, too, Ray collaborated with the CIL to incorporate disabled “user experts” into the design studio. The studio integrated people with disabilities like Peter Trier, a twenty-six year-old philosophy PhD candidate with muscular atrophy, to encourage students to disregard stereotypical assumptions they held about disability. The course emphasized the “expert knowledge” tied to having a disability and recognized the multi-faceted identities of disabled consumers. Importantly, it focused on accommodating the needs of people with disabilities rather than on simply assimilating them into an able-bodied world.

Lifchez and Winslow’s book, a landmark in the field of accessible architectural design

Based on experiences observing student interactions with design consultants, Lifchez and grad student Barbara Winslow realized it was important to share the Berkeley model with design professionals, planners, sociologists, and healthcare workers. In 1979 the two published Design for Independent Living: The Environment and Physically Disabled People, a landmark work which showcased the inner lives of people with disabilities, the ad hoc design interventions adopted by people at home, and the resourcefulness of Berkeley’s crip community. The book, dedicated to the CIL and now considered a pathbreaking text in disability studies, distinguished between rehabilitative and crip approaches to environmental design.

Accessibility, Lifchez and Winslow suggested, went far beyond “meeting government regulations, building ramps, or adapting bathrooms and kitchens”: it required designers to take an up-close and personal look at their personal bias towards different types of bodies. Design for Independent Living signaled an important shift in design perspectives: unlike previous rehabilitation design manuals, it sought to create, with empathy and respect, individually responsive spaces for people with disabilities. A year after its release, it was nominated for the American Book Award in Non-Fiction.

The success of Lifchez’s introductory course led to the creation of a second project, “Architectural Design with the Disabled User in Mind,” which sought to continue making disability an integral part of design education at Berkeley in the early 1980s. Integrating tenets of accessible design into architectural education was virtually unheard before Lifchez and Winslow’s class. The watershed studio experience was captured in the 1984 documentary, “A House for Someone Unlike Me”, directed by Bruce Bassett and produced by the National Center for a Barrier Free Environment’s Adaptive Environments Center. The film shared the creative design process and methods employed by Cal architecture students, while considering the points of view of the course’s instructors, Peter Trier and other disabled design consultants, and the students themselves.

On January 23, 2018, the Center for Independent Living honored Ray Lifchez with the Ed Roberts Day Award for his contributions to the field of universal design education.

Mary Ann Hiserman (1947-1997)

Mary Ann Hiserman tirelessly advocated for accessible design in hopes of creating a better, just world.

One of Ray Lifchez’s design consultants was an architecture student herself, Mary Ann Hiserman. Among her many achievements, Mary Anne was the first wheelchair user to graduate from Berkeley’s architecture program.

In the spring of 1972, Mary Ann came to Cowell Hospital program when she was twenty-five years-old. Until then, her parents acted as her sole attendants and rarely allowed Mary Ann alone for long periods of time. In early childhood, Mary Anne contracted polio and rheumatoid arthritis, which provided her with only partial use of her hands and arms, Without much exposure to people with disabilities, Mary Ann was reticent to join the program at first, but eventually resolved to give it a try. When she entered Cowell, she was the only woman of eleven residents.

Initially, university admissions questioned whether she could successfully keep up with the architecture curriculum. Ray had confidence in Mary Ann’s moxie and abilities, though, and he persuaded the department to admit her to the program. According to Ray, her peers were incredibly accommodating and Mary Ann was not afraid to ask for help. In Rethinking Architecture, Ray remembers her peers’ hospitality:

“Mary Ann joined a group of students who indicated enthusiasm in having her as a member of their design team. Of their own accord they lowered their workstation to allow Mary Ann to be visually and manually involved. Things went amazingly well. Students assisted her with models and drawings when her manual dexterity failed. Mary Ann was not shy and spoke easily and interestingly about her daily encounters with the built environment.”

Mary Ann’s confidence and grit led her to become the first wheelchair user to receive an undergraduate and master’s degree in architecture from UC Berkeley. As an advocate for barrier-free design, Mary Ann dedicated her personal and professional career to access. She worked on the first campus’ architectural audits, consulted on accessibility booklets for the California Department of Rehabilitation, and became one of the first state architects of California with a severe physical disability.

Mary Ann Hiserman shooting a modified bow-and-arrow in archery class, from Ed Monroe’s CIL mural (photo by Eduardo Pineda)

Mary Ann was memorialized in a 75-foot long mural painted in 1977 at the original CIL headquarters at 2539 Telegraph Ave. Local Berkeley historian Tom Dalzell reported on the mural in 2016, shortly before it was destroyed by private developers to make room for a mixed-use complex. The mural, which rendered a number of central figures of the disability rights movement, depicted Mary Ann at an archery class, pulling taut a specially modified bow-and-arrow.

Accessible Futures

By the 1980s, the barrier-free experience in Berkeley became an aspirational model for cities, designers, and architecture programs across the United States. The crip liberation movement had shaped a landscape where people with disabilities could be seen and treated with dignity, but there was still a lot of work to be done. And there still is.

After the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was signed into law with bipartisan support on July 26th, 1990, a new generation of people grew up taking curb ramps, bright signage on buses, automatic doors, and accessible seats in college auditoriums for granted. Yet at the moment of this writing (May 2018), these gains have been imperiled: the election of President Donald Trump and the Republican control of both houses of Congress has meant the proposal of discriminatory bills like H.R. 620, which aim to pull back on hard-won public programs and services and to deny the universal right of accessibility. At this fraught moment, it’s critical we remember how we got here. We cannot forget the days when people in wheelchairs had to use driveways to cross the street, or were treated as patients in their own home.

— Alexandra von Klan

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank Professor Sue Schweik for her expert consultation during this project’s earliest phase, which unlocked countless discoveries running through Berkeley’s crip lib movement. Notably, this project would not have been possible without Professor Ray Lifchez’s steady stream of enthusiasm and support during regular office hour visits, or his willingness to donate personal visual resources up until the very end.

The author is indebted to the momentum of Berkeley’s disability community writ large, but particularly the following advocates who shared their time, energy, and expertise during informal interviews: Fred Collignon, Jim LeBrecht, Joan Leon, and Zona Roberts. Their personal testimonies rounded out contextual clues and provided ample fodder for further research investigation.

Finally, the author wishes to acknowledge Professor Scott Saul for his unwavering encouragement during every step of the archival process. His thoughtful cultivation of students’ academic curiosities and his devotion to digital humanities are nothing short of inspiring.

Additional Resources

Aimi Hamraie, Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Universal Design (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017).

Raymond Lifchez and Barbara Winslow, Design for Independent Living: The Environment and Physically Disabled People (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979).

Raymond Lifchez, Rethinking Architecture: Design Students and Physically Disabled People (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987).

Fred Pelka, What Have We Done: An Oral History of the Disability Rights Movement (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2012).

Bess Williamson, “The People’s Sidewalks,” Boom California 2:1 (Spring 2012): 49-52.

An invaluable digital resource, worth highlighting, is the Disability Rights and Independent Living Movement oral history collection, curated by The Bancroft Library, University of California, Berkeley.

We Won't Go Away (1981), a British disability rights documentary with a focus on Berkeley

A House for Someone Unlike Me (1984), a documentary on Ray Lifchez and Barbara Winslow's innovative accessibility-oriented design studio