The San Francisco Oracle — an underground publication, based in Haight-Asbury, with a print run of almost 125,000 copies per issue in 1967 — did not specifically cover trends in fashion, but the paper’s recurring themes do suggest how a larger interest in “alternative ways of being” shaped countercultural fashion.

We might ask: where did the Native American influence on clothing come from? And what message did the predominantly white youth of the counterculture aim to send by incorporating Native American garb into their wardrobes?

Allen Cohen, editor-in-chief for the Oracle at its height, suggested in retrospect that “the hippies… shared with the Indians a sense of cultural alienation from American society. There was a general perception that urban society was a cancer and a scourge upon the earth, and that the destiny of the hippies was to begin a gentle reinhabitation of the land.” In this vision, the hippies would learn from “American Indian tribal life before the Europeans.” In 1967, around the Summer of Love, Cohen and the Oracle‘s staff dedicated an entire issue of the Oracle to a set of pieces exploring the “American Indian Tradition.”

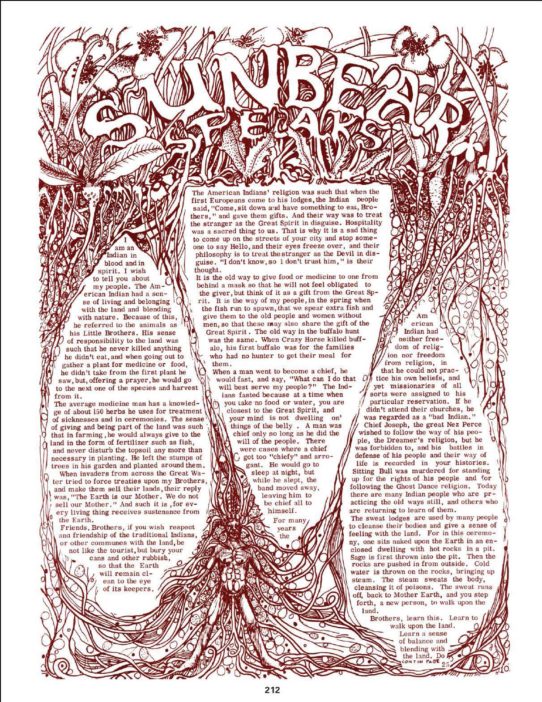

In this piece from that issue, the editors profiled Sun Bear, an “Indian medicine man” who testified to how his people “had a sense of living and belonging with the land and blending with nature.” They did so, however, in a particular fashion: by reprinting the words of his interview while giving no information about Sun Bear’s background, age, or particular tribal affiliation. As a result, Sun Bear seems less of an individual and more of a mouthpiece for countercultural dreams.

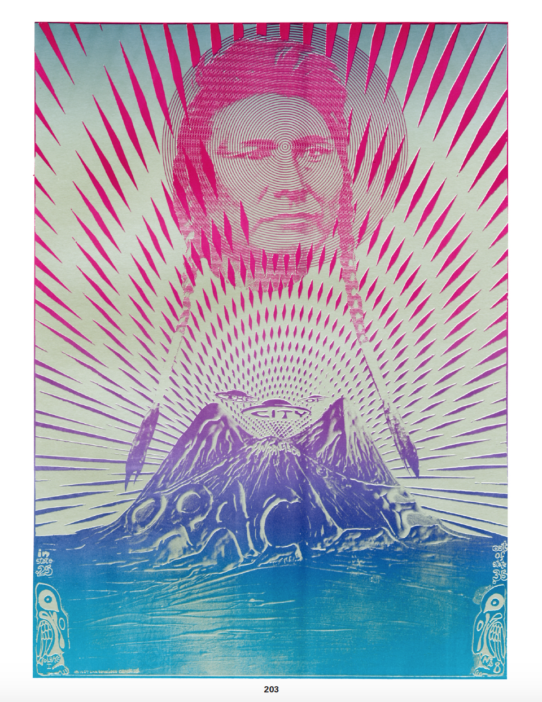

The cover illustration of this issue featured a pink-tinted Native American face hovering over a volcano-shaped island, with three UFOs (bearing the word “CITY”) hovering themselves over the peaks of the island. The figure of the Native American had been self-consciously given the psychedelic treatment.

***

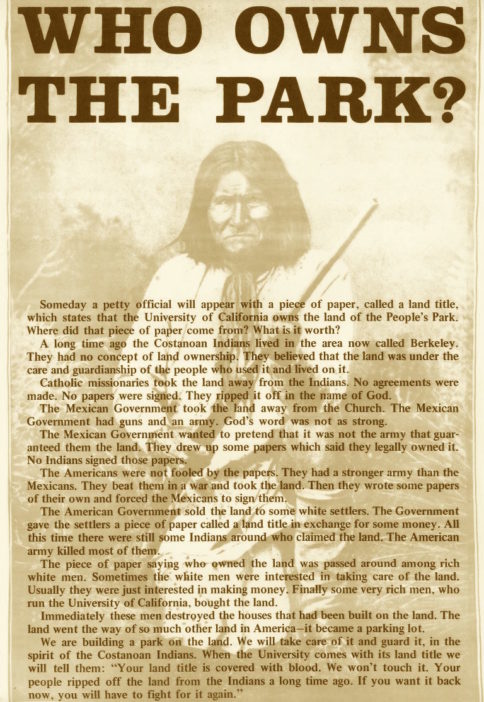

When thinking about how Bay Area hippies drew upon Native American culture and clothing, it is important to consider the battle over People’s Park. Below is the “Who Owns the Park?” flyer, an important 1969 manifesto that stood behind the movement to occupy the land. “Who Owns the Park?” argued that the university-owned land had been stolen from the Costanoan tribe by the American government before being transferred to the university. Justifying the reclamation of the property, activist Frank Bardacke suggested—in a new collective voice that spoke to a new sense of “we the people”—”We will take care of it and guard it in the spirit of the Costanoan Indians.”