The Rainbow Sign

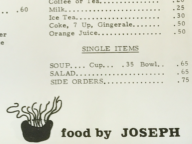

The Rainbow Sign, a Berkeley Black cultural center active between 1971 and 1977, was capacious in every sense of the word. On a typical visit, one might take in the latest sculptures by radical expatriate artist Elizabeth Catlett, run into Maya Angelou reading on the sofa with a glass of wine, and see a group of folks—from, say, a Jewish organization or Oakland’s Black Muslim Bakery—streaming into a meeting in the club’s rentable conference room. Over it all would waft the aroma of soul food, served seven days a week from the on-site restaurant. Amid the clink of dishes in the program hall, there would be the clamor of concert preparations—tables and chairs being moved to make way for microphone stands and drum sets. And bustling throughout would be a dynamic woman in a bold-patterned dress—the charismatic Mary Ann Pollar—smiling, smoking, and orchestrating her vision.

“A Black Table at Which Everyone Is Welcome to Eat”

In values and practice, Rainbow Sign was somewhere between a Black Nationalist headquarters and middle class social club, allowing it to make comrades of a wide spectrum of individuals, including members of the Black Panther Party and Warren Widener, Berkeley’s first Black mayor. It wasn’t simply a stylish lounge and it expressly was not a juke joint. Brainstormed into existence by eleven Black women, with ties to the professional world, who were at least in their thirties, it aspired to have ‘class.’ Yet its unifying characteristic was a commitment to plurality and a vision of Black culture’s central role in securing a just future for all.

When it came to naming the center, concert promoter Mary Ann Pollar drew from two lines of the Black spiritual “Mary Don’t You Weep,” themselves famously repurposed by James Baldwin: “God gave Noah the rainbow sign/ No more water, the fire next time.” One of the most celebrated pieces of American nonfiction of the 20th century, Baldwin’s The Fire Next Time (1963) reframed God’s biblical wrath as a warning to white liberals, blind to their complicity in maintaining white supremacy. In the best-remembered section, Baldwin shares a letter to his nephew sent on the 100th anniversary of enslaved Africans’ emancipation. Readers of The New Yorker (which published the book’s main essay), who might have felt little connection to Black urban communities and who struggled to understand why dozens of American cities were erupting with violent rage throughout the decade, were invited by Baldwin behind the scenes of Black emotional and political life.

James Baldwin with Mary Ann Pollar at a 1976 Rainbow Sign event

Mary Ann Pollar had a great affinity with Baldwin. They shared a politics based on love for “the other,” like that embodied by Martin Luther King, Jr. At the same time, both Baldwin and Pollar tended toward a Black Power-inflected commitment to self-determination. Baldwin argued against what he called “sentimental love”: for him, to love someone meant to hold them accountable. Loving America, in other words, meant forcing its white citizens to reconcile themselves with history and urging Black Americans to be wary of integration into a white supremacist society. The opening of the Rainbow Sign in 1971, eight years after The Fire Next Time’s original publication, marked a new extension, a new repurposing, of the same Biblical rainbow.

Rather than using the verse to accentuate the problem, Mary Ann Pollar and a small group of Black Berkeley community leaders used it to embody their vision for a solution. As a concept and organization, the cultural center was meant to exist as a bridge across all borders—ethnic, national and political. Rainbow Sign concerned itself with sustaining and strengthening the diversity essential to any viable movement toward the liberation of all people. Tellingly, it was located on Grove Street (now Martin Luther King Jr. Way), a historic border between Black and white Berkeley.

Most of us will never know what it felt like, exactly, to be a guest at Berkeley’s Rainbow Sign. Yet by looking at the images, examining the documents and listening to the music, it is possible to catch a sense of the spirit of the place and its people. Our hope is to share with viewers the joy that we’ve felt at our discovery of each new page of this story. (Curiously, Rainbow Sign is not even name-checked in many standard accounts of Black cultural institutions of the 1970s.) The more we looked, the more we found that suggested the significance of Rainbow Sign—to the Black Arts movement, to Black feminism, and to a multicultural and transnational vision of Berkeley in the 1970s.

A New Kind of Black Arts Venue Opens

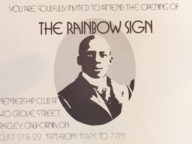

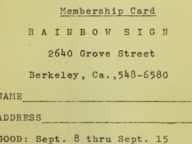

What is immediately evident in even a cursory survey of the club’s promotional material is the incredible range of services offered and the expansive community they aimed to serve. More than a performance venue and arts gallery, more than a “facility for rent and use by the total Bay Area community,” and much more than a restaurant and bar, Rainbow Sign was greater than the sum of its parts. “Rainbow Sign has become a second home to some, a special oasis to many and a mecca for most,” its organizers wrote on the occasion of its first anniversary. “We have been greeted, touched and protected with warmth and enthusiasm…It has been beautiful.” The membership materials and brochures offer a tidy encapsulation of Rainbow Sign’s vision in the organizers’ own words. The floor plan and photographs suggest how members and visitors were ushered through a series of rooms, many quite elegant, and all open to varied use.

What is immediately evident in even a cursory survey of the club’s promotional material is the incredible range of services offered and the expansive community they aimed to serve. More than a performance venue and arts gallery, more than a “facility for rent and use by the total Bay Area community,” and much more than a restaurant and bar, Rainbow Sign was greater than the sum of its parts. “Rainbow Sign has become a second home to some, a special oasis to many and a mecca for most,” its organizers wrote on the occasion of its first anniversary. “We have been greeted, touched and protected with warmth and enthusiasm…It has been beautiful.” The membership materials and brochures offer a tidy encapsulation of Rainbow Sign’s vision in the organizers’ own words. The floor plan and photographs suggest how members and visitors were ushered through a series of rooms, many quite elegant, and all open to varied use.

Ain’t That Bad, Ain’t That Black, Ain’t That Fine: Performing Arts

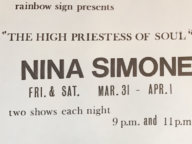

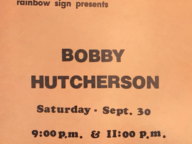

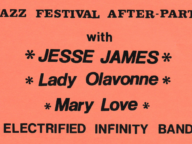

In Mary Ann Pollar’s long and successful career as a concert promoter she developed many strong relationships with musicians and entertainers—relationships which she then tapped to bring a wide variety of acts to Rainbow Sign. In addition to offering concerts by well-known performers from Odetta and Nina Simone to John Handy and Bobby Hutcherson, Pollar’s Rainbow Sign stage was a place for emerging local artists to show their stuff. With piano recitals and Afro-Cuban combos, mime and dance performances and original theater, Rainbow Sign kept Grove Street humming with culture.

My Dungeon Shook and My Chains Fell Off: Literature and Liberation

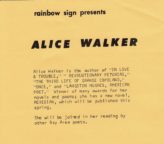

Authors comprised a prominent wing of the Black Arts movement, not simply because they wrote the fiction, poetry and plays that would be canonized as black literature, but because many of the same authors were the first critics of Black art as well as theoreticians of a Black aesthetic. While LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) was in New York City analyzing music through the lens of Black Nationalism, patron saint of the Rainbow Sign and regular guest James Baldwin was in Berkeley, promoting what is perhaps the first sustained work of Black film criticism, The Devil Finds Work. Maya Angelou, a towering figure in Black literature, had moved to Berkeley around the same time as the Rainbow Sign’s founding and was a fixture at the center.

Rainbow Sign fostered multiple literary communities at once. When critic Clyde Taylor witnessed a reading by the jazz-shaped poet Jayne Cortez, he underlined how “the young women of color, poets, feed at her mouth, looking for themselves, their look”: the event helped generate a multi-racial and woman-centered literary community. On another occasion—a poetry marathon in July 1975 that extended over 145 hours, gave a stage to over 200 poets, and earned a distinction in the Guinness Book of World Records (!)—Rainbow Sign modeled a literary community without borders, featuring poets from Beat legend Lawrence Ferlinghetti and later National Book Award winner Joyce Carol Thomas to a great number of lesser known writers.

Other notable figures who made at least one appearance at Rainbow Sign were Nigerian playwright Wole Soyinka (the first African Nobel laureate), Roots and Autobiography of Malcolm X author Alex Haley, and novelist Rosa Guy, who had helped cofound the influential Harlem Writer’s Guild in 1950.

Aunt Jemimas and Jazz Masks: A Fresh Vision for Black Art

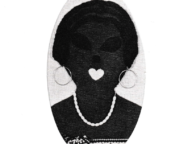

Betye Saar’s “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” (1972)

Rainbow Sign’s gallery brought world-class Black artists to Berkeley at the same time as it fostered the education and exposure of artists close to home. E.J. Montgomery, Black Art consultant for the Rainbow Sign, strove to “involve the total community in the Black visual arts and the Black media”; she also was committed to conveying the Black experience without limiting its definition, which helps explain the wide spectrum of visual styles on offer at the Rainbow Sign during its heyday. (After her tenure at Rainbow Sign, Montgomery would herself become an artist of note and organize over 200 exhibitions as curator.)

The Black artists who exhibited their work at Rainbow Sign channeled, in inventive ways, four of the main impulses of Black art of the time: first, to question and critique prevailing media representations of “Blackness”; second, to create new representations of a liberated Black selfhood (sometimes through recourse to languages of abstraction); next, to strike a balance between racial dignity and pan-racial humanism; and lastly, to recenter American history around African-American history.

The roster of artists who exhibited and lectured at Rainbow Sign—figures such as Romare Bearden, Elizabeth Catlett, and Betye Saar—constitute a virtual ”who’s who” of Black visual art of the second half of the twentieth century. Saar’s Liberation of Aunt Jemima—a piece that, according to writer-activist Angela Davis, marked the start of the Black women’s movement—was created especially for a Rainbow Sign exhibition.

Many of Rainbow Sign’s featured artists were often committed as well to lecturing and teaching art, making their impact on the community and the next generation all the more wide-reaching.

A Closed Fist is Very Strong: City Politics, American Politics

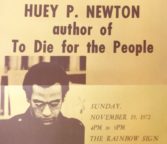

At a time often defined by paranoia, state repression, and the decline of social movements on the Left, the Rainbow Sign passionately fostered diverse community and supported black public figures with a wide range of political tendencies. It is remarkable that one venue hosted Huey Newton, who helped found the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense in Oakland, as well as Warren Widener, Berkeley’s first Black mayor, who backed away from the issue of community police oversight in order to get into office.

The Sign was an intellectual environment where any resident could hold their own dialogue, participate in workshops, raise funds for a variety of causes, keep in touch with Black leaders and keep up with Black thought. By the same token, Black leaders like Newton and Widener came to the center to take the pulse of the Black community.

If a single piece of art could sum up Rainbow Sign’s commitment to a political coalition across all differences, it might have been an Elizabeth Catlett sculpture of a fist sprouting two heads, of which she said, “It’s a portrayal of a saying by Diego Rivera…’An open hand with its fingers spread is very weak, but a closed fist where all of the fingers are together is very strong.'”

Look About You, Think About This: Education Pending Revolution

According to Mary Ann Pollar, education was priority number one on the Black agenda, and at the Rainbow Sign. “Hidden under everything we do, the best entertainment we put on,” she said, “there’s always a message: Look about you; think about this.” Whether education took the form of film screenings, Swahili courses, grant-writing classes, travel plan tutorials or lectures from the foremost thinkers in the Black Arts movement, Rainbow Sign took seriously the notion that education was the key to realizing the full potential of any individual or community.

Yet programming such as this was only one way that the Sign advanced its pedagogical project; in a broader sense, every aspect of the center was meant to lead by example and model the set of values required to generate and sustain coalition-based social movement. Club membership was largely made up of professional educators and several of the staff had backgrounds in educational fields, Oakland school board candidate and consummate trouble-maker Electra Price foremost among them.

To a large extent, Rainbow Sign’s most important educational function was as a platform for residents and educators in the community to participate in their own edification. As a rentable space, the Sign hosted scholarship committee meetings and award ceremonies, and as an arts venue it exposed multiple generations of Bay Area residents to the Black cultural wealth they had been taught to perceive as inferior. With its diverse programming and multicultural audiences, Rainbow Sign was a model: a vibrantly positive actualization of “what it would be like if people got their act together.”

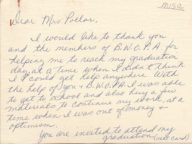

For the Love of People: The Players of Rainbow Sign

Rainbow Sign existed to serve its community and it existed because of its community; its motto—found on fliers and brochures—was “for the love of people.” A handful of very hardworking and dedicated people made it possible. Several of those same people made this project possible as well. Our heartfelt thanks to Odette Pollar, Charles Brown and Electra Price, who shared with us their memories, time and personal collections. In our current cultural moment, marked by heightened xenophobia and racism, recovering the story of such a model of multicultural, democratic collaboration is more important than ever.

— Max Lopez and Tessa Rissacher

Additional Resources

Though there is little scholarship on the Rainbow Sign itself, these resources allow for a broader understanding of the contexts and traditions that shaped it and otherwise gave it meaning.

Lisa Gail Collins and Margo Natalie Crawford, eds., New Thoughts on the Black Arts Movement (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2006).

Brittney C. Cooper, Beyond Respectability: The Intellectual Thought of Race Women (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 2017).

Dayo F. Gore, Jeanne Theoharis and Komozi Woodard, eds., Want to Start a Revolution?: Radical Women in the Black Freedom Struggle (New York: NYU Press, 2009).

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, Righteous Discontent: The Women’s Movement in the Black Baptist Church, 1880–1920 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1994).

Now Dig This!: Art and Black Los Angeles 1960-1980 digital archive. (A richly curated archive of primary and secondary materials, which includes valuable framing essays by Kellie Jones, Daniel Widener and others).

James Smethurst, The Black Arts Movement: Literary Nationalism in the 1960s and 1970s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005).

Robyn C. Spencer, The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender, and the Black Panther Party in Oakland (Durham: Duke University Press, 2016).

KPIX coverage of an Elizabeth Catlett art opening at Rainbow Sign in 1972 (transcript here)

A playlist of music performed at Rainbow Sign