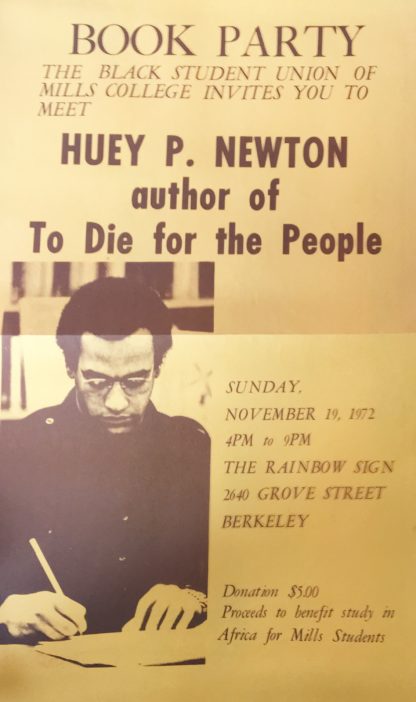

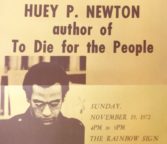

During the Rainbow Sign’s life span, the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense was undergoing a series of transformations before finally collapsing under an assault coordinated by the federal counter-intelligence program known as COINTELPRO, which used tactics such as forging letters in order to sow discord among the imprisoned intellectual leader Huey Newton and the de-facto leader in his absence Eldridge Cleaver.

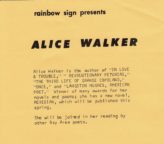

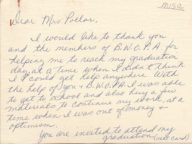

In the early 70s, at the same time that the Panthers moved out from their storefront Berkeley headquarters and into a victorian house in the heart of Black West Oakland at 1048 Peralta Street, they were shifting away from categorical anti-capitalism and toward a conceptualization of Black business people as comrades in struggle with funds to commit toward the impending revolution. This trend, scholar Robin C. Spencer points out in her book The Revolution Has Come: Black Power, Gender and the Black Panther Party in Oakland, put the panthers “on the same terrain as Oakland’s Black middle-class establishment, a group they had vocally condemned in the past.” This change in heart was hard for some Black business owners to swallow, particularly when they were threatening to boycott businesses that refused to donate to their cause. The Rainbow Sign existed in a liminal space between middle-class social club and radical organizing venue, a balance perhaps best attested to by the fact that the Panthers never demanded a tribute from Mary Ann Pollar.