This article explores the diversity of the flourishing San Francisco Bay Area’s women’s music community. It is mentioned that many of the women in the community, including the women in the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective, play “typically male-associated instruments” such as electric guitar, bass, drums, and horns.

***

In a recent interview, Nancy Vogl spoke about the perceptions of women’s music and how the band overcame their isolation from the dominant music industry:

Lily: It seems that there’s sometimes a perception about women’s music that the message conveyed is more important than the quality of music and I think that leads some critics to not really understand (the music) and just say, “Oh it’s not that objectively good.”

Nancy: I think that’s a very, very, real perception and it impacted me a lot. Because I had been exposed to classical and commercial music all my life and had experience with playing, my value system said “Well, to play guitar you have to be this good, to play bass you must be this good, the music has to sound this professional or it’s inferior.” It was a challenge to move beyond that, “I suck” mentality.

We knew in our hearts what we were doing was valuable but from an objective point of view, in many ways we lived up to that criticism. For example, Debbie decided to learn drums a year into the band and immediately performed with us. Our vocals were heartfelt but not “good enough” for radio play at that time.

When we began to deconstruct all domains of power in society, we found a whole other way of looking at it though, and realized that the men who created the bar of judgment had benefits that had never been acknowledged – their ability to practice hours a day and to become technically proficient – nearly every one had mothers or girlfriends who were doing their laundry, cooking for them or doing their dishes! I realized that the standards in many domains of culture were set by those with an unequal advantage. That was a key message for me.

A boyfriend in LA (before I moved North) practiced with his friends for hours, and I couldn’t stand sitting and playing with 7 days of crusty dishes and cockroaches in the sink; this was irrelevant to them. They just wanted to play all day and night but I had already been socialized to be caretaking; I simply could not ignore it. Not an excuse, just my reality. If you are an exception and a protégé being acknowledged and supported to develop your prowess, it’s great, but that’s still the exception.

Womens’ socialization was that we have a whole world to take care of, not just isolated issues. Our music promoted the idea that (like Remy in the cartoon Ratatouille) “Everyone can play”. We wanted women to have more accessibility to art than we had traditionally be “allowed” to have.

Until recently, the patriarchal standard of fine art had dissed folk art, yet there’s a power and a potency in folk art that that renders that distinction irrelevant. They’re different, but each plays a role in culture.

Still, I was always a bit stuck in that netherworld of judgment. “I suck” one day and “Fuck that old shit” the next. What helped me grow was being completely moved by my peers. Some thought Debbie didn’t have a great voice, yet I experienced her transfix a hundred women hearing her song “Nicky”, about her girl scout camp experience. You could’ve heard a pin drop because what she was expressing touched every cell of every woman in that room.

I think the BWMC kind of teetered on that balance too. Maybe we weren’t the best technicians or our recordings weren’t that “good”, but we were passionate enough to try. In 1976, Suzanne had never touched a studio sound board before and said “Oh, let’s make an album.” She started from absolutely nothing, with no experience at all, and we emerged with a very important document of ourselves and the movement at the time.

It boils down to “We didn’t know shit, but we made stuff happen”. We didn’t know how go on tour, never made T-shirts, posters and other merch, but thousands of women shared resources with each other. Our musician friend even loaned us her van for our first 3 month national tour.

After us, came Grunge and I marveled at the adoration.

Nirvana said, “Fuck disco. We’re gonna play as loud as possible with few chord changes” and I couldn’t help but see the ways patriarchy is so deeply embedded that only men were allowed to disrupt the rules that other men had created.

They took the traditional standards for the industry and totally disrupted them. We did too, but with our consciousness and the feminist political ideology coming through our music – it tilled the cultural soil for the Women’s movement to thrive. The tradition of the male perspective did not value this. Also, we were process oriented – lyric heavy and, in the service of a bigger message.

***

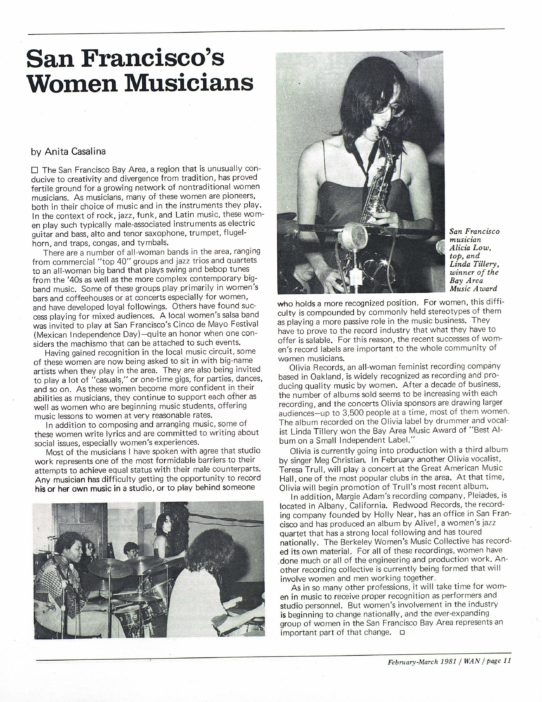

The article notes that for most female musicians, studio work and experience are the most formidable barriers to overcome in terms of reaching equal status with their male counterparts. It is already challenging for musicians to get the opportunity to record their own music in a studio setting, and for women, this difficulty is “compounded by commonly held stereotypes of them as playing a more passive role in the music business.”

Although the article is not focused on lesbian or feminist-identified bands, the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective is mentioned for its resourcefulness in overcoming this barrier by recording their own albums.

***

In a recent interview, Suzanne Shanbaum spoke about the recording process for the band’s first album and the challenges they faced along the way:

Suzanne: I was really into arranging and producing. At that time, I knew what I wanted to hear in the music, but I didn’t know how the industry worked and I didn’t have any training or role models that could teach me how to approach the role of arranger or producer.

At the point where we had all the material to make an album, we memorized all of the songs and the instrumental and vocal arrangements. Our next step was to find a woman engineer. In 1975, there were no women engineers in the Bay Area but we discovered that there was a woman at Mills college who was an assistant engineer working a couple of nights every other week.

We arranged our schedules so that a couple of nights every other week we would go to the Mills studio and spend what time we had working on our album….and that’s how we did it. We did the whole album for $5,000, pressed, cover, recording, mixing, mastering, everything.