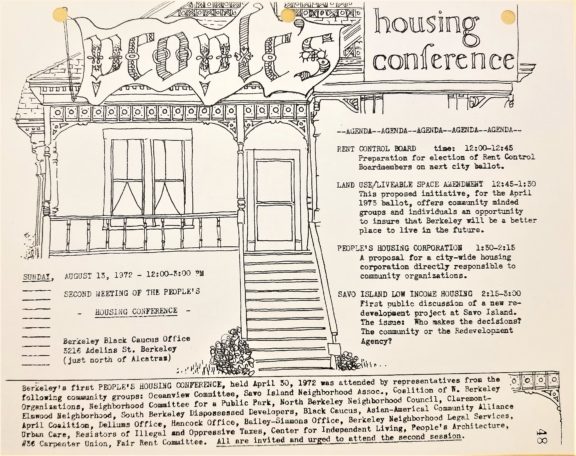

This flyer advertises the second “People’s Housing Conference,” to be held on August 13, 1972 at the office of the Berkeley Black Caucus. The location was not accidental, as NPO activists were concerned with the exodus of Berkeley’s African-American population, but preservation measures were ultimately ineffective in addressing this demographic change.

The initial conference, held April 30, 1972, had brought together a broad swath of progressive groups, including the Ocean View Committee, various neighborhood associations, the April Coalition, representatives of Councilmembers Hancock and Dellums, the Center for Independent Living, and People’s Architecture. The conferences were intended to address a wide range of housing issues by networking between Disabled Rights advocates, ethnic minority representatives, rent control activists, and neighborhood preservationists. The agenda contains four topics: Rent Control Board, Land Use / Livable Space Amendment, People’s Housing Corporation, and Savo Island Low Income Housing.

Berkeley passed Rent Control legislation in 1972, although it was struck down in court the following year on procedural grounds. Not knowing that the Rent Control Board would soon cease to exist, attendees of the People’s Housing Conference sought to identify candidates and form a voting bloc. In the tumultuous political scene of Berkeley in the 1960s and 1970s, coalitions were essential to winning elections.

The “Land Use / Liveable Space Amendment” was a working title for the NPO, which was still being drafted and revised. After Martha Nicoloff and Ken Hughes sought the opinions of renters’ groups and hillside neighborhoods, mandatory low-income housing and down-zoning of the hills were added to the initial idea of stalling demolition.

The People’s Housing Corporation was an idea to create a city-wide public body to oversee housing issues, answering directly to community organizations, essentially circumventing the city government. An even more extreme idea, which radicals attempted to get on the ballot, was communal ownership (not merely oversight) of residential property. This notion was an outgrowth of Berkeley’s well-established tradition of housing cooperatives, but was never seen by moderates as legally or economically feasible.

One such housing cooperative was (and is) the Savo Island Cooperative in South Berkeley. Then still in the planning stages, “Savo Island Low Income Housing” was completed in 1979, at which point 57 families moved in, all with Section 8 vouchers. Intended to racially and economically integrate the neighborhood, Savo Island was a HUD project which served working-class families, seniors, disabled people, and homeless families. Discussion at the People’s Housing Conference was centered around trying to get the Redevelopment Agency and its partners to allow community input on the project.

Nicoloff and Hughes, still in the preliminary stages of planning the NPO, were seeking to unite diverse special interest groups into a preservation coalition. To form a left-leaning bloc, they needed the support of classic Berkeley radicals, neighborhood-minded folks, and students, who made up a large percentage of voters. The People’s Housing Conference was an attempt by the organizers of the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance to build a broad-based, grassroots movement that could take on an oppositional mayor and city council.