Nacio Jan Brown

“When I began photographing on Telegraph Avenue, the scene ran the gamut: flower children and riots, hard drugs and Jesus freaks, left-wing intellectuals and psychedelics, natural foods and runaways. Somehow this variety worked together.”

— Nacio Jan Brown

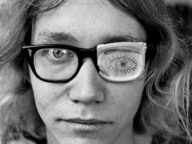

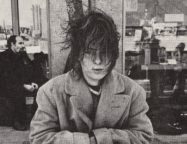

For four years starting in 1969, a young, lanky, mustachioed photographer with an impressive tousled mop of hair made a study of the scene around Telegraph Avenue—a scene that had been his own since he’d learned the art of photography in Cal’s student darkrooms half a decade before. Whether roaming the Avenue or nursing a cappuccino at Caffé Med, he took to toting a binder with a three-inch spine, full of dozens of his own photographs. When he approached people to photograph them, he often offered the binder as proof—that he was a real photographer with a real project, and was coming to it from an angle of sympathy.

The lanky photographer was Nacio Jan Brown. The book that resulted, Rag Theater, is now seen as a classic of street photography, prized for its arresting depiction of the countercultural scene that swirled around Telegraph, and its intimate rendering of the energy and turmoil of the times.

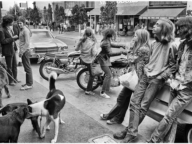

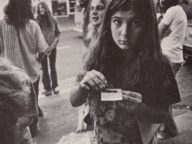

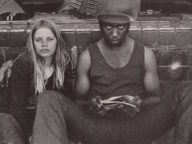

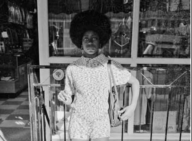

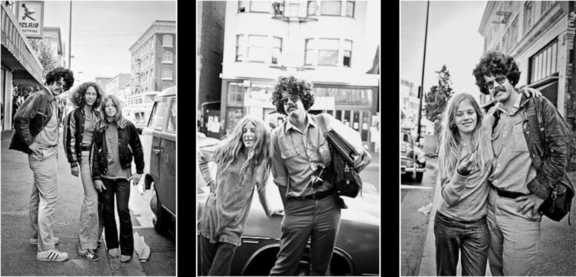

Nacio Jan Brown, with his trusty binder (center photograph) and with some of the teens he photographed in “Rag Theater”

Photographer of the Movement

Nacio Jan Brown began his training in the arts by studying painting at Southern California’s Chouinard Art Institute from 1961 to 1962, but he fell into his true artistic calling when he bought a camera so that he could photograph his mural-sized artworks. “I bought a Mamiya-Sekor [a single lens reflex camera] and as soon as I had it in my hands it was all over with painting,” he recalled.

Making his home in Berkeley in 1965, he studied photography at the Associated Students of California (ASUC) studios, where he both learned about craft and pushed against the dominant “house style,” which led students to produce “contemplative nature studies” in the mode of Edward Weston—photographs of “rocks and trees, and half-second exposures of a stream,” as he remembered it. “I tried to do that and I just wasn’t interested because there was all this political activity going on in Sproul Plaza, which was where all the exciting stuff was happening. And after attempting and failing to become interested in rocks and trees, I was shooting 35mm. But I still had this obsession with quality which I acquired in the darkroom.”

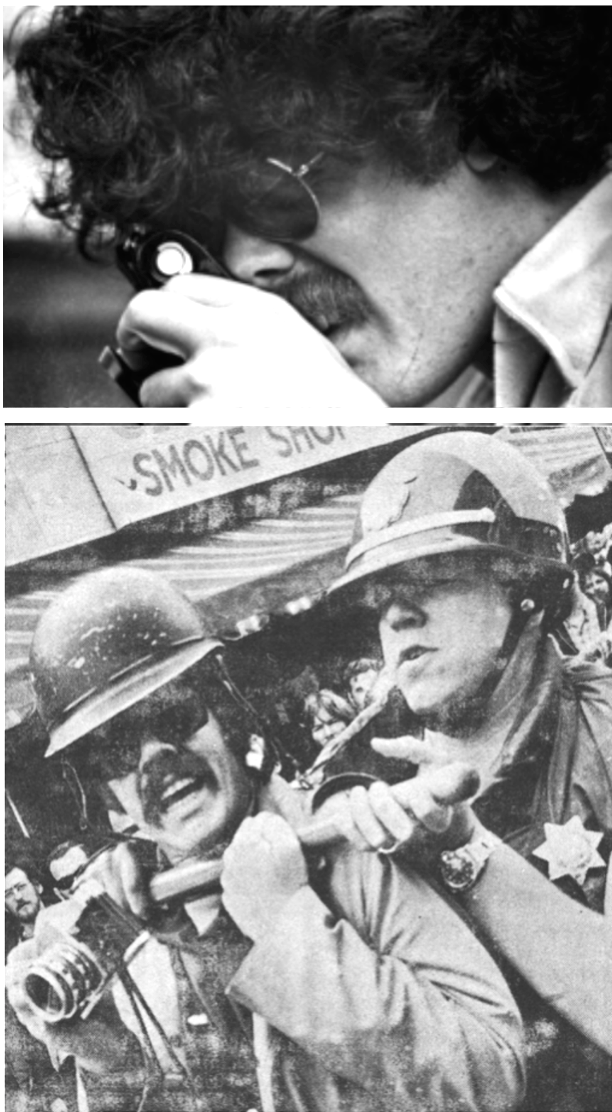

Inspired by the coalescing protest movements—against the Vietnam War, against racism, against police power—Brown thought of his photography as “a craft in service of a cause.” He became a staff photographer for the San Francisco Express-Times, San Francisco’s main underground paper, and for half a decade captured the drama of major and minor protests alike (even if it meant becoming subject to police action himself), his images usually circulating in the underground press but sometimes carried by the Associated Press and mainstream periodicals like Newsweek.

Helicopter spraying tear gas at Cal, May 1969 (photo by Nacio Jan Brown)

Many of his photographs of the time—of a sunrise at Oakland’s Stop the Draft Week; of James Rector shot by police at an action over People’s Park; of a helicopter spraying tear gas on the Cal campus; of Black Panther Huey Newton celebrating his release from prison—stand as iconic markers of the turbulent drama of the late-’60s and early-’70s.

Making Rag Theater: A Story of Two Trajectories

After the battles over People’s Park in the spring and summer of 1969, Brown had a sense that “the underground press scene had kind of peaked and was a bit on the wane,” and so he turned his energies to a new project: a book that would document the world of Telegraph Avenue. More specifically, he would focus on the 2400 block, bounded by Haste and Dwight, that served as a microcosm for the new world being born.

Though Brown had been a regular on Telegraph for five years, he initiated this project at a crucial inflection point in the life of the Avenue, when the utopian dreams of the counterculture allowed for a spirit of peaceful coexistence. “When I began photographing on Telegraph Avenue,” he remembered, “the scene ran the gamut: flower children and riots, hard drugs and Jesus freaks, left-wing intellectuals and psychedelics, natural foods and runaways. Somehow this variety worked together.” A set of hip businesses—the Caffé Med and bookstores like Cody’s, Moe’s, and Shambhala; the poster shop Print Mint and the thrift-store boutique Rag Theatre—anchored life on the 2400 block and supplied the stage set for many of Brown’s photographs.

Two things happened as Brown developed his project over the next four years: the scene on the Avenue darkened, and his craft as a photographer deepened.

The summer of 1969 had been marked by the Telegraph Avenue Summer Project, which aimed to provide food and shelter and health clinics—and serious helpings of good music and theater—to those who made the south campus area their home. Just a few years later, there was an inescapable sense that hard drugs, especially heroin, had made the Avenue a more predatory environment. By 1973, when Brown stopped taking his camera to Telegraph Avenue to shoot photos, those “on the street” were much less likely to be affiliated with the counterculture, and more likely simply to be impoverished and without work. Tellingly, the building that housed the Rag Theatre shop, which had served as a backdrop for many of Brown’s photos and helped fuel the dreams of the figures within them, was itself demolished by the city of Berkeley in 1972.

The cover photograph of Rag Theater (photo by Nacio Jan Brown)

Brown’s Rag Theater subtly captures this trajectory across its pages. Portraits of young people, playfully engaged in self-fashioning or otherwise in high spirits, yield to images that carry a sense of uncertainty, ambivalence, damage, and confusion.

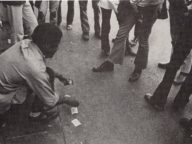

There was another trajectory, too, that is contained in Rag Theater’s pages: that of a photographer experimenting with his craft so as to create images that would be less predictable and more open to the play of the viewer’s eye across the photo.

Brown explained this process of artistic growth in an interview: “[A]s I worked, I became aware of limitations in my work—there were things I needed to learn. One example is that, when I started, I was very good at straight-on, classically composed individual portraits. As I accumulated more and more of these, I saw that, for balance, I was going to have to learn to make other kinds of images.

A downward tilt: Rachel Krech with her dog (photo by Nacio Jan Brown)

“I studied other photographers’ work closely to see what I could learn. I also began to experiment with different ways of using the lenses I had, especially wide-angle lenses. An example here is that I learned how to make effective photographs pointing a wide-angle lens down. The resulting ‘keystone’ distortion, usually a negative, can be effective in the right circumstances. By the end of shooting for Rag Theater, I was, among other things, shooting my subjects from behind, shooting from a variety of distances, shooting in tricky light conditions, and making photographs where there is no easily identified subject matter, where instead the subject matter is diffuse and where the eye wanders here and there around the image.”

Brown was twenty-six years old when he started the Rag Theater project, thirty when he stopped shooting, and thirty-two when he published his book with his own Great Star Press, bearing an evocative foreword by Thomas Farber.

In his photographer’s note to the book, Brown expressed a sense of gratitude to those on the street, as well as a sense of intimacy with the images themselves: “There is a sense in which this kind of photography involves taking something from people without giving them something in return. People reveal something to me, however subtle, which they would normally reserve for those much closer to them. My photographs then show this to others. But this is not so simple. Long after the moment of exposure, when the incident has been forgotten by the subject, I am confronted by it again and again—on the negative, on contact sheets, on proofs, and in prints. The images in this book have become my family.”

After Rag Theater

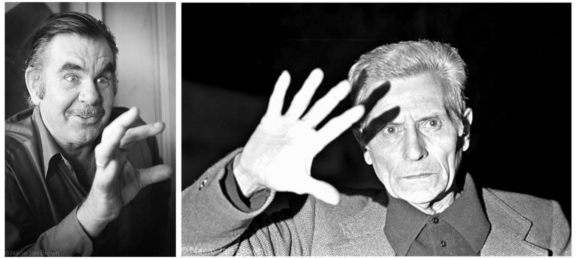

Film director Martin Scorcese (photo by Nacio Jan Brown)

Brown continued shooting photographs after completing work on Rag Theater, creating visually captivating shots of film directors ranging from Martin Scorcese and Lina Wertmuller to Russ Meyer and George Franju. Photography no longer furnished his main source of income, however. He had become a photographer in order to enlist his craft in a cause and, after the fall of Saigon and the full evacuation of US personnel from Vietnam in 1975, he felt that the original cause was no longer there. He started building hot tubs in 1975 and later became a Berkeley real estate agent.

Film directors Russ Meyer and George Franju (photos by Nacio Jan Brown)

In 2011, Brown unveiled ragtheater.com, a website that displays the photographs printed in Rag Theater and other photographs on the rolls that Brown shot for the project. Brown invited those on the Telegraph Avenue scene to contribute their reflections, and their often extensive comments offer a parallel history of the Avenue from the inside, as well as stories of what happened after they left the Avenue behind.

Additional Sources

Nacio Jan Brown, “‘Rag Theater’ and Other Work” (presentation at the UC Graduate School of Journalism) (video), Sept. 2012.

The Leica Camera blog, “Nacio Jan Brown: Eloquent Witness to the West Coast 60s Scene,” Nov. 20, 2012.

The Leica Camera blog, “Nacio Jan Brown: Eloquent Witness to the West Coast 60s Scene, Part 2,” Nov. 26, 2012.

Gabriela Piţurlea, “4 ani pe strada inocenţei pierdute,” Sub 25, Aug. 3, 2015 (English language version of interview available here).

Further Resources

www.ragtheater.com: Nacio Jan Brown has here uploaded all the photographs from the rolls of the larger Rag Theater project. The site also collects testimonials and responses from those who frequented Telegraph Avenue during the time of the Rag Theater project, some of whom are captured in Brown’s photographs.

New signed copies of the original printing of both the paperbound edition and the limited (300 copies), hand-numbered hardbound edition of Rag Theater are available through Amazon.

High-quality gelatin prints of Nacio Jan Brown’s photographs can be ordered from the Joseph Bellows Gallery here.

The young photographer in action, and being restrained by police in May 1969 (bottom photo by Hoffman)