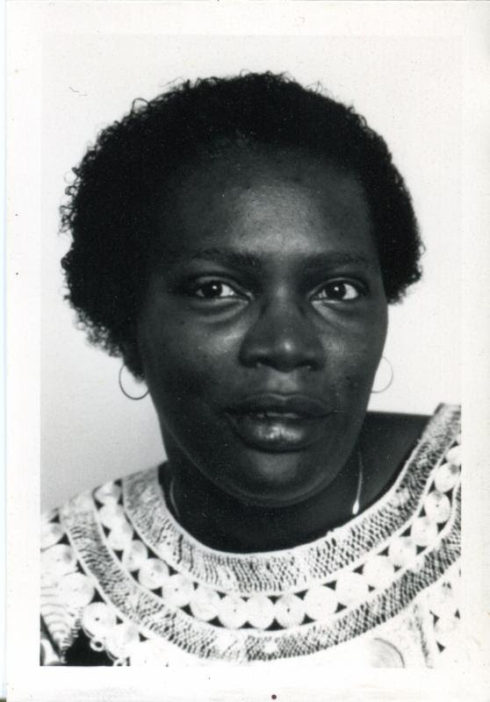

Pat Parker (1944-1989) was a Black lesbian poet who was a founding member of both the Berkeley GWL and the Black Panther Party. She read poetry publicly in Oakland beginning in 1963. At only 18, she was abused by her husband, a Panther and a playwright, causing her to lose her pregnancy that she had at the time. She divorced twice before coming out, and then she founded the Women’s Press Collective. She read her poetry at women’s bookstores and coffeehouses around the Bay. Although GWL’s mostly white demographic affected the lesbian radical scene later in the ’70s, my limited research indicated that its early days were its smoothest. Along with Parker were Linda Wilson and Pat Norman, two other Black lesbians who were involved with GWL from its outset. They were regulars at the lesbian bar in the Haight called Maud’s.

As opposed to the mainstream trend of single-issue politics within the gay liberation movement, GWL’s founding principle was cross-struggle solidarity. Their autonomy was intimately connected to their experience of sexism in the male-dominated movement. Central to the organization was the power of mutual aid in collective households. In their disruption of the capitalist family structure that depends on gender roles, households served as the base for their activism, in which they created regional networks and launched new institutions like bookstores, clinics, and cafes. In the East Bay, GWL had houses in the Mission (Lexington St), central Berkeley (Benvenue Ave), and North Oakland. The SF chapter had houses in the Haight and at Potrero Hill. Details about GWL are extremely limited, most times only available for those who have privileged access to the archives. According the Emily Hobson’s Lavender and Red (2016), Pat Parker “shepherded households” in Emeryville, Oakland, Potrero Hill, and the Haight.

Later, while working as the executive director of the Oakland Feminist Women’s Health Center from 1978 to 1988, she formed the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council in 1980. After a devastating premature death due to cancer, she was inducted onto the LGBTQ Wall of Honor at the Stonewall Inn. Her legacy throughout the ’70s and ’80s is outside the time frame of this project.

In one of her most famous poems, “my lover is a woman,” she explicates the experience of having a white woman lover by highlighting the intersections of race, gender, and sexuality. In another, “where will you be,” she calls on the queer community to not only recognize their own failures to defend one another, but to also consider what their reaction will be when they are directly affected by the oppression of society. Her poem “don’t let the fascists speak,” inspired by an action at SFSU, is eerily relevant to the fact that UC Berkeley approved visits, in the last three years, by Milo Yiannopoulos, Ben Shapiro, and Ann Coulter.