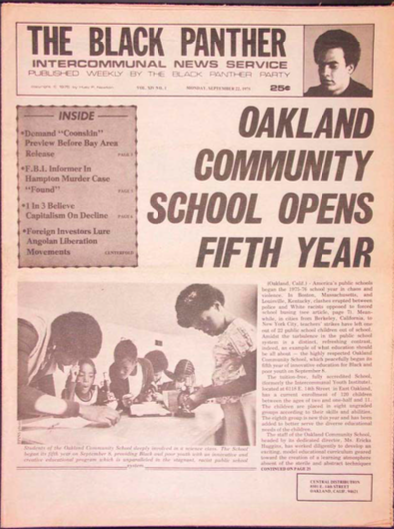

This article, from the Black Panther newspaper, offers a valuable overview of the curriculum and purpose of the Oakland Community School.

Notably, the author of the article judges that the Oakland Community School was beginning its fifth year — an accounting that suggests that, for the author at least, there was a sense of deep continuity between the Intercommunal Youth Institute and the Oakland Community School.

The article opens by discussing how students’ education elsewhere was being disrupted, whether by violent protests to school integration in some states or by teacher strikes in Berkeley. It contrasts this widespread turbulence with the Oakland Community School, “which peacefully began its fifth year of innovative education for Black and poor youths.”

Most students, according to the article, had prior experiences in the “racist public school system which has failed to provide Black and minority youth a meaningful education.”

The Oakland Community School provided a very different educational experience. Students were divided into levels depending on ability, not age. The Youth Committee had direct input on making decisions around academics and activities. The curriculum consisted of Language Arts, Spanish, Mathematics, Speech, Science, Social Science, Environmental Studies, Physical Education, Art, Music Appreciation, Voice.

While the Language Arts, Mathematics, and Spanish classes seem more standard for the time, some features of other classes stand out. In Social Science class (which also encompassed Black Studies), students were asked to draw their own conclusions based on analysis of the facts: “American history, for example, when the facts are examined, is quite different from the public school interpretation that is usually presented.” In art class, students examined the relationship of people’s lives to art, how politics has shaped art, and how art has shaped thinking. The sports program, though often featuring sports found in many schools, also included martial arts, yoga, and isometrics.

The article highlighted OCS’s motto that “The World is a Child’s Classroom.” According to this philosophy, in order to transform a situation, you need to have contact with it. To this end, the curriculum emphasized real life experiences and field trips.

The article gives a sense of how the OCS supported the physical needs of the students, not just their educational needs. The school provided eye, hearing and speech screening, and took care of first aid and emergency needs. It provided, at this point, three meals — breakfast, lunch and dinner —to every student every day. Parents were asked to pay $25 per month, on a volunteer basis.

The article closes with Panther leader Huey Newton speaking to the purpose of OCS and the power of education: “our aim is to provide the young of [marginalized communities] with as much knowledge as possible and to provide them with the ability to interpret that knowledge with understanding. For we believe without knowledge there can be no real understanding and that understanding is the key to liberation of all.”