On October 31, 1969, a group of protesters from the Committee for Homosexual Freedom (CHF), which had recently become the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), allied with The Society for Individual Rights (SIR), organized a protest against The San Francisco Examiner for running an inflammatory article about the Gay bars and community. The article, “The Dreary Revels of S.F. ‘Gay’ Clubs,” written by Robert Patterson on October 15, also called for increased policing and harassment of Gay spaces. However, this article was only one of many written by Patterson, and part of the practice of newspapers printing the names of Gay people arrested during bar raids, systematically outing people, and creating a culture of fear. Ever since the national attention of the Stonewall riots, socially conservative newspapers ramped up their anti-Gay rhetoric and Gay liberations across the country organized similar protests.

Although CHF was created out of a riff between radical Gay activists and the more conservative SIR community, the groups allied together over the shared goal of changing the SF Examiner’s discriminatory practices against the Gay community. Similarly, Berkeley’s Gay Guerrilla Theater and bourgeoning Gay Liberation Front joined the protest.

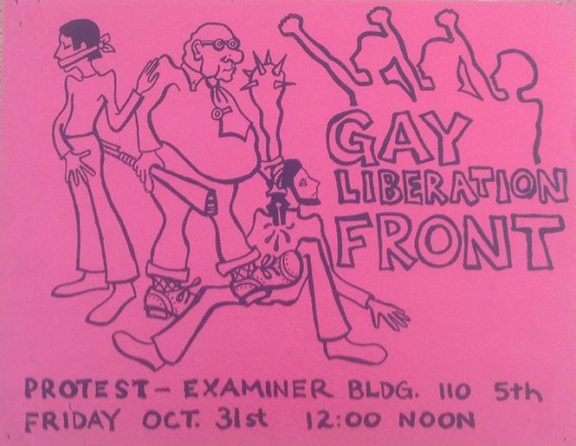

Flyer for Gay Liberation Front protest at the Examiner Building October 31, 1969. From the GLBT Historical Society. Shared in “From Stonewall to the White Horse: The Bay Area’s part in uprisings that changed the world,” Bay Area Reporter, June 26, 2019.

When the CHF attempted to have conversations with the editors of The San Francisco Examiner, they were kicked out of the building. The group organized a picket line outside of the Examiner building at 110 Fifth Street for noon on October 31, 1969. They published articles advertising the protest in underground newspapers, including the Berkeley Barb and Berkeley Tribe.

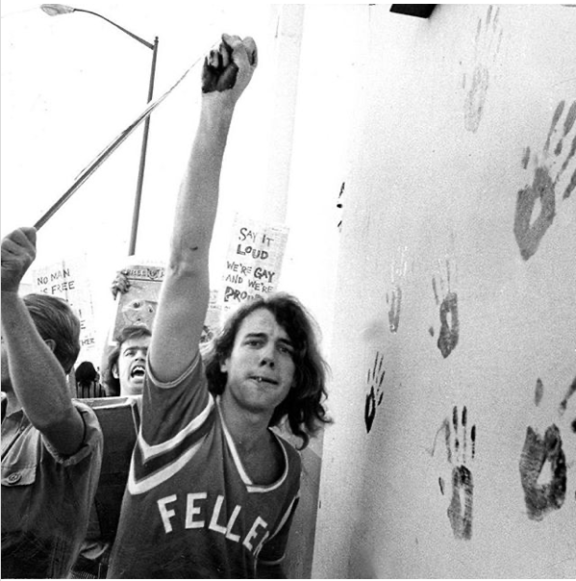

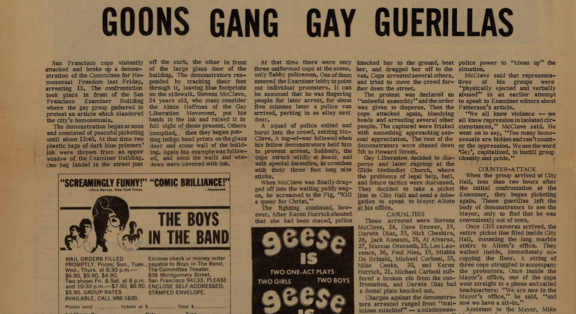

Around 12:40 pm, Employees from the newspaper dumped bags of ink onto the protesters. The protesters responded by coating their hands in the purple ink and marking the walls and glass of the front of the building. They were led by Stevens McClave, a leader in the Gay Liberation Movement.

“We all know violence — we all know repression in isolated circumstances,” [Stevens] McClave said. He went on to say, “Too many homosexuals are hidden and can’t counter the oppression. We use the word ‘Gay’, capitalized, to instill group identity and pride.” (1)

Police began harassing and arresting the protesters, seriously injuring some. In total, they arrested thirteen protesters, (including Berkeley Gay liberationist and journalist Leo E. Laurence), so the CHF left to regroup at the Glide Church. They began organizing a counter-protest at City Hall against the arrests. The initial plan was to send a small delegation to speak to San Francisco Mayor Joseph Alioto, but when the CHF learned that he was out of town, they entered the building up to the Mayor’s office.

The group of protesters organized their sit-in for three hours, until the building closed at 5:00pm, after which the police threatened arrest. Three individuals continued with the sit-in past closing, and they were arrested. Groups across the San Francisco Bay area organized for legal aid for the individuals arrested. John James wrote the next week in the San Fransisco Good Times about the efforts to help those arrested, demonstrating the power of the Committee for Homosexual Freedom.

“But the organization’s unusual decentralized structure had given it outstanding depth of leadership, and by Monday morning friendly contacts had been established with three candidates for Supervisor, top defense lawyers including Terence Hallinan who appeared in court Monday morning, several well-known clergymen, a friendly bondsman, and most of the straight and underground media in the Bay Area. Also over the weekend hundreds of dollars were raised and thousands of leaflets produced and distributed in gay bars in San Francisco and Oakland.” (2)

Months later, eight of the individuals arrested and charged with misdemeanors pleaded no-contest and were given six months probation.

Gay activists saw an opportunity to change the way the Gay community was represented in the dominant media of the period, which they saw as an important step towards liberation. Although there were some underground publications that offered a liberated Queer persepective and conservative Gay publications from SIR and the Daughters of Bilitis, radicals Gays wanted control over a publication of their own. Although the protest demonstrated solidarity between these movements, the divide between the more radical Gays and the “old order” continued.

“Within the organizations are strong factions supporting Marxian socialism, armed self-defense, and nonviolence. The issue of nonviolence vs. self-defense is an emotional one which could split CHF. By contrast, the older homosexual organizations, such as Society for Individual Rights (SIR), Mattachine Society, Tavern Guild, and Daughters of Bilitis, are non-political associations including conservatives, liberals, and many nonpolitical as well as radicals. They seldom if ever take part as organizations in demonstrations and they maintain a style of middle-class respectability, often calling themselves “homophile” instead of “homosexual” organizations (“homophile,” meaning working for equal rights for homosexuals, is avoided by CHF as not direct and open enough). A conflict developed between SIR and the new organizations over SIR’s tactical refusal to give organizational support to CIIF’s drive to place on next June’s ballot a proposition which if passed would officially commit the city of San Francisco to oppose discrimination against homosexuals. CHF also sent colorful picketers to oppose the annual Halloween Beaux Arts drag ball sponsored by the Tavern Guild. In the festive spirit of that occasion everyone was friendly, even the police. And there is little doubt that the old and new organizations can cooperate concerning what happened in the last week, despite all previous disagreements. Although members of CHF have called gay bars “walk-in closets,” referring to “closet queens” or homosexuals who hide their homosexuality, the picketing of the Examiner was protesting an article attacking gay bars and breakfast clubs.” (3)

However, this protest was a turning point for many involved in the Gay liberation movement, demonstrating the targeted violence of the police and the need for radical change.

(1) “Goons Gang Gay Guerrillas,” Berkeley Barb, November 7-13, 1969, 6.

(2) John James, “Out of the Bars and Into the Streets,” San Francisco Good Times, Volume 2, issue 43, 11/6/1969, 6, 7.

(3) John James, “Out of the Bars and Into the Streets,” San Francisco Good Times, Volume 2, issue 43, 11/6/1969, 6, 7.

Sources also consulted.

Sarah Hotchkiss, “Armed with Ink, 1960s Activists ‘Struck Back’ Against Homophobic Media,” KQED, July 13, 2019, https://www.kqed.org/arts/13859570/friday-purple-hand-gay-liberation-1969.

Tommi Avicolli Mecca, “Sometimes You Work With the Democrats, and Sometimes You Riot,” in Ten Years That Shook the City: San Francisco 1968-78, edited by Chris Carlsson (San Francisco: City Lights Foundation: 2011)

Marc Stein, “Guest Opinion: Recalling Purple Hands Protests of 1969,” The Bay Area Reporter, October 30, 2019, https://www.ebar.com/news/news//283715.