The construction of the Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) system was the brainchild of the Bay Area business elite, who sought to further integrate the regional economy and modernize its transportation system, then-heavily reliant on car-choked bridges and freeways. The proposal and construction of the system was not viewed as an unalloyed good by all Bay residents, however.

In particular, the construction of the West Oakland station became a lightning rod for neighborhood activists. The station stood to bisect the neighborhood’s Seventh Street business and entertainment district. Residents whose homes were slated for demolition often found themselves unable to afford to buy another house anywhere in the city with the meagre compensation offered by the transit agency, forcing them to rent or to leave altogether.

Moreover, employment discrimination was widespread among BART contractors, with many preferring to hire white workers from out-of-state than to hire local black jobseekers. In response to these twin crises of displacement and discrimination, a group of religious leaders, legal aid workers and community activists formed Justice on BART (JOBART), which focused on increased compensation for residents displaced by BART and an end to discriminatory hiring among BART contractors.

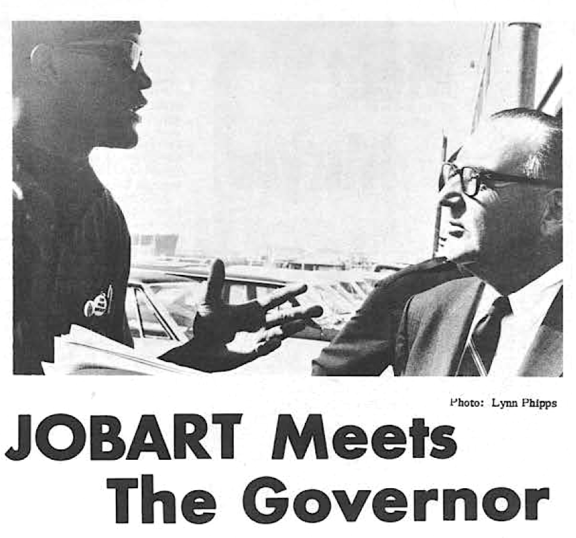

JOBART, like The Flatlands, arose out of a community organizing tradition that favored direct action, public confrontations with powerful. individuals and institutions. Thus, when Governor Pat Brown visited Oakland’s Jack London Square for the unveiling of BART’s new transbay tunnel, a group of JOBART demonstrators led by Flatlands contributor Curtis Lee Baker presented him with the group’s demands and criticized him for inaction on housing and unemployment issues.