(A scan of the full BWMC Songbook is available here)

In the liner notes of the Collective’s first album, Suzanne Shanbaum said, about “Fury”: “I wrote this while I was a repair technician for a large corporation. It was the first time I had a job that paid a lot of money. I thought that money and respectability would make me feel less powerless, but actually, all I gained was more bills and the realization that I could still be raped or arrested just as fast as before. I discovered power and respect in this system is not accessible to me no matter what I do. I realized that other women shared my experience and that together in our outrage we must take the power and turn things around for good.”

“I hope country women won’t take my line about farmland as a lack of support. I used to see moving to the country as a dropping out of the struggle because it wasn’t on the same front which I was fighting. I still feel it is important to resist, however I realize now the importance of struggling on every level in every place; learning to take power in every way.”

(The recording of “Fury” from The Berkeley Women’s Music Collective [1976])

***

In a recent interview, Shanbaum reflected on her songs “Thorazine” and “Fury,” and her history of writing songs about the oppression of women. She recounted how “Fury”—and the larger Berkeley Music Collective Songbook in which it appeared—led to trouble at the US-Canadian border crossing.

Suzanne: I was writing some about psychiatric assault. I have a song called “Thorazine” and I wrote some other songs dealing with depression, dealing with the oppression of women. How society thinks that you’re crazy because you’re not Sally housemaker.

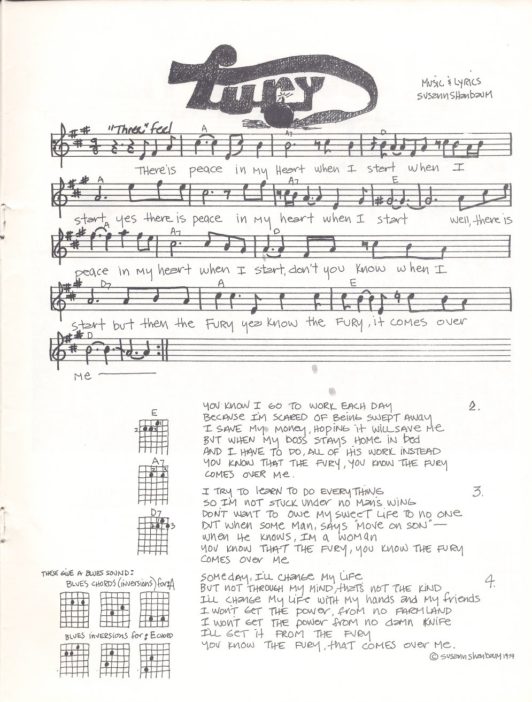

I wrote a song that’s called “The Fury.” The lyrics start, “There’s peace in my heart when I start, but then the fury comes over me.”

We published a songbook that included that song. One time we were driving to a gig in Canada and we got to the border and they said, “Why are you going to Canada?” And we really didn’t know what to say. We said, “Oh, well, we’re just cutting through Canada to get to this other place in the U.S.” We didn’t know if you need special paperwork to play in another country. Did we need a visa? We didn’t really worry about things like that until we were pulled over at the border.

They decided to make us take everything out of our van to inspect it. We never had this experience before. Sometimes the police somewhere would pull us over and say, “Oh, girls, hi, you got any boys hidden under there” and stuff like that, “Have a good day.” That was before the SLA.

The Symbionese Liberation Army kidnapped Patty Hearst and made her father give away food to poor people. That was a turning point. Women were in that organization and they were armed. After the SLA was in the news, authorities would not assume that we were harmless. They stopped us and would make us unload everything.

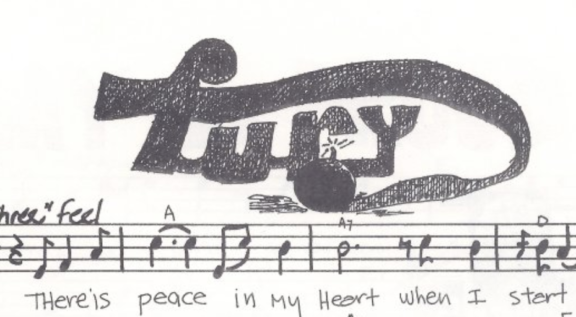

If you look at that song book on the page containing the song I wrote called “The Fury,” on the title, Vogl drew a little a cartoon bomb with a fuse. Like a bowling ball with a fuse sticking out, like a cartoon.

This freaked them out. A song named “The Fury” with a bomb. Everything came out of the car. They looked at every piece of equipment that we have and they say, “Well, you can’t bring this into Canada.” We’re like, “Why not?” They said, “Because you can sell it into Canada and you can’t do that.”

“We’re not going to sell it. We need it for our gigs.” We had to argue with them at the Canadian border forever. They were about ready to lock us up for having this contraband song, “The Fury”, about how your boss makes more money than you with a cartoon of a bomb. Finally we got out of there, it was a miracle. We went to a great gig on this Island in Canada, had a great time, and then came back to the U.S and they never put us through that again, but that was the songbook’s most famous moment.

***

In a recent interview with Debbie Lempke, she added onto the story:

Debbie: When we went to Canada, we’re trying to get into the country because we had some gigs in Canada, and they looked at our material and they looked at our songbook and they decided we were undesirables. And we had to carry papers, that said we were undesirables and put down a few thousand dollars, I think it was like close to $3000 or something like that, to ensure that we wouldn’t sell our equipment, that we would get back. It was like a bond or something as we traveled through the country.

And I don’t know how we raised that that quickly. I don’t think we had that much in cash. I don’t know how we did it. Somehow we got into the country, we were able to get through the border. I think they saw that one song that’s got a little bomb.