West Oakland was on the losing end of more than one urban renewal plan, but the construction of BART posed nearly an existential threat to the neighborhood.

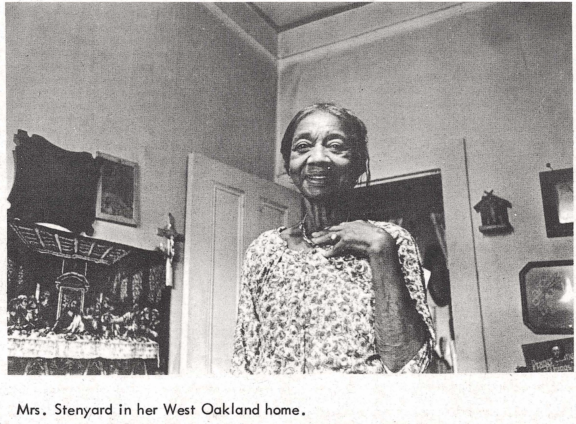

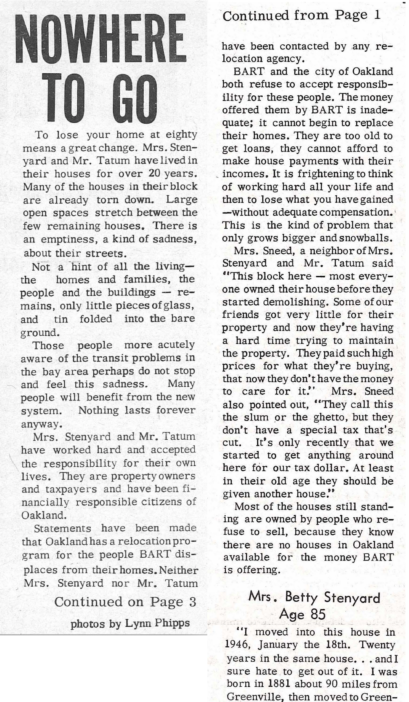

Plans for the neighborhood’s station proposed to destroy the viability of the city’s black entertainment and business district centered on 7th St, with the residential areas along its fringes on the chopping block as well. The Flatlands sought at every opportunity to dramatize and publicize the victims of the city’s structural injustices, and the subjects of this piece are manifestly sympathetic: Barclay Tatum and Betty Stenyard, elderly West Oakland residents of long standing whose houses have been targeted by BART.

Reflecting larger migratory patterns, Tatum and Stenyard both moved to their current homes in West Oakland during World War II, when black Americans from all over the country were migrating to the East Bay for jobs in the booming war industries. Stenyard had left an agricultural job in the Central Valley in 1946 to join her husband in Oakland, taking a job as a nurse at Oak Knoll Naval Hospital; Tatum, a 43-year veteran of the Naval Supply Center, Oakland, had been living on his pension for over a decade by the time his house was condemned.

As was typical for residents affected by BART construction, they were forced back into the rental market; neither Stenyard nor Tatum were offered market-rate compensation for the loss of their homes.

***

This piece from The Flatlands offers another example of how the newspaper used the power of photojournalism (here the work of Lynn Phipps) to capture the lives threatened by BART’s use of eminent domain.