The Elementary Secondary Education Act (ESEA), passed in 1965, was a cornerstone of Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty. Intended to redress the educational inequality wrought by a century of segregation and unequally-distributed resources, ESEA expanded federal funding for education for school districts that could prove that they were making progress on desegregation.

One measure for doing so, later undertaken by districts across the country, was busing: federal and local officials hoped that, by transferring black students from often-segregated neighborhood schools to previously-all-white schools, and vice versa, educational equity could be achieved. In Oakland (as the name of The Flatlands implies), segregation often broadly corresponded with the city’s geographical divide. Schools in the hills neighborhoods were disproportionately whiter and better-resourced than their counterparts in the flatlands, and dedication to this status quo by hills residents had stymied previous desegregation efforts.

With the looming threat of lost federal funding, Oakland schools in 1966 rolled out a modest busing proposal: 360 elementary students from three flatlands schools (Highland, Lockwood and Woodland, all in East Oakland) would be bussed (using ESEA funding) to under-enrolled schools in the hills.

ESEA officials pitched the program to parents and community members as a golden opportunity, not only for flatlands students but also for their new classmates in the hills. As Oakland ESEA director Andrew J. Viscovich put it, “How can a child at such a school [with no minority students] know who his constituents are, or what a cosmopolitan city means?” Black students would benefit from adequately-funded educational facilities and smaller class sizes; white students would have their world views expanded by exposure to black students.

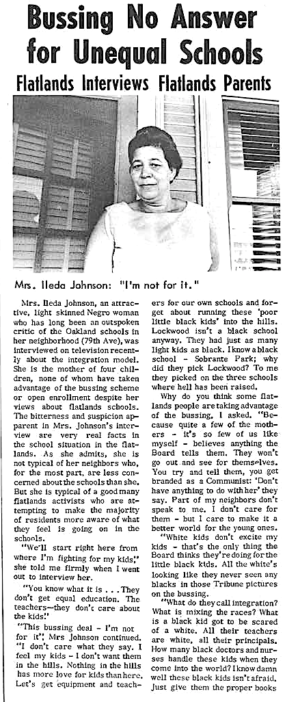

This notion, while attractive to progressive education officials, failed to assuage the concerns of black parents and students. The Flatlands, which often interviewed community members to seek their opinions on the hot-button issues of the day, conducted lengthy interviews with a number of parents whose children were eligible for the program and found that many of those interviewed had serious concerns.

For a start, the number of students eligible was widely considered inadequate in the face of overcrowding in the target schools; the construction of portable classrooms, a stop-gap measure at best, was encroaching on valuable playground space at these schools, and parents note that classrooms with 30-50 students were not uncommon, a state of affairs impossible to remedy with the transfer of fewer than 400 students. The lack of reciprocity in the program was also decried — why were children from the hills not also bused to flatlands schools? Why were only elementary students eligible for the program, when junior and senior high students faced the brunt of prejudicial disciplinary practices?

As these parents saw it, the program was well-intentioned but wholly inadequate to the problem at hand. The solution to Oakland’s educational inequality, in their minds, was simple yet unthinkable to the members of the Board of Education: the allocation of greater funding to flatlands schools, the hiring of black educators and administrative officials, and the revision of the district’s disciplinary practices. The paper notes that some parents are eager to take advantage of the possibilities inherent in the new program; the majority, however, continued to demand more.