The concept of this program was a simple one––to provide hungry children with food in the morning before they go to school. It was rightly called a Survival Program, because without its existence, children would certainly not thrive and in some cases may not have survived. This program helped to ensure that they did not have to make it until lunch without having enough food to sustain them, so that they could focus on what they were supposed to be doing in school—learning. The government was not providing breakfast for Black children who lived in poverty. Therefore, the Black Panther Party saw an opportunity to use its stature as an activist organization to make a measurable difference in the communities it aimed to represent. As one government official stated, “They are feeding more children than we are” (1). “They”––that is, the BPP––fed the children using private funding raised through community members, church groups, etc. The careful articulation of the various aspects of the program, how it worked, and what was required, down to the menu plans and nutritional mix, allowed the program to be easily replicated across the country, and it was.

A second benefit of the Breakfast for Schoolchildren Program was that it brought different generations together to interact in a meaningful and important way. Parents were asked to volunteer to make the program work, so they had a sense of ownership in the positive outcomes. In addition, they received training in how to plan and prepare nutritional meals that they could then use in the home. Parents had a chance to interact not only with their own children in the school environment, but also with neighborhood children, which cemented community unity. Meanwhile, adult males, many of whom had no connection to those being fed, were often charged with serving the breakfasts to the children, which gave them the opportunity to talk, establish relationships, and provide the children with a sense of being part of a larger, caring, and nurturing community. The significance of this cannot be overstated, because studies have shown the positive impact that responsible adult males can have in determining a child’s life outcomes and in supporting a family and a community as a whole (1). The idea behind the program was that as these children grew up, they would recognize their self-worth (2) and would then be more likely to engage in community involvement opportunities themselves to emulate the adult male figure in their life. They would be more likely to see men as nurturing and to understand the role that men could and should play in bringing children up, both in the household and in the community.

The success of this program led to many other Survival-type programs being created to serve other needs. The Free Food Program is one excellent example of offering a similar experience to help individuals and families in addition to schoolchildren. The lack of healthy and fresh food was shown to have an adverse effect on Black people’s well-being and to undermine their ability to work and be secure. The program served as an educational initiative as well, where nutritious food built not only the individuals’ bodies, but also the communities in which they lived. The political agenda of the BPP in founding the program is evident from their statements publicizing the program: “We want an end to the robbery by capitalists of our Black and oppressed communities” (3).

The seeding of a movement to change life outcomes for Blacks and other minorities in America started with Breakfast for Schoolchildren. From there, it burgeoned and grew to address a number of social ills and racial inequalities. It inspired other changes across the country and beyond, and it still stands as a symbol of what is possible with vision, leadership, and even modest well-leveraged resources.

References

Jennifer M. Threlfall, Kristen D. Seay, and Patricia L. Kohl, “The Parenting Role of African American Fathers in the Context of Urban Poverty,” Journal of Child Poverty 19, no. 1 (2014): 45-61. Accessed May 15, 2020. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3728162/

Morgan Vickers, “The Free Breakfast for Children Program and the Contestation of a Right to Food,” Black Power in American Memory, last modified April 18, 2017. http://blackpower.web.unc.edu/2017/04/the-free-breakfast-for-children-program-and-the-contestation-of-a-right-to-food/#_ftnref10

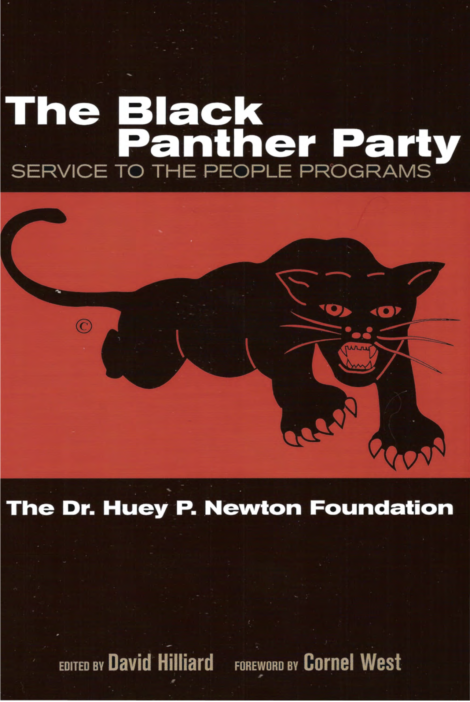

David Hilliard, The Black Panther Party: Service to the People Programs (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008).