In a special municipal election in 1972 that set the stage for the 1973 election, 71% of Berkeley voters turned out to vote down Amendment M, 37,890 to 26,599.

Amendment M pitted Berkeley’s center-right against its surging progressive coalition, which had been gaining seats in the City Council.

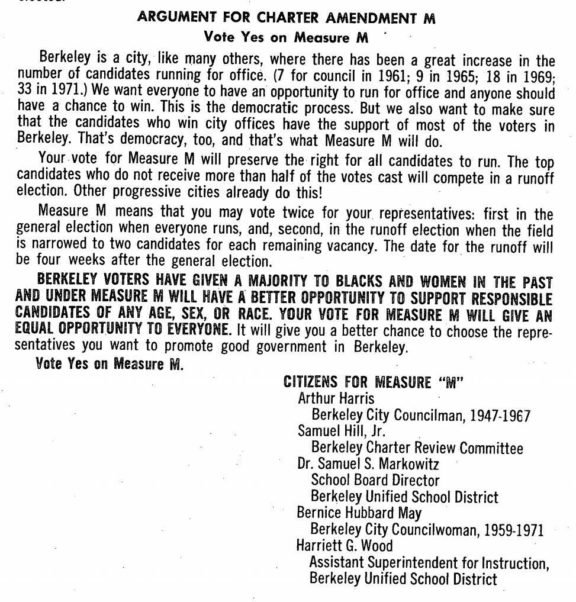

Amendment M proposed that there be two phases to every city election, the first open to all candidates and the second a runoff in which the top two candidates from the first election would compete head-to-head, an election process that has been proven to reduce the numbers of minorities and women who are voted into office. The argument for Amendment M claims — in a kind of dog-whistle politics — that the amendment is geared simply to allow democracy to function as intended, as a means for the majority to rule.

Lest this seemed too subtle, the argument in favor of the amendment then pulls back the curtain on the anxieties behind its formulation (in bold and all-caps): “BERKELEY VOTERS HAVE GIVEN A MAJORITY [OF CITY COUNCIL POSITIONS] TO BLACKS AND WOMEN IN THE PAST AND UNDER MEASURE M WILL HAVE A BETTER OPPORTUNITY TO SUPPORT RESPONSIBLE CANDIDATES OF ANY AGE, SEX, OR RACE. YOUR VOTE FOR MEASURE M WILL GIVE AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO EVERYONE.”

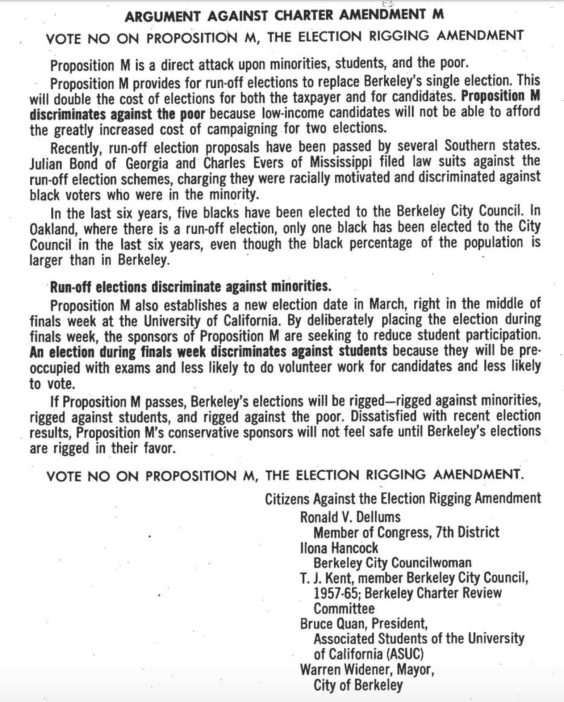

The argument against Amendment M was joined by local Congressman Ronald Dellums, the progressive Ilona Hancock, Berkeley’s new black mayor Warren Widener, and the head of Cal’s student government.

The failure of Amendment M would push the frustration of some Berkeleyans to center stage in the election of April 1973.