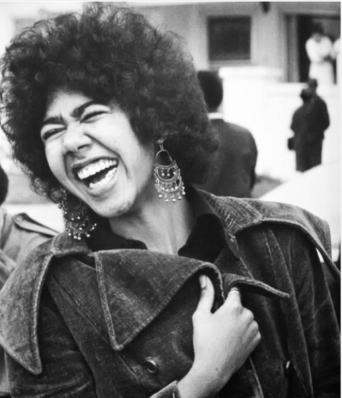

This oral history of Ericka Huggins covers her life from childhood to the 1970s, and centers on her work in the Black Panther Party. For the purposes of this project, only the excerpt of the oral history interview that is most pertinent to the Oakland Community School is included here. In this excerpt, Huggins describes “The Children’s House,” the Intercommunal Youth Institute, and her time as the director of the Oakland Community School from 1973 to 1981.

Before the Intercommunal Youth Institute, “The Children’s Houses” were two homes in North Oakland where children of Black Panther Party members would stay if their parents were travelling, out speaking for long periods of time, or political prisoners. The children were “educated there and slept there,” and lived communally, taken care of by a rotating staff of Party members. Later, they moved to a big house on 29th Ave in Fruitvale. The Intercommunal Youth Institute opened in 1971, and later changed its name to the Oakland Community School. Though this transition is not elaborated on in Huggins’ oral history, there are several documents about the Intercommunal Youth Institute included in this project that can provide further information.

Huggins’ oral history mentions the Children’s House and Intercommunal Youth Institute, but it provides the most insight into the culture, curriculum, and everyday operations of the Oakland Community School. Huggins recounts that the joy she derived from learning and teaching kept her going, as teachers were not paid, though the party subsidized their housing and food. She also says that the school’s culture was defined by family-like bonds and mutual respect between staff and students. Huggins states that “The Party always functioned on need. What do the people need? That was the consistent question. How can we serve the people? With the children, they were hungry. That wasn’t okay. That just wasn’t going to serve the purpose of this school.” Born out of this need, the school began to serve not only breakfast, but lunch and dinner as well. Feeding the students fresh, healthy food was one element of how OCS sought to care for the whole child.

The curriculum of OCS consisted of subjects such as math, reading, and writing, that one would find in any school. However, at OCS, the underlying principles “Don’t give them your bullshit and your horrific experiences in life, but tell them the truth, and talk to them” were embedded in the curriculum. Furthermore, students were encouraged to investigate, question, and learn through experience. For example, when teaching about slavery, OCS students simulated being in a slave ship and asked many questions such as “So how did they pee, Ericka? Where’d they poop” “Did they get sick? Did they throw up? How did they have babies? Do you think they wanted to live?” Children were allowed to think through difficult history without it being sanitized for them. However, Ericka is sure to mention that though they discussed these topics, they did not “agonize over them for days.”

Children at OCS also meditated every day (a practice that Huggins developed while imprisoned) and participated in activities such as dance, song, and poetry writing. Additionally, Huggins makes clear that at OCS, students were not encouraged to “get their education and get out.” Instead, their homes and communities were consistently affirmed by the school, and students were encouraged to both “live the life of their dreams,” and give back to their communities.

Later, she describes how Huey Newton’s drug use and instability, driven by the FBI’s COINTELPRO operation, negatively affected the Oakland Community School’s students and finances. Huggins describes her experience of these changes, saying: “I spoke up about it one day when he came and sat in my office and was talking to me. The assistant director of the school, Donna Howell, was there. I said, ‘Huey, your behavior, which I know is partly caused by the pressures you’re experiencing, is having a negative impact on the school and the children, and you’re using the money that comes into the school for yourself.’ You have to understand that he had never done that before. The school was sacred to him. So I knew that the drugs were taking him right over the edge. He said, ‘Say one more thing and I’ll knock your teeth down your throat.’ […] He didn’t touch me but I knew at that moment, I can tell you what I knew: The Huey I knew was gone. Gone. As a matter of fact, there was a time not too long after that that I looked into his eyes and I don’t know who was there, but it wasn’t Huey” (95).

Huggins recounts that she was repeatedly raped by Newton. He threatened that if she told anyone he would hurt her children. In the oral history, her explanation of her decision to leave the party was edited out, but in another section, she says that her “inner and outer life depended on it” but that “leaving the school and leaving Mark [her partner] were the two hardest things, the school because of the children” (101). Though it doesn’t directly pertain to the school, it seems important to include Ericka Huggins’ reflections on her relationship with Huey Newton: “The thing about Huey Newton is this: he was a good man too. So how I remember him is for the good things that he did do. I don’t choose to remember him as a horrible person because I feel like we all have demons, and I don’t excuse a person for the things that they do, operating from their demons, I don’t mean that, but I don’t hold anybody in place, because I don’t want to be held in place either. We all can transform” (103).

Overall, Ericka Huggins’ oral history gives incredible insight into every part of this project, from the Children’s House through the final years of the Oakland Community School.