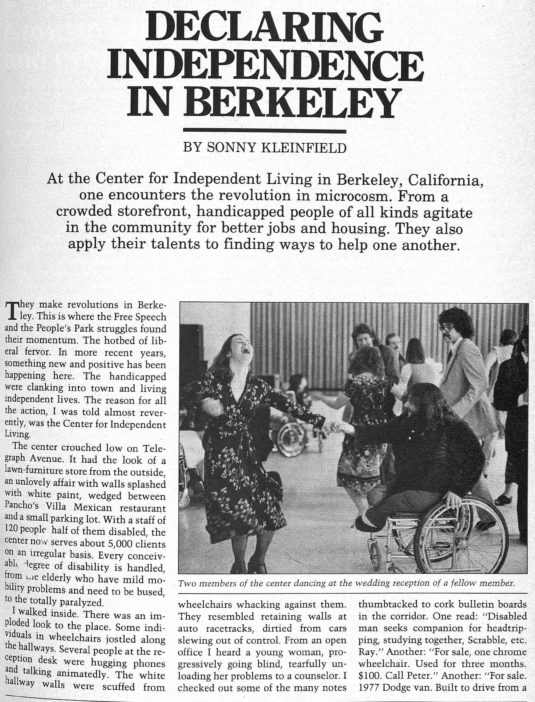

“They make revolutions in Berkeley….[S]omething new and positive has been happening here. The handicapped are clanking into town and living independent lives. The reason for the action, I was told almost reverently, was the Center for Independent Living.”

By the end of the 1970s, the successes of Berkeley’s independent living movement and civil rights demonstrations had reached national acclaim. In 1977, people with disabilities and allies took over the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare’s San Francisco office for twenty-five days, making it the longest sit-in ever recorded in history. Activists demanded that Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973 be implemented, which would guarantee civil rights protection for people with disabilities. The sit-in brought together cross-disability coalitions of folks advocating for their rights with civil rights advocacy organizations, like the Black Panthers, who delivered food and supplies to those inside.

In this excerpt from his book The Hidden Minority: America’s Handicapped, journalist Sonny Kleinfield paints a colorful picture of the crip mecca that was Berkeley. He provides a rich history of the independent living movement’s origins, from the consciousness raising at Cowell Hospital, to funding the PDSP with monies from the Office of Health, Education and Welfare, to the surge non-student consumers going to PDDSP for services, and finally the creation of the CIL in 1972. We also learn some of the drawbacks of Berkeley’s reputation as America’s crip capital. As people flocked to Berkeley, there was simply not enough accessible housing and the CIL was having difficulty keeping up with demand. The CIL’s staff members often put disabilities up in their own homes when hotels turned these new band of migrants away.

On page 76, Kleinfield cites the CIL’s concerted attack on the removal of architectural barriers and improving transportation access—Hale Zukas’ forte. After Berkeley’s streets became relatively wheelchair accessible, their focus shifted to sidewalks in Oakland, in addition to making AC Transit and BART accessible. Accessibility didn’t materialize over night and required numerous lawsuits by CIL or numerous planned demonstrations by advocates.

***

Below please find the second page of this article; for the full article, click on the link to the right.