This British hour-long documentary, narrated by Rosalie Wilkins, aims to capture the story of the American disability rights movement.

It begins with the observation that, for a disabled visitor to America, Berkeley—”the crips capital of the world”—is “the place where you will feel immediately at ease.” It stitches together interviews with Ed Roberts, Judy Heumann, Rolf Hotchkiss, Debbie Kaplan, Ron Washington, Kitty Cone, and others to develop a portrait of the disability rights movement from the 1960s to the early 1980s. The documentary features substantial footage of the 25-day “Section 504” sit-in at San Francisco’s federal building, along with extensive commentary on it.

It ends with trenchant coverage of how, under the Reagan Administration, the many gains of the disability rights movement were threatened. Under Reagan’s proposed budget, social services were targeted to be slashed — and services for people with disabilities were on the chopping block. On camera Ed Roberts observes that, with the Reagan era, people with disabilities had entered a “real traumatic time.”

The last scene features Wilkins visiting the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C., and suggests how the American disability rights movement inspired people abroad to advocate for people with disabilities: Wilkins herself became a notable disability rights activist and, as a member of the British House of Lords, a prominent policy maker shaping disability rights in the UK.

***

The full transcript (courtesy of Minnesota’s Council on Developmental Disabilities) is below.

***

[music]

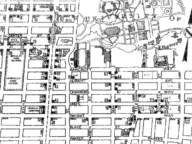

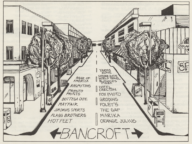

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: If you are a disabled visitor to America, and especially if you get to California, Berkeley is the place where you will feel immediately at ease. People don’t stare or deliberately not stare. You’re just taken for granted, and you soon begin to realize why Berkeley has been called the crips capital of the world. Berkeley’s always been known as a place where movements for social change have begun, but in the more conservative and relaxed atmosphere of the 1980s, it’s hard to remember the scenes of violent confrontation which were typical in the’60s when students on the Berkeley campus were rioting against the Vietnam War and campaigning for the rights of minorities.

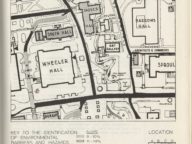

It was in that atmosphere of protest that disabled people began to realize that they, too, were a minority which would have to fight for its civil rights, and so a movement was born. Today, wheelchairs are a commonplace sight on the campus, but 20 years ago, it was very different. So what was it like to be a disabled student at Berkeley in the early ’60s?

Rosalie Wilkins: Well, to start with, you’d have been living in a hospital unit, treated as a medical problem and, apart from going to your classes, that’s where you would have stayed. There was no possibility for taking part in ordinary student life. But as the radical movement flowered, a group of these severely disabled students decided to break out and they called themselves The Rolling Quads.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: The leader of the Rolling Quads was Ed Roberts, paralyzed by polio when he was 14.

Ed Roberts: I was the only disabled student on the campus. It was very weird, I was stared at all the time. It was very clear that they didn’t want me there. In the beginning, they were afraid I might die or something serious might happen to me. Once we convinced the university that I could go there, they couldn’t reject me because of… I had high grades but we couldn’t find a place to live, and we finally found a student health center that I could live in. And I was very much, you know, a bullet student academic and doing well until I began to realize how difficult it was for me to get around the campus and some of the awful attitudes there were on the part of professors. And I think because they started with me and I was very severely disabled and had an iron lung, they were willing to take anybody after that.

All right – a breakthrough. Thank you. Bye-bye.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: For Ed, each bad experience was a further spur to his determination not to be restricted by his disability, and before long, he was to be joined by other disabled students with the same ambitions.

Ed Roberts: Within three or four years, there were about 12 of us. We really began to feel that we were fighting for our own independence and that there was a future for us out in the community. But we had to think really through how to do it. How were we going to make ourselves free?

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: At about the same time, across the country in Chicago, Eunice Fiorito, blinded at 16, realized that she, too, had a fight on her hands if she wanted an equal chance in life. Eunice was to become the first president of the American Coalition of Citizens with Disabilities

Eunice Fiorito: I was a bouncy kid who liked life, and I was concerned about how I was going to live that life. But on the other hand, I was very much certain that I was, and I was going to master it

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Today, Eunice Fiorito is an advisor on disability in the Department of Health and Human Services in Washington.

Eunice Fiorito: I finished college in about three years. I say that to you only because it was my vocational counselor’s position that, in fact, I wasn’t ever going to get through college and I was going to, if you will, be out of school and not have a degree within three years. And so I was very delighted when in three years I could walk to his office and say, “I have this degree and you were wrong.” That began to make me aware of how people with disabilities were going to be treated by society. And then I tried to get a job as a teacher in the state of Illinois. And one must consider that this is now back 20 years or better ago. And the state of Illinois said, “No, you can’t teach. You are blind. You can’t handle children and how will they react to you anyhow?” That was the next piece, and I started to hunt for a job and I couldn’t get a job. That then brought to me an awareness of the unfairness, the way people were being discriminated against.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Judy Heumann was in the forefront of the rights movement in New York in the’60s. She’s now Deputy Director of the Center for Independent Living in Berkeley, begun by Ed Roberts and now a model for similar centers across America.

Judy Heumann: CIL is an organization which is run by persons with various kinds of disabilities – physical disabilities, blindness, deafness, persons with mental retardation. We have a long history of wanting to not only provide direct services for people but also to be able to begin to influence policymakers so that they could understand more clearly those policy barriers which prohibit us from being integrated within the community.

For myself personally I became really actively involved in the movement after I had been through a struggle of getting education and continuing to have this image of the American Dream – if I worked hard at school and if I really studied and if I did everything that I was told to do, I would be able to go out and then get a job, and I would be able to be, you know, be Miss Middle Class America living in suburbia if I wished to do that. But in reality what happened was every step of the way was a real struggle. And even once I had gotten through university and gotten my degree to teach, I was then discriminated against specifically because of my disability. So at some point within me, I had to acknowledge the fact that no matter how hard I worked, I was still not viewed as an equal person, and if I could accept not being viewed as an equal person, then I could kind of slide away into the background, but I couldn’t accept that for myself.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: What did you do about it?

Judy Heumann: Well I… I began working a lot with other disabled people. I had for a number of years been friends with disabled people, but we hadn’t been as political as we became. And what happened over the last 10 years in this country is that disabled people have begun to band much more closely together to form what I would define as the movement.

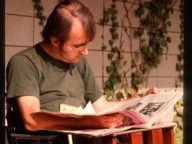

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Ralf Hotchkiss, who designs wheelchairs, and his wife Debbie Kaplan, a civil rights lawyer, became involved in the Disability Movement in Washington in the early ’70s.

Ralf Hotchkiss: When I first became disabled, now 15 years ago, I got involved right away in the technology of disability. I was a bicycle maker and I…and I almost had to fix my wheelchair first weekend out, but I didn’t get involved in politics for another five years afterwards. Then I was working for Ralph Nader in auto safety and all these disabled people started writing him letters, and he asked me to find out what was going on. I did. I met Judy Heumann, who you must have talked to by now, and got involved in some of the early demonstrations, setting them up in Washington, D.C.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Can you tell me about those early demonstrations? What part did you both take?

Ralf Hotchkiss: Debbie wasn’t disabled yet.

Debbie Kaplan: I was just becoming disabled at that point in California. I was at…a year out of college. I had a diving accident and broke my neck, and found myself in the world of disabled people. But I remember the first thing I wanted to do when I was in the rehabilitation hospital was to find out from other disabled people what the world was really like for people with disabilities. How people functioned on the outside. What it was that made some people have independent lifestyles. And the hospital really didn’t do much to provide that. And one of the groups that came to visit us was a group of the people who originated the Center for Independent Living called the Rolling Quads, and it was through people like that who were strong role models for me in my identity as a person with a disability that really got me involved.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: The movement had now begun to coalesce as disabled people all over America decided that they had to take action and demand access to buildings and transport and education. They wanted jobs, housing, and adequate funding and services to get them out of institutions. They wanted the equal opportunity which they believed was their right under the American Constitution and a fighting chance to prove themselves as useful members of society.

Ed Roberts: I started in the Civil Rights Movement. I started working with Black and Chicano civil rights, and somehow in the middle of that, when things were going very well, I stopped and said, “What am I doing here? I’ve learned all these great organizing skills and I should be working with my own people.”

And that was the transition. We realized we could do it ourselves, that we needed some support, that we needed to make the social systems like the welfare system that paid for our attendants and basic support. That had to work for us, not against us. So we had to…that way we had to get involved with the state legislature to change the rules and regulations, and to change the laws so that it promoted independence rather than maintenance and dependence

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: In 1975, Ed Roberts became Director of California’s Department of Rehabilitation, serving over 100,000 disabled people.

Ed Roberts: One of the conditions that I took, that, you know, the Director of Rehabilitation, was that I would have the freedom to be the advocate and to be out front on issues that even the governor and the administration may not agree with me on, but that I had to have that freedom to be the out-front advocate in this movement. And that I couldn’t be limited by some archaic notion of what it means to be a director of a large agency.

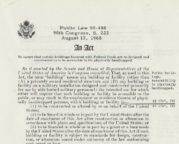

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Ed’s department has a budget of 150 million dollars and a staff of over 2000. Over the years, the concept of rehabilitation has changed from finding jobs for physically handicapped people to a positive policy of nondiscrimination aimed at integration for all handicapped people. That policy was enshrined in the Rehabilitation Act introduced during the Nixon administration in 1972.

Eunice Fiorito: The Rehabilitation Act was a most progressive piece of legislation when reviewed at the time and would have opened many doors for our independence. The administration in 1972, however, I believe, and so did many other disabled people believe, that this administration felt that the piece of legislation that was then being proposed, which then included programs of independent living, what they called advocacy, client advocacy programs for people to exercise their right to get what they felt that they were justly deserving of in order to be functional citizens, were much too progressive, and President Nixon at that time vetoed the bill. We then felt, and I think we were ready to realize that we had to take command of our own lives and become political.

Judy Heumann: When the Rehab Act was vetoed by President Nixon, it was done, oh, about a week and a few days before the ’72 elections with Nixon and McGovern, and a group of us from Disabled in Action and a number of other organizations decided that we wanted to do something publicly about it. So we organized within, oh, not many days a demonstration which started out in Manhattan at what was called the Federal Building. We had never been there before and we took like, I don’t know, 60 or 80 people up to this Federal Building. And when we got up there, it was like in the middle of no place. It was on this little island, and we had this demonstration and we had these great flyers and we had this symbolic funeral of disabled people being killed by the Nixon administration. And the next thing we knew, out came these city police. They drove up in this car. They asked who the leader was and people sent them over to me. And the guy said to me, “Do you know that you’re trespassing on federal property?” And I said, “Yes,” and he said, “Are you going to leave?” And I said, “No,” and we expected the world to end, and he said, “So stay,” and he turned around and he walked away.

So we decided we weren’t making the impact that we wanted to, so we were going to sit down in the street and we were going to stop traffic. So we did. We all went out into the… Most of us went out into the street. But, as I said, there were like hardly any cars coming by. So we all got into our vans and into the cars, and there we traipsed off to Madison Avenue, which in Manhattan is like…it’s a huge street. And we got out of the cars and we decided that what we were going to do is we were going to sit down in the street. So at 4:30 in the afternoon we formed this huge circle. We cut off four streets, but that was too scary because there were only 60 or 80 of us and there were huge trucks and cars. I mean, you know, Manhattan is like a crazy city in the best of times. And so we decided that we would retreat, we would only go onto one street, but still we shut the whole city down. They were announcing, “Paraplegics stop traffic in Manhattan,” and the police went and got a representative from Nixon headquarters and they wanted to know what we wanted. We said we wanted a public debate with the president on national TV to debate why he had vetoed the Rehab Act. The guy thought we were totally crazy. He just walked away going, “You’re crazy, you’re crazy.”

Ralf Hotchkiss: That was one of the biggest was when Nixon did veto the Rehab Act. On one of the snowiest days in Washington’s history, many people, over a hundred, I believe, came down from New York City in buses and basically stormed the capital, visited all their congressmen and all the all the congressmen who had voted against it and built up enough support so that I believe that was the strongest congressional override in history, override of a presidential veto.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Finally, on September the 23rd, 1973, Nixon signed. The Rehabilitation Act was now law, but there was yet another hurdle to be overcome.

Eunice Fiorito: In this country, when a law is passed, there must be followed, then, regulations, which really explain the law and set forth the actual policy and the practices of how that policy is going to be interpreted. Well, that did not come about, particularly within Section 504.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Section 504 states, “No otherwise qualified handicapped individual in the United States shall solely by reason of his handicap be excluded from the participation in, be denied the benefits of, or be subjected to discrimination under any program or activity receiving Federal financial assistance.”

Eunice Fiorito: It was 1975 and there were no regulations. And we proceeded then to come into 1976, and there were still no regulations and, therefore, the law was not being implemented.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: January 1977, a new president in the White House, but instead of new hope, yet more frustration as Jimmy Carter’s administration delayed the regulations yet again.

Eunice Fiorito: Within two days after the new Carter administration was put into place, about 15 of us came to see then Secretary Califano, stating the issue about the regulations not having been issued and expressing our concern and desire to work with him and his staff to get them out within a reasonable period of time, particularly since they had been circulated, people had studied them, they had commented, etc., etc.

That process then started all over again. The administration decided they wanted to review them and they wanted to study them, and we went back and forth to meeting after meeting after meeting in good faith. And we finally said to them, “Look, we have had enough. From a legal point of view, these regulations seem to have been quite good. You’ve studied them a lot and we’ve studied them. If you cannot come up with a decision, we must then take action.” And we gave them until the 4th of April. And on the 4th of April of 1977, they did not have the regulations ready for issuance. And so we had developed an alternate plan, and that plan was to bring our plight to the attention of the people of this country.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: The key part of the plan was to take over federal government office buildings across the USA, and in the full spotlight of press and TV attention, Judy Heumann expressed the deeply felt frustration of the disabled minority.

Judy Heumann: The harassment, the lack of equity that has been provided for disabled individuals that now is even being discussed by the administration is so intolerable that I can’t quite put it into words. I can tell you that every time you raise issues of separate but equal, the outrage of disabled individuals across this country is going to continue. It is going to be ignited. There will be more takeovers of buildings until finally, maybe, you begin to understand our position. We will no longer allow the government to opp…oppress disabled individuals. We want the law enforced. We want no more segregation. We will accept no more discussion of segregation. And I would appreciate it if you would stop shaking your head in agreement when I don’t think you understand what we are talking about.

Applause

Jeff Moyer singing: Civil rights were knocking at our door. But Carter wouldn’t stand on 504. Keep your eyes on the prize…

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: The sit-ins to demand the signing of the regulations which would enforce the Rehabilitation Act took place in federal buildings in 10 cities across the United States. In Washington, the demonstrators moved in determined to stay. The government officials refused to allow any food or drink into the building and, in effect, starved them out. In most cases, the sit-ins lasted only a few hours, but in San Francisco, the demonstrators stayed and stayed. They were not going to go away.

Jeff Moyer singing: Hold on, hold on.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: Three-and-a-half years later, we took Judy Heumann back to the Health, Education and Welfare Building where over 150 disabled people held out for 28 days. With her came three people who had shared the experience, Kitty Cohen and Ron Washington, fellow workers from CIL, and Jeff Moyer, who’s blind and who became the resident musician for the demonstrators. For all of them, it was the first time they had returned since 1977 and the memories were still vivid of the day when they moved in, a strange, ill-assorted, but unique army.

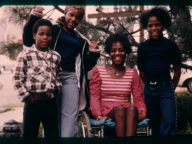

Judy Heumann: In 1977, one of the beauties of the demonstration was the fact that we had persons with all kinds of disabilities and all age ranges. There were people who were blind and people who were deaf and people were in wheelchairs. They were quadriplegics and paraplegics and people who were blind and in wheelchairs, and people who were deaf and in wheelchairs. And you just think of the kind of disability that you would want to think of, and there was someone there that was representing that constituency.

Jeff Moyer singing: Hold On. Hold on. Hold on. Keep your eyes on that prize. Keep your eyes on that prize. Keep your eyes on that prize. Hold on.

Ed Roberts: That my ability to regain a pride in myself as a person with a disability is one of the most important things that’s coming out of what’s happening here today. And to see hundreds of people with disabilities rolling, signing, using canes, the more severely retarded people for the first time joining us in this incredible struggle, is one that leads me to believe that we’re going to win this. That we are not going to stop until 504, which I believe is a basic civil rights platform, the platform that guarantees to each person with a disability in this county, that they are equal in the eyes of the law and that they will have equal access to educational institutions, to hospitals, to the institutions in our society which serve us all.

Various people talking: And here we are. Inside. I just want to pass real fast through here. It’s going to be easier this time. This was our very first headquarters. Remember how we… It looks quite the same. Gee, it looks the same. Remember that desk? Really. Do you remember how we used to use the phones at that desk. Calling all over the country… It was the first thing we did. [overspeaking] I remember crashing out on the couch. Should we answer the phone? It looks like they’ve got a new typewriter, must be a computerized one. Yeah, I remember people used to spend the night on that couch. They used to have a TV in here. Remember, we monitored all the media?

Demonstrator: It’s the first step in a long march. We’ve got a long way to go, but we’re on the way and we’re united. There’s never been a group of people so connected to each other as this group of people here, and we’re ready to walk together, march together, wheel together. Find our way down the road toward real civil rights.

Demonstrator: I want California to sign 504 for many, many different reasons. One of the reasons is our deaf people want to work. We don’t want to live on SSI if we can work.

Ron Washington: I was really angry when I came in because we had been meeting and there was a lot of things in the newspaper about the 504 regulations possibly being cut, some of the important things that we felt were meaningful for us as disabled people were going to be taken out. And so when I got up here, I was really very angry and wanted to… I felt that we could… There were so many of us, so many disabled people, that we could probably get some changes done right then.

Judy Heumann: There was a total sense of power and control, and when the director was sitting in the chair where Jeff is now, there was like so many of us and he knew nothing and we kept… Remember we kept asking him to bring up the people from Higher Education and the people from the different parts of the Health, Education and Welfare Agency who were supposed to know about the regulations. And they came up… and two guys came in and said, “What’s 504?”

Kitty Cone: It was amazing because all the demonstrators had just been preparing and organizing for weeks in advance and had just come from a really militant rally, and we all knew what we were talking about. We knew real specifically what 504 was and what was happening, and they just didn’t know at all. And here they were, in charge of our civil rights. It was… They must have been astounded. I mean, they must have been just…

Ron Washington: They were shaking in their pants because…

Kitty Cone: Oh, they were. They were scared

Ron Washington: Yeah. As you said, we had that really powerful rally outside that just gave… I know, gave me a lot of inspiration and strength and I felt like I was Popeye and was ready to move this desk and jump on it. Poor Mr… What was his name, Maninata?

[Maninata]

Ron Washington: He was, you know, he just really hadn’t… And the people that came up also, they were just really stupid and…and.

Judy Heumann: I remember getting really furious the longer that we sat in the room. You know, there was a demonstration outside where it was like very exciting and very powerful, and then when we made it into the building, to me, it was also an incredible sense of control because we’d moved all of these people up through the elevators up onto this floor. And while there were a few of us, you know, who were planning to potentially stay overnight, the more I sat in this room and got these answers from people or these absolutely non-answers, the angrier I got. And that’s when people started really feeling like we couldn’t leave because no one knew what we were talking about, but we knew that they were trying to rescind the regulations.

Ron Washington: I know, Judy, you said…”You’re going to sit in, aren’t you?” I said, “Well, Judy, I didn’t come prepared.” She said, “You… You gotta stay here, Ron. You gotta stay here.”

Kitty Cone: To me, it was… There were so many things to be proud of. The fact that we managed to sustain ourselves for 28 days. We were so organized. I mean, we had our press committee, our food committee, our medical committee. Here we were, some of us severely disabled, sleeping on the floor every day, not knowing if we were going to get arrested, and going to bed at 3 o’clock in the morning and getting up at 6 o’clock, having clean-up committees so that the workers could come in and carry on their work in the building, and managing to tackle incredible political issues and refute the government when they were coming out with lies.

Demonstrator: t really wasn’t an outlaw act. We were trying to make the system work, the typical 90-day period for regulations stretching to three-and-a-half years, and after all the public input looking like they were going to pass what they wanted to anyway in terms of water-downed regulations, it made everyone feel like it was… And it was a very righteous cause.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: They were not to be denied their victory. At the end of April 1977, after the longest sit-in in US history, it was over. The government capitulated and signed the regulations.

Demonstrators: Power to the people! Power to the people! Power to the people! Power to the people! Power to the people!

Eunice Fiorito: 1977 was the year in which disabled people had a great deal of visibility. They come into their own as a minority group in the minds and the eyes of the people and the administration of this country. But more important, to themselves, to disabled people, they felt a strength. An inner strength, I think, developed from the success as well as from the struggle.

Woman: Can you open the elevator please?

Intercom voice: It’s right there. The doors did not open?

Woman: They just opened, thank you.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: In the next few years, many of the barriers to integration began to go down. Disabled people were coming off welfare and into jobs, moving around, mixing in the outside world as equals, but, of course, society was not transformed overnight. There were continuing battles to be fought, especially over the question of mass transport where the costs of making the system accessible are so high. In some cities like Washington, Seattle, and San Francisco, it was starting to happen, but resistance by the transport companies grew. Kitty Cohen recalls the struggle to get the San Francisco Bay area bus company to conform to the law.

Kitty Cone: It was a hard fight. We had to go into court two times suing AC Transit. We attended all their board meetings. We participated in their studies. We went to public hearings where we would bring 50 disabled people who would testify quite eloquently about their personal experiences. We, at one time, about 200 disabled people demonstrated against AC Transit and blocked their buses at commute hour. And, finally, I think they realized that they were up against a force that simply would not subside, and so they adopted a policy of full accessibility. And since that time, they have really made an effort to make the system work, and I think it’s working really well. We’re really proud of what’s happened here.

Jeff Moyer singing: The civil rights were knocking at our door. But Carter wouldn’t stand on 504. Keep your eyes the prize, hold on. Hold on, hold on. Keep your eyes on that prize, hold on.

Rosalie Wilkins: With it all behind them, disabled people were feeling confident and hopeful as the ’70s drew to a close. But in 1980, as Reagan rode to victory on a campaign promising to cut taxes, bring down inflation, and reduce government spending, the fear began to grow that rights were something the politicians would hand out in the good times and abandon when it suited them. The question disabled people were facing was: Would the struggle have to start all over again? The question that all affluent societies must face was confronting the American people: How much do you care?

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: At his inauguration on the 20th of January in 1981, President Reagan promised the American people a new beginning that sounded a grim note of warning on public spending.

President Ronald Reagan: For decades, we have piled deficit upon deficit, mortgaging our future and our children’s future for the temporary convenience of the present. To continue this long trend is to guarantee tremendous social, cultural, political, and economic upheavals. You and I as individuals can by borrowing live beyond our means but for only a limited period of time. Why then, should we think that collectively as a nation we’re not bound by that same limitation? We must act today in order to preserve tomorrow. And let there be no misunderstanding, we’re going to begin to act beginning today.

Rosalie Wilkins: On May the 7th this year, Congress was due to vote on President Reagan’s budget proposals. The harsh reality of his commitment to slashing government spending on social programs while pouring money into defense. The future for disabled programs looked bleak, not only money but the hard-won legislation was at stake. So on that day, disabled Americans from all over the states gathered on Capital Hill to remind their Congress that the equal society for disabled Americans was in jeopardy.

Public speaker: We are here because we believe that disabilities or handicapping conditions in no way and by no means lessen, negate or destroy our rights.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: The first Reagan budget proposed cut federal funding for social services by 25%, but the crucial issue was the decision that money for social programs would be handed over to each state on block and without strings. Effectively, this would remove the federal government’s power to direct how money is spent and would thus weaken the Section 504 legislation, which relies on having the weight of a federal mandate for its enforcement.

Public speaker: Let’s agree to do everything we possibly can to keep block grants from passing this Congress. At least that way, we’ll have still some control over the programs that help handicapped people. I’ll work with you. I’ll disseminate any information you give me. I’ll do everything I can, and I assure you every other liberal member of Congress will do the same, but we need more than that. We need the Republicans, we need the conservatives, and you’re the folks out there that can get them. So let’s all work together. Let’s at least make sure that whatever money comes through, is directed to specific programs and not block grants. Thank you very much.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: During the rally, small groups of demonstrators from each state formed delegations and moved into the Senate buildings to lobby the Senators and Congressmen who were supposed to represent their interests. Judy and her friends from CIL sought the help of Congressman George Miller of California, a Democrat.

Congressman George Miller : I don’t think anybody ought to mislead you. I think that it has already been outlined and as it will be implemented, it’s going to fall disproportionately on your community, on the handicapped community, on the elderly and on the poor. It’s just very clear that that’s where it has to fall because there’s other areas of the economy of our society have been reserved not to participate in those…in those cuts. And I think what we will find out now is that it’s far more harsh than they have led people to believe.

Ann and I have been going over just the cuts in our area, and you can’t achieve in the Education and Labor budget, you can’t achieve what the president wants to achieve without repealing the Handicapped for Education Children’s Act, but he hasn’t told that to the parents or to the handicapped students that that’s how he has to achieve his goal.

As a matter of fact, he hasn’t even told that to the Congress yet. He has quietly submitted that legislation for concern. You can’t achieve the kinds of cuts that he desires without outright repeal of many of these programs because certainly we’re not going to participate in cutting programs to the extent where they become so inefficient they serve no one. And I think they know that. I think it’s clear. I really don’t know where you find 11 billion dollars this year in cuts in the Education and Labor budget.

But very shortly, after the vote is taken here in the next 40-45 minutes, that’s going to be our mandate on Monday to start searching for those funds. I know the announcement today that Dave Stockman is struggling to find another 5-10 billion dollars in cuts because he told us interest rates were going do down, right? Well, interest rates went up over the last four or five days. And so the cuts are going to become more severe because they still believe in a Margaret Thatcher syndrome that this is how you work your way out of your problem.

Well, they’ll also find out that there are limits to the tolerance of people in this country. I think that people are going to have to become more militant. I think as you said, you’ve hit the streets before and we’ve had tremendous victories. [Buzzer sound] And there goes the call to go vote on this matter.

But I think that you’re going to have to go those legislators who have voted for these budget cuts and hold their feet to the fire. I think you’re going to have to go around the country and tell people in their community what the result is because there’s a great belief in politics that somehow you can escape the ramifications of your actions. And I think you’ve got to make it very clear that you can’t do that this time, that the results are too severe and too harsh.

Rosalie Wilkins: Thank you.

Congressman George Miller: Thank you. I’m sorry you had to come all this way for this reason. You know, it wasn’t too long ago you made this trek so we could implement the laws. And now you’re here three years later trying to say don’t repeal them. It’s amazing how it works in this system. Thank you. Thank you.

Rosalie Wilkins: Thank you.

Congressman George Miller: Bye then. See you. Good bye.

Public speaker: There are a lot of selfish people in the Congress of the United States who will do whatever they can to cut programs that are important. So it seems to me the mission that you need to perform and we need to perform is to identify those individual members who are the great budget cutters and see what we can do either to change them or cut them out of the Congress as members of the House and Senate. [Applause] So don’t let your work end when you get off the plane, train, bus or car and get back home. Continue to work to build public sentiment directing it at those individuals that you have a power and an opportunity to affect in one way or another. Above all, do not be discouraged by whatever may happen today. And I can tell you, out of my 40 years of experience in the nation’s capital, much of it in that building behind us and in these buildings beside us, I can tell you that sometimes the darkest hour is the time when if the people get sufficiently aroused, they can win what seemed like a lost cause. I thank you.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: I asked Republican Senator Lowell Weicker, who’d voted against the block grants, if the administration was aware of the effect of its policies on disabled people.

Senator Lowell Weicker: No, I don’t think the administration has assessed the effects of any of its cuts in the social programs. I think they just wanted to achieve a bottom line dollar amount. There was no evaluation of either what was good and what was bad. A good example of that would be education. Education where we know statistically for every dollar the federal government’s put up, we receive some 9 dollars back in return in the sense of that person being a productive member of society earning larger wages, being taxed more, etc. We get much more back than we put out.

Rosalie Wilkins: Do you think there is a backlash amongst the America public against the demands being made by handicapped people?

Senator Lowell Weicker: I think there’s a backlash in this country at anything that doesn’t fit into a majority status, whether we’re talking about the minority which is racial, the minority which is sex, the minority which is disabled and retarded. All of this means trouble, and the majority doesn’t want to be troubled right now.

Judy Heumann: What’s being proposed in this country is we’re going to balance the budget. But if you analyze the budget, you see that quite the contrary is true, that they’re taking about 36 billion dollars out of social services programs, but they’re not putting it back into the people’s hands, they’re putting it into the military budget. So I think that, if anything, the Civil Rights movement have been becoming too weak and that we should be much more forthright and much more strong.

Ed Roberts: I’m convinced that we’re going to go through a real traumatic time right now and, just as President Reagan is challenging these rights, I think that’s going to go on for a while because there’s, unfortunately, when we talk about integration with blacks and changing the schools, we didn’t talk about how much it cost. It costs billions and billions of dollars. But when we talk about equal rights for the handicapped, we’re talking about billions and billions of dollars and the cost issue has become the forefront issue. Not whether we should have basic rights. I think everybody agrees that that should happen, but the cost becomes the hang-up.

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: What tactics do you think disabled people should use against Reagan’s budget cuts?

Ed Roberts: Everything we can think of, especially that are theatrical and that help remind people of our basic values in this country are. That we do care about those folks that are considered the weakest and that government does have a role to play with people who aren’t going to make it without some kind of government help, whether it’s maintenance kinds of help or movement toward independent living. I think constantly reminding people that while we’re in an age and a shortage of dollars, that we can’t lose our human values and the values that we built this country on.

Debbie Kaplan: I think it will come out that the public is fairly supportive even though… I just heard a recent public opinion poll that 80% of the people in the country are not in favor of what Reagan is doing in social service cuts. I think people are fairly supportive once they understand what we’re talking about, once they understand that we’re talking about access to jobs and access to living independent lives, and we’re not talking about just handouts.

Ralf Hotchkiss: All along some of our strongest support has come from the far right anyway. Self-determination, independence, those are all both left and right issues. And I don’t think that we’ll lose on all fronts

Narrator Rosalie Wilkins: You don’t feel that civil rights is becoming a dirty word at all.

Ralf Hotchkiss: No.

Debbie Kaplan: Disabled people are not going to go away, and the increased education, the increased rights that disabled people have are going to lead to more and more disabled people who will want to partake in society and not be treated like little children all their lives. And one way or another sooner or later it’s going to happen.

Senator Lowell Weicker: Now none of this comes cheap. Who’s arguing that? I’m not going to sit here and say that, you know, that we can have these things and we’re going to cut taxes. But what I am saying is that the purpose of government, it seems to me, is not… It’s not in our officialty like a corporation. Government is there to help each individual flower to his or her greatest extent, to give expression, you know, to what they are or what’s inside of them. Because government is the people. And yet in what we’re doing now either cutting back on funding or once again shifting the problem back to where the problem originated, you know, I think we’re washing our hands of this matter for political purposes so that the majority…so that the majority can lead their lives unencumbered by the problems of others or the cost that those problems raise.

Ed Roberts: I think that the difference between now and 20 years ago is that the movement of the disabled is concerned about all of this and has a fundamental belief that we all can take our places in the community and we don’t have to be institutionalized or segregated. If you come from a basic spirit that you believe you can succeed, and that mixes in a lot of philosophies, you know, like positive mental attitude and all the different things that crop up around this country, they are definitely ingredients in what happened in Berkeley and what’s happening in the whole movement in this country. It’s like the people who are considered the absolute weakest in our society, we’re beginning to discover that we’re among the strongest in our own ways, that disability is very challenging and it can send you down in flames or it can send you up

Jeff Moyer singing: The civil rights were knocking at our door. But Carter wouldn’t stand on 504. Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on. Hold on. Hold on. Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on. Well after four years of delay, we reclaimed the ground we gained. Keep your eyes on the prize, hold on. Hold on. Hold on.

Public speaker: Some philosopher once said that if you can go to a country and just look at one or two things and make a judgment, on that country probably the thing that you’d want to do is to see how that civilization or that country takes care of its older citizens. Well, there’s some partial truth in that, but I would broaden that test just a bit to say that you ought to judge a country on how they treat their older citizens and their children and those who are disadvantaged.

Jeff Moyer singing: Hold on. Hold on. Keep your eyes on that prize. Keep your eyes on that prize. Keep your eyes on that prize, hold on.