Threads of Rebellion

“Happiness is feeling springtime.”

— Motto of Berkeley's Red Square Dress Shop

The world of fashion tends to move quickly, but did conventions around fashion ever change as quickly as in the five years after the Summer of Love? In 1968 many formal institutions still demanded women wear skirts or dresses; no woman had ever worn pants in the US Congress. But by 1971, popular brands like Levi were advertising jeans and corduroys to men and women alike—and in 1972 that same Congress passed a law declaring that public schools could not require girls to wear skirts.

The Bay Area was at the very center of this cultural makeover, as a group of designers embraced the task of dressing themselves and their customers for the new era being born. It was a fashion revolution with many different accents. For Berkeley dressmaker Liane Chu, that revolution meant the freedom to wear a simple slip dress, leave her long hair unstyled, and abandon wearing shoes entirely. For Bay Area-based Jeanne Rose, who became renowned as a designer of countercultural clothes, it meant wearing a blue velvet brocade pantsuit to a restaurant that wouldn’t seat women in pants. For their customers and clients, it was part of a broader invitation to make their world a stage.

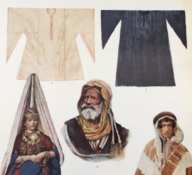

Fashioning the Counterculture: Borrowing and Breaking Free

Bedouin images from a pattern and costume book that Berkeley’s Liane Chu used for design inspiration

Young people affiliated with the counterculture wanted to make, through their forms of dress, something new and completely their own. Distinguishing themselves from the straight, white-dominated mainstream, hippies drew upon visual culture of the past, the international, and the “far out.” Young people in the Bay Area especially took religious and visual inspiration from historical Eastern European dress, Asian cultures, and Native American culture.

At the time, this borrowing was done in a spirit of admiration: what they wore suggested their refusal to conform to a culture they found oppressive and exclusive, and they conveyed this refusal through a vibrant array of forms, colors and textures. If there was a common thread behind this borrowing—a borrowing that we might now call cultural appropriation—it was the desire to communicate an open-mindedness: open-mindedness to new lifestyles, new forms of community, new ideas of how to be.

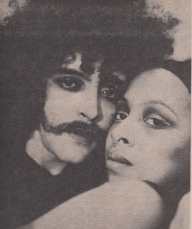

Glad Rags: Playing with Gender and Sexuality

One facet of this open-mindedness was an acceptance of deviations from norms of gender and sexuality.

If the magazines and ads of mainstream culture suggested that men should have short hair and women should wear skirts, the hippies and the freaks of the Bay Area threw the rule book out the window. They refused to be put in a sharply defined category, simply based on the gender or sexuality they were perceived to be. Liane Chu—then a prospective student to Cal—remembered being enchanted by the long-haired and sandal-wearing male students of Berkeley when she toured the campus; her parents, meanwhile, were appalled. The generation gap was often exposed at these sorts of moments, when old styles of performing “maleness” and “femaleness” came up for question.

Gender bending: from a Rags article on men wearing makeup (photograph by Kevin Higgins)

In the pages of Rags, a San Francisco-based magazine devoted to countercultural fashion, writers encouraged Bay Area youth not to feel confined by their gender when it came to getting dressed. Articles like “What Gay Women Wear” broke down, and tried to get past, the narrow stereotypes of how certain groups were expected to dress. There was a sense that, through gender role-play, straight society might be shaken to its core. “One unisexual person, a boy in makeup is more revolutionary than any bombing“: so wrote the author of a 1971 Rags piece on men wearing makeup. The language of “revolution” expressed the hope that gender-bending was much more than a vehicle for freedom of expression. With the right touch and on the right person, a little mascara and glitter could remake the world.

Introducing Jeanne Rose and Liane Chu

Jeanne Rose and Liane Chu—two important figures in late-1960s Bay Area fashion—were carried forward by the desire to create something new. Both took part in the DIY feeling of the era: they didn’t intend to be fashion designers and neither were formally trained. Yet, through their tenacity and imagination, both were able to create successful bespoke clothing enterprises, recognizing that there was a need for a departure from the binding garments that defined women’s clothing in their mothers’ generation.

Freed from the garters, the girdles and the other trappings of proper women’s dress, Chu made bespoke clothing for those “who wanted something a little different.” Meanwhile Rose made bespoke clothing for her child, San Francisco rockstars, and herself, inspired by a similar spirit of freedom from convention: she “never felt compelled to be like anybody else,” she said.

Men were no strangers to this newfound sense of freedom either. They didn’t stop at simply growing their hair out long, but also felt free to go underwear-free beneath their cords, jeans, and flowy pants: if one scans the photographs and footage from the battle over People’s Park, one is struck by the fact that many of these men —bending over to lay sod or load a wheelbarrow — left their underwear at home.

Fashioning the San Francisco Rock scene: Jeanne Rose

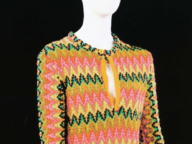

Jeanne Rose, modeling her own “fog suit” in 1966

Though the “Bay Area” is spoken about collectively, models for revolutionary fashion differed between Berkeley and San Francisco. In San Francisco, trends in clothing were deeply intertwined with the music scene, and the influential designer Jeanne Rose tied these two realms together. Though she resisted calling herself a “hippie” at the time, she was a nonconformist in her day, breaking down barriers and exploring new realms of thought as she led a split life between Big Sur and San Francisco.

Jeanne Rose’s brand was influenced by a variety of life experiences. Maintaining a life in Big Sur allowed her to stay connected to nature. A gifted student, she graduated from San Jose State University with a degree in zoology that earned her a spot at the University of Miami Marine Laboratory studying Marine Ecology. This background would later inform her commitment to all-natural fibers like silk, linen and cotton, and helped make her the self-possessed woman who created and wore the clothes she wanted.

Many other people wanted them too—Rose’s designs, that is. Starting out by making clothing for her daughter in a cabin in Big Sur, she gained notoriety after dressing members of psychedelic-folk band The New Age for a major concert in San Francisco. She then made eye-catching bespoke clothing for members of bands that defined and popularized the San Francisco psychedelic rock scene, including Jefferson Airplane and Big Brother & The Holding Company. Besides making custom pieces for Janis Joplin, Peter Albin and Jorma Kaukonen among others, she made beautiful pieces in paisleys and natural fibers, often decorated with gold braid, to be carried by local boutiques in San Francisco and Berkeley.

Fashioning the Berkeley alternative: Liane Chu

(photograph by Nacio Jan Brown)

Liane Chu of Berkeley offered another model for clothing making, informed by a distinctly “politico” sensibility. While working at a dress shop during her time as a Cal undergraduate student, she realized she was being underpaid. So she simply started her own dress shop a couple doors down on Telegraph Avenue.

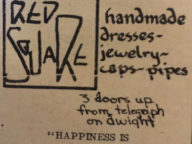

Red Square, ‘handmade clothes’: detail of 1969 photograph by Clay Geerdes (courtesy of Clay Geerdes estate)

The Red Square Dress Shop was more than just a bespoke clothing store; Chu saw it as a place that could involve the Berkeley community, and she drew folks in by taking in clothing and jewelry on consignment. The homemade sign out front—with its clenched fist on one side and an opulently costumed Eastern European woman on the reverse—announced both the political leanings of the owners, Chu and Michael Delacour, as well as the internationally-influenced clothing within. The store’s motto—“happiness is feeling springtime”—carried likewise the spirit of hope and renewal.

A politically active place to begin with, Berkeley developed a sense of fashion that was the product of an attention to political and social movements worldwide. In discussing how fashion was changing at the time, Chu spoke of admiration for the Black Panther Party, the French student protests, and an overall “appreciation for other cultures and American Indians and what they can contribute to our knowledge of how to live in the world.” Chu and her peers dressed in a way to let people see that “you were open to knowing that there were other possibilities.”

In her time working at the Red Square Dress Shop, Liane Chu remembers the popularity of a variety of Asian textiles that she bought in Chinatown. Wearing tunics, monk’s cloth, and vibrant international prints allowed members of the counterculture to underline, visually, their commitment to the practice of Yoga or the tenets of Hindu religion, for example.

According to Chu, the knowledge of alternative lifestyles freed the Berkeley politicos to say to themselves, “Let’s break out of this mold, let’s try something new, let’s grow our hair long, let’s have sex, let’s not shave… you know… let’s stop wearing makeup, let’s not wear bras. All of that! Let’s not put up with segregation, let’s not have war, let’s try new ways of living together.”

Starting the Red Square was a “let’s trying something new” moment. It was the product of a particular moment—the project of Chu and her boyfriend at the time, Michael Delacour, working harmoniously, hacking it in the shared-apartment-turned-shop, and gathering together a community around DIY fashion and countercultural idealism. But after three years, their relationship ended, and Chu—a rolling stone at heart—didn’t feel compelled to stay. The shop had lost its special sense of community to her, and she moved on.

The Two Paths Countercultural Fashion Took: Clothing Made “By Hand,” and by Monsanto

So what came out of the hippie fashion movement? The answer to that question takes us down two very different paths.

On the one hand, the local, the natural and the rebellious spirit lived on among the small boutiques and the custom made. Hippies and rockstars continued to make a statement in one-of-a-kind clothing from Jeanne Rose as she designed under the label Jeanne Colon. Later in life, Rose maintained an interest in all things natural and making products that bring people closer to nature through her aromatherapy business New Age Creations. Liane Chu’s legacy of making diverse and colorful handmade clothes lived on through “By Hand,” the fittingly named cooperative that took over The Red Square.

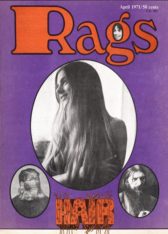

The “Hair” issue of Rags (April 1971)

On the other hand, the very localized movement of hippie fashion was co-opted by the mainstream for commercial purposes. The San Francisco-based fashion magazine Rags featured advertisements from major corporations as early as 1971, and companies such as Levi’s and even Monsanto, the agribusiness giant, jumped on the hippie bandwagon.

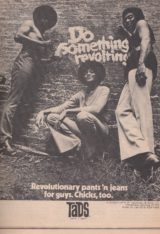

These major companies tried to use slogans crafted with countercultural lingo to sell mass-produced hip threads: an ad for Tads jeans asked the reader to “Do Something Revolting,” using three young, lanky and attractive black people wielding a spray can to make the appeal. Monsanto could be found hawking a “Truth and Soul” line of clothes, made out of “100% Acrilan acrylic.” The hippie look had caught on, so much so that it was profitable to mainstream clothing companies and even large multinational corporations.

All of which raised an uncomfortable question: what happens when a movement formed out of nonconformity becomes a popular trend to which many conform, and to which large corporations cater?

All of which raised an uncomfortable question: what happens when a movement formed out of nonconformity becomes a popular trend to which many conform, and to which large corporations cater?

Threads of the Tribe: The Search for Non-Western Styles

While we might view, with skepticism, how corporations like Mansanto quickly moved to co-opt countercultural values like “truth and soul,” we might also consider with another sort of skepticism how, in the search for “liberated threads,” many turned to non-Western styles for inspiration.

Alienated by what the underground San Francisco Oracle called the “linear or perpendicular” Western understanding of life, many members of the counterculture looked to Hindu and Native American religions and practices to find purpose. And their threads reflected this re-orientation.

Hippies striving for a sense of freedom and a close relationship with the land adopted certain aspects of Native American tribal dress—part of a longstanding white fascination with “playing Indian” that historian Philip Deloria has described in his landmark book of that title. Given that many of these hippies and youth in the Bay Area scene were white and part of the racially dominant culture, they walked a fine line between admiration and appropriation.

Notably, it was often white writers who explained, to a larger countercultural audience, the meaning of the Native American culture behind this style of dress.

A single article from a special issue of the San Francisco Oracle, dedicated to “the American Indian,” embodies this tension. According to Oracle editor Allen Cohen, “Sunbear Speaks” was provided by “an Indian medicine man who had begun teaching white youth the Shamanism of the American Indian.” But in its formatting, the piece presented Sunbear as, well, an oracle rather than a person with a specific history, tribal affiliation, and grounding in the world: he was valued precisely for seeming to stand outside history. Not coincidentally perhaps, Sunbear also found himself quoted, formatted and situated by a predominantly white editorial staff.

There was a danger, then, when young white people, living in cities like San Francisco or Berkeley, donned indigenously-influenced leatherwork to harken back to a more harmonious relationship with the earth. In some cases, they may have grabbed onto a culture perceived as outside themselves and then taken from it—as critic Greg Tate has written about white appropriation of black styles—”everything but the burden.”

Assessing the Fate of the Fashion Revolution

While it’s true that the visual culture and the slang of the hippie movement became folded into mainstream American culture, it’s equally true that the full complexity of the counterculture—its social activism, its interest in other cultures, its imagination of new forms of community and intimacy—was not so easy to reduce or boil down. The new, and often ragged, forms of social life that grew out of the streets, parks and concert venues of the Bay Area were far from fully conveyed, for example, in the famous 1971 Coca Cola ad where young people from around the world, many in hippie fashions, gathered on an Italian hilltop to sing about love and harmony — all with the goal of praising of Coke as “the real thing.”

In fact, one way of understanding the quick rise of countercultural fashion is that it tapped into a deep disenchantment, among young people, with the slick commercialization of the “American way of life”. The clothing spoke to a mood of disaffiliation, and a need to express in positive form the freedom that could be born from dropping out of the great American rat race.

In interviews, both Jeanne Rose and Liane Chu spoke to their sense of themselves as free spirits, guided either by a desire to experiment or to find a new path. “I’m like a leaf in the wind. I’m willing to float around and experiment,” said Rose. “People wanted to be perceived as the vanguard—like we’re ahead of you guys. We’re not straight like you guys are. It was a kind of arrogance, really, but a pride as well,” said Chu.

The mainstream did indeed race to keep up with this fashion vanguard, marketing the trappings of the hippie generation to a broader audience. But there was an important difference between those who simply bought hippie culture “off the rack,” as it were, and those who gave themselves to the deeper experiment and exploration that the counterculture, at its best, elicited.

Looking back, Chu had a pungent way of describing those who received their dose of hippie culture, say, by purchasing flared Levis from a glossy ad in a magazine. They “lived through the sixties,” she said, “but they didn’t.”

— Sarah Kersting

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Liane Chu and Jeanne Rose for sitting down with me and telling me their stories. Their firsthand accounts and powerful memories painted a vivid picture of life in the Bay Area at the time. I extend my gratitude to Tom Dalzell and Susan Schweik , who helped me understand the greater historical context for these developments in fashion. Special thanks to Tom for his Quirky Berkeley piece on Liane Chu which did much to inspire this larger project. This project wouldn’t be here today without their help as well as the invaluable help and comments from my classmates and our professor, Scott Saul.

Further Reading

Jill D’Alessandro et al, eds., Summer of Love: Art, Fashion, and Rock and Roll (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2017).

Philip Deloria, Playing Indian (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1997).

Tanisha Ford, Liberated Threads: Black Women, Style, and the Global Politics of Soul (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017).

Thomas Frank, The Conquest of Cool: Business Culture, Counterculture, and the Rise of Hip Consumerism (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1997).

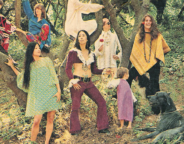

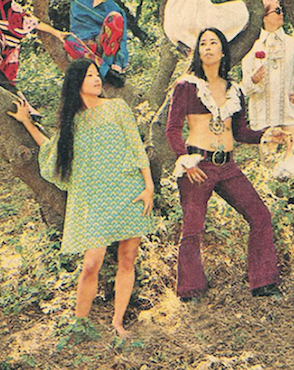

Clothing designers Liane Chu and Jeanne Rose, modeling clothes and jewelry designed by Rose in a 1967 photo shoot (San Francisco Chronicle)