The Integral Urban House

“Most environmental 'education' consists of an afternoon at the zoo or a wildflower walk. Here, environmental education is geared toward getting people to apply sound ecological concepts to their own lives.”

— IUH manager Tom Javits

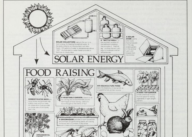

Founded in Berkeley in 1974, the Integral Urban House (IUH) was an experiment in domestic self-reliance and production-centered city living. It addressed increasing American frustration with environmental pollution and industrialized food production. From its composting toilet and solar-powered water heater to its bee hives, rabbit pens, and vegetable gardens, the IUH offered an ecologically sustainable model of “urban homesteading” and an alternative to the middle-class dream home.

For three decades, suburban single-family homes — built on former agricultural lands at the city’s edge — had served as engines of a postwar consumer economy and as symbols of prosperity and comfort.

The Integral Urban House modeled an opposing set of ideals and asked a different set of questions: How could a home help its residents live responsibly and ecologically, respecting the finitude of the earth’s resources? What would a household look like as a site of urban food and energy production rather than a suburban platform for conspicuous mass consumption? How might adaptive reuse reclaim decaying older homes for new use rather than bulldozing them in urban redevelopment schemes?

The Integral Urban House: from “back to the land” to “back to the city”

The counterculture ‘back-to-the-land’ movement of the late-’60s sparked fresh experiments in alternative living and collective household structure. Frustrated with mainstream politics and consumerism, a generation of young, largely white, often college-educated youths moved out to the countryside to experience life in communes and renewed connection with nature. Through trial-and-error learning, communards developed agrarian skills that informed an ethos of ecosystem custodianship.

But the back-to-the-land movement was also escapist, evading responsibility for reforming the nation’s ecological crisis at its source. On the Berkeley campus of the University of California, a team of students and young faculty members would attempt to transplant communal modes of ecological living into an urban context. They were the forerunners of what became dubbed the “back-to-the-city movement”.

In the 1971-72 school year, Sim Van der Ryn and Carl Anthony of the Department of Architecture, along with graduate student Jim Campe, devised a design studio course called “Making a Place in the Country – The Outlaw Builder’s Studio.” It brought undergraduates to forested land that Van der Ryn had purchased in Marin County adjacent to the Point Reyes National Seashore. There, they studied ecological principles on site and acquired practical construction skills. By the end of the academic year, they had built a village of communal facilities and small sleeping shelters from salvaged lumber.

A subsequent design studio, offered by Van der Ryn and Campe during the 1972-73 school year through the Department of Architecture, further explored what they called “Whole Systems Design.” Using patterns found in nature and building performance data, the student and faculty team investigated mechanical and biological systems that could support a dwelling low in resource consumption and minimally dependent upon large-scale energy suppliers. When the instructors were unable to find a textbook for their pioneering sustainable design course, the first class assignment was to assemble journal articles to create a course reader titled The Natural Energy Handbook. So many people wanted copies that the class bound and sold them to raise money for its final group project, a scaffold-like installation called The Energy Pavilion.

Built of salvaged timber and bristling with low-tech devices, The Energy Pavilion demonstrated the suite of innovative systems that would comprise the utility core of an ecologically sustainable passive solar home. Opened to the public just as the OPEC energy crisis had angry drivers lining up at gas stations across the country, it produced its own long line of visitors, their curiosity piqued by local television news coverage.

Built of salvaged timber and bristling with low-tech devices, The Energy Pavilion demonstrated the suite of innovative systems that would comprise the utility core of an ecologically sustainable passive solar home. Opened to the public just as the OPEC energy crisis had angry drivers lining up at gas stations across the country, it produced its own long line of visitors, their curiosity piqued by local television news coverage.

The Farallones Institute: The “Integral” Team Assembles

Van der Ryn’s rising profile prompted meetings with like-minded architects, engineers, and biologists to discuss how sustainable design might offer ways to reconnect with natural systems and live in more satisfying ways. They partnered to form the Farallones Institute, a non-profit organization focused on urban homesteading and energy autonomy.

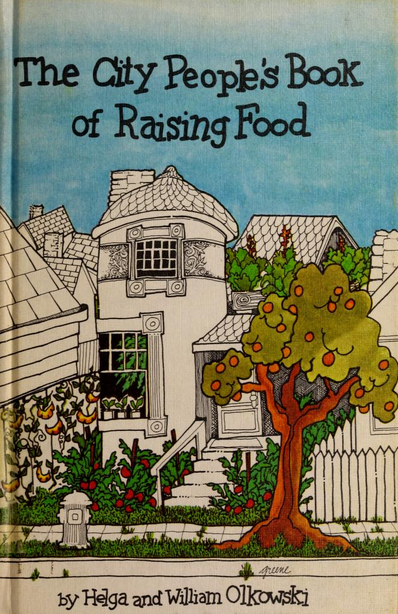

Key figures of the Farallones Institute included Bill and Helga Olkowski, an entomologist-biologist power couple who were devoted environmental activists. Known locally for growing organic produce in their own backyard, they taught university classes on urban food production. Having written a how-to manual titled The City People’s Book of Raising Food and having created pest management programs in Berkeley and San Jose, they brought invaluable experience to this facet of the project, along with a range of connections to both the university and the larger surrounding community. Bill Olkowski helped form the first recycling center and curbside pickup program in the US, the Ecology Center in Berkeley. Helga Olkowski helped found Antioch College West, an alternative college in San Francisco focused on landscape design and ecosystem management.

Key figures of the Farallones Institute included Bill and Helga Olkowski, an entomologist-biologist power couple who were devoted environmental activists. Known locally for growing organic produce in their own backyard, they taught university classes on urban food production. Having written a how-to manual titled The City People’s Book of Raising Food and having created pest management programs in Berkeley and San Jose, they brought invaluable experience to this facet of the project, along with a range of connections to both the university and the larger surrounding community. Bill Olkowski helped form the first recycling center and curbside pickup program in the US, the Ecology Center in Berkeley. Helga Olkowski helped found Antioch College West, an alternative college in San Francisco focused on landscape design and ecosystem management.

The Olkowskis also brought connections to Cal — connections that would serve them well as they recruited students for the project. Bill worked as an Assistant Research Entomologist and Helga as a Research Associate for the Agricultural Experiment Station, and they taught classes and helped form a now-popular undergraduate class called ESPM 117, Urban Garden Ecosystems.

Other participants in the Farallones Institute included Sterling Bunnell, a psychiatrist and naturalist who taught at the California College of Arts and Crafts, and Art Boerike, a carpenter and photographer who documented the handbuilt dwellings of Bay Area “outlaw builders.” With the Institute, this new group of people embarked on a new, interdisciplinary project on healthy, holistic life in the city. This was the seed of the “Integral Urban House” project.

Why “Integral”? For the Farallones Institute, the word meant both “together” and “essential,” evoking the “integration of ideas about structure as both habitat and life-support system.” “Integral” also marked a conscious departure from the term “self-sufficiency.” Because planetary systems and processes are so thoroughly interconnected, Institute participants concluded that no one truly could be self-sufficient. Instead, they focused on the pursuit of “self-reliance” through optimized use of available resources to create a better life.

An early photo of the Integral Urban House (Jim Campe)

The building that would become the Integral Urban House was a dilapidated Victorian cottage most recently used by the City of Berkeley as a drug rehab center. It was adjacent to a stretch of mixed run-down industrial buildings and low-income, predominantly Black residences that had been targeted by the city for redevelopment. Within a block of a neighborhood undergoing processes of “urban renewal” through the displacement of residents and the demolition of older structures, the cottage at 1516 Fifth Street showcased the alternative of retaining historic buildings and investing in their adaptive reuse.

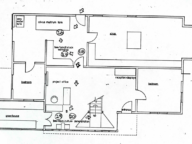

Inside the Victorian: Home Is Where The … Composting Toilet Is?

The Farallones Institute purchased the house for less than $10,000 and quickly got to work renovating the structure using recycled timber. Junk yards and dumps were scavenged for useful material. Insulation was installed to retain heat from passive solar collectors. Nothing was wasted, upholding an ethos of sustainability through reuse.

The construction of a backyard vegetable garden and a freshwater pond promised a first harvest of produce and fish by the time residents moved in. Lettuce, tomatoes, spring onions, kale, and fruit trees were some of the first crops planted. A beehive, chicken coop, and rabbit pen to provide honey, eggs, meat, and manure fertilizer completed the edible landscape.

Helga and William Olkowski, at work in the garden of the Integral Urban House

More technologically ambitious projects included a composting toilet, the Swedish “Clivus Multrum,” installed below the house to produce nutrient-rich compost from human and vegetable waste through a carefully controlled process of aerobic decomposition. Greywater was collected in a catchment system to water the garden. Solar collectors flanked the southern face of the house, absorbing energy to generate hot water and electricity.

The goal was to inject ecological consciousness and energy efficiency into the routines of domestic life. To break from the paradigm established by the consumption-oriented suburban home, the Institute created an opposing model home that reduced dependency on external inputs with domestic equipment and habits devoted to processes of production and the reduction of waste.

Environmental Education for the Community

As a “living laboratory,” the Integral Urban House was more than a site of experiments in sustainable design. It was also a public showcase for systems and practices of urban self-reliance that never before had been attempted at such a scale and in such detail. Unlike back-to-the-land counterculture communes, the IUH served primarily as a vehicle for sharing its research and findings with a community of shared interest. The research collective responsible for operating and maintaining the IUH opened it for public tours every Saturday afternoon from 1 to 5pm.

Word of the attraction travelled fast, and tours were often packed by an appreciative audience of families, students, and seniors. On the weekdays, the house could be booked for private tours by schools and other organizations. A self-guided tour booklet by Helga Olkowski gave homesteading tips and further references. (A short video ‘tour’ can be watched here.) As a pedagogical tool, these tours not only oriented visitors to the IUH, but also provided them with the knowledge needed to replicate the resource-saving design features in their own homes.

Word of the attraction travelled fast, and tours were often packed by an appreciative audience of families, students, and seniors. On the weekdays, the house could be booked for private tours by schools and other organizations. A self-guided tour booklet by Helga Olkowski gave homesteading tips and further references. (A short video ‘tour’ can be watched here.) As a pedagogical tool, these tours not only oriented visitors to the IUH, but also provided them with the knowledge needed to replicate the resource-saving design features in their own homes.

The Integral Urban House also sponsored a variety of classes to teach grassroots ecology and its practices. Topics ranged from beekeeping and organic pest management to how to build a D.I.Y. solar water heater. For urban residents with little to no experience in these areas, classes provided a supportive environment in which to learn these new skills. Compared to more conventional models of lecture-based education, the IUH promoted a hands-on model of pedagogy: a “learning by doing” method that was enormously successful, and which, through its fees, helped fund operating costs.

A Trojan House: Appearances Can Be Deceiving

When visitors arrived at the Integral Urban House, they were greeted by the pleasant façade of a quaint, late-19th century Victorian house. A light peach-colored coating of paint provided homespun charm; white trim and accents conveyed the look of a clean, well-kept home. Yet a step inside revealed interior spaces vastly different in organization and function than suggested by the street front view.

Le Corbusier, the 20th century modernist architect, made famous the phrase: “A house is a machine to live in.” Focusing their attention on energy flows and biological systems, the architects affiliated with the Farallones Institute might have framed the dictum as “A house is a living machine.” Indeed, the Integral Urban House was conceived the way an engineer might, starting from inputs including energy flows, water use and circulation paths, and life support systems. Photos of the facility in operation show Institute members teaching participants how to work with materials to create the “living machine” of the house, as seen with this woodworking demonstration.

A wood-carving demonstration-workshop at the IUH

Unlike the architectural machine aesthetic embraced by orthodox modernists, however, the Integral Urban House packed its carefully calibrated mechanisms for ecological sustainability within a nostalgic Victorian wrapper. The design choice was strategic, rather than the byproduct of its adaptive reuse of salvaged building stock. As opposed to the cool, industrial feel of a purpose built lab building, the homey qualities of the Integral Urban House “living laboratory” allowed visitors to feel familiar and at home with a dwelling that demanded a radical recalibration of domestic habits and a lifestyle profoundly alien to the labor-saving ethos of postwar American consumerism.

A photo series, shot for a Time/Life publication, highlights the communalism inherited from back-to-the-land agrarians and redirected toward urban ecological research. Farallones Institute members and volunteers helped with daily tasks like growing and harvesting vegetables, feeding rabbits and chickens, or irrigating the garden with greywater reserves. These activities bonded a community of like-minded individuals interested in environmental conservation and the reinvention of urban environments as sites of ecological custodianship. At the end of the day, they could take home the fruits of their labor!

The Integral Urban House remained in operation for over a decade – a respectable lifespan for a grassroots experiment in alternative living. The endeavor was not without shortcomings, however. As time wore on, the IUH confronted multiple operational problems and eventually had to close.

The Final Years of the Integral Urban House

In the late-1970s and early-’80s, the Integral Urban House no longer attracted sufficient public attention to supply volunteer labor or generate operating funds from visitor tours and classes. Countless hours of construction and management were supplied by unpaid architecture students, a situation that ultimately proved unsustainable. The Farallones Rural Center, an even larger and more complex project initiated by the Institute in western Sonoma County, further reduced the funds and administrative effort demanded by the IUH.

Sim Van der Ryn’s relocation to Sacramento to establish the state’s Office of Appropriate Technology, the world’s first government agency devoted to sustainability investment and policy, further reduced IUH access to the University and its pool of volunteer student labor. As financial and human resources dwindled, the Integral Urban House spiraled toward dissolution.

Architectural historian Sabrina Richard posits that the IUH project also dissolved due to its social disengagement from local citizens. Whole Systems Design, she maintains, failed to take into account the changing “political economy of the environment, and as such was unable to respond to many dynamic, external conditions.” By the early 1980s, city-initiated redevelopment efforts around Berkeley’s Fourth Street brought an influx of young homebuyers to the area. Smells and noises generated by homesteading activities at the IUH created friction with new, affluent neighbors and were incompatible with the investment culture of gentrification.

Despite efforts by Farallones Institute members, insurmountable differences emerged that led to their project’s demise. Stripped of its ad hoc, first-generation solar equipment and sold as a starter home in yet another marginal but up-and-coming neighborhood, the shell of the former “living laboratory” still exudes its Victorian charm.

The Living Legacy of the Integral Urban House

Does the dissolution of the Integral Urban House mean that the experiment was a failure? By a financial definition of success, based upon growing profits as a business reaches maturity, the answer would be yes. But other notions of success are more appropriate for a project that was intended to explore a radical re-fashioning of modern domesticity, alternatives to ecologically degrading consumer lifestyles, and a novel ethos of environmental custodianship.

If the ambition of the Farallones Institute in creating the Integral Urban House was to generate and circulate knowledge, provide experiences unavailable elsewhere, consolidate activist networks, and generate new individual and social possibilities, the project was a success. The Integral Urban House project itself may have faded out of sight, but its legacy continues to be felt.

Appointed in 1975 by Governor Jerry Brown as the first California State Architect, Sim Van der Ryn raised building energy standards and created the state’s first modern office building to depend completely on solar heating and cooling. His work with the Office of Appropriate Technology laid the groundwork for California to become a global leader in sustainable, climate-conscious design.

Back in Berkeley, the Farallones Institute applied what had been learned in the IUH project to propose plans for an Integral Urban Neighborhood. As the name implies, it expanded the features of the Integral Urban House to include community gardens and a collective waste management system with features like a methane digester to produce methane gas for energy production at a larger scale. While it was never built, this pioneering project began to devise strategies for the urban repair and neighborhood-scale reinvestment approaches favored by progressive urban planners today.

Meanwhile the most practical ambition of the Integral Urban House — to popularize urban agriculture and to engage residents in actively producing their own food and controlling their energy use — has been taken up today by urban farming projects across the East Bay. Through production and distribution of fresh organic food and produce, they reduce reliance on industrialized agricultural and corporate retailers, address the problem of urban “food deserts,” and empower local communities. Whole Systems Design, while notably transformed from its expression in the Integral Urban House, has continued to evolve and adapt to changing social and economic conditions.

– Wesley Tam

Wesley Tam (Cal ’21) is a fourth-year student, double majoring in Geography & Conservation and Resource Studies. He is intrigued by the production of urban space, particularly as it relates to identity and the natural environment.

Wesley Tam (Cal ’21) is a fourth-year student, double majoring in Geography & Conservation and Resource Studies. He is intrigued by the production of urban space, particularly as it relates to identity and the natural environment.

Acknowledgments

Thank you so much to Professors Scott Saul and Greg Castillo for creating this course and leading us through an important time in our history.

Thank you to Jim Campe, for use of his photos and documents through Professor Greg Castillo. Thank you to Andie Thrams for her illustrations and information about the Greenhouse project in Berkeley. They were invaluable sources of information on the portrayal of the Integral Urban House and Berkeley in the ’70s.

Sources referenced

Owen Gump, “Outlaw Builders: Film Screening & re-release of the 1972 Publication Outlaw Building News,” Anne T. Kent California Room Community Newsletter.

Helga Olkowski, Self-Guided Tour to the Integral Urban House (Berkeley: Farallones Institute, 1973).

Untitled, Integral Urban House, Berkeley [Photograph]. (Anne T. Kent California Room, Marin County Free Library, San Rafael, 1975).

“The ultimate city garden: Californians create a small farm on a tiny urban plot,” Time-Life Gardening Yearbook (1978), 83-92.

Sabrina Richard, “Integral Urban House,” Critical Sustainabilities. Published 1 June 2015, accessed 1 May 2020.

Sim Van der Ryn, Design for Living: The Architecture of Sim Van der Ryn (Layton, Utah: Gibbs Smith, 2005).

Additional reading

Sim Van der Ryn, “Abstract of Proposal to Build an Ecotectural House,” unpublished, November 1972.

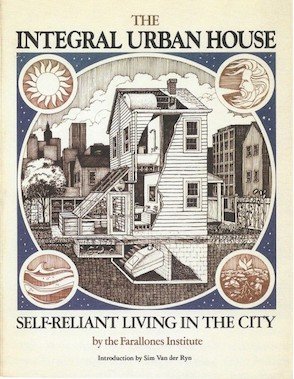

Farallones Institute. The Integral Urban House: Self-Reliant Living in the City. (San Francisco: Sierra Club Books, 1979.)

Julie Reynolds, “Urban Homesteading: The Integral Urban House,” Mother Earth News, November 1976. Accessed 23 April 2020.

The Integral Urban House served as a prototype for a revolution in urban-ecological design and living