Citizens vs. Developers

Berkeley is a city that takes pride in its “firsts,” so it’s fitting that the current shape of the city has been deeply shaped by a first in the realm of city planning: 1973’s Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance (NPO), which applied restrictions on large-scale redevelopment efforts and was the first law of its kind in the country.

The NPO was conceived as a response to “urban renewal”—the development policies, built upon partnerships between city governments and private developers, which often involved the razing of older neighborhoods and which critics attacked for their displacement of longtime residents and for their homogenizing of the urban landscape. A number of citizens of Berkeley watched, with trepidation, the redevelopment of San Francisco and the construction of Bay Area Rapid Transit. They treasured their own city’s charm — its natural setting between the sparkling bay and green hills; its neighborhoods shaped by the Arts and Crafts movement —and wondered what would happen when the bulldozers came to Berkeley.

After developers unveiled a plan to expand the industrial portion of West Berkeley, threatening a historic neighborhood, these residents sprung into action. The results of their organizing included the Landmarks Preservation Ordinance, which protected structures of cultural significance, and the more radical NPO, which applied protections to all residential structures.

The story of the NPO is one of community watchdogs standing up to business interests in the name of progressive preservation, a story of citizens stirring a debate about what makes a neighborhood worth protecting. Yet the NPO has not achieved everything that its organizers hoped. While the Berkeley landscape has, by and large, avoided the effects of large-scale redevelopment, the density restrictions have also contributed to a shortage of housing relative to demand. Meanwhile at least one of the NPO’s goals — the construction of more low-income housing stock — has proved especially elusive.

Berkeley’s Historic Architecture

The home of John Maybeck, cousin of Bernard, at 1423 Grove St.: an early instance of the brown-shingle style (courtesy William M. Maybeck)

Much of Berkeley’s architecture reflects a woodsy utopianism. At the turn of the century, architect Bernard Maybeck brought to the city a fresh style through his iconic brown shingle houses, whose unfinished redwood tiling and exposed rafters evoked a cabin-like coziness. The use of native materials and simple, homey designs inspired the likes of Julia Morgan and William Wurster, and many vernacular structures came to emulate these architects’ styles.

Berkeley became known for its range of beautiful homes, from the estates in the hills that complemented the natural landscape to the humble but well-built bungalows in the flats, many of them bursting with gardens. By 1916, Berkeley’s idyllic neighborhoods were so beloved that the city became one of the first in America to establish a city planning commission and enforce zoning regulations. (Wollenberg 2008)

West Berkeley Industrial Park: A Proposal to Expand Industry’s Footprint in the City

In the aftermath of the East Bay’s production boom during World War II, planners wanted to expand the industrial zone of Berkeley outward from the narrow sliver West of Fourth Street. In the 1950s, with the adoption of the original Master Plan of Berkeley, an adjacent area between Camelia Street and Dwight Way was declared a mixed-use “Special Industrial Zone.”

In the 1960s Republican Mayor Wallace Johnson and the Berkeley Chamber of Commerce went one step further with their proposal to create West Berkeley Industrial Park — a plan that would raze eight blocks of houses (displacing over 200 people from 66 dwellings) and sell the land to industry at subsidized rates. The City Council handed the project over to the Berkeley Redevelopment Agency, a bureau it had created largely to insulate itself from the blowback they expected after the noisy and public failure of the South Campus Urban Renewal Project. (For more, see David Mundstock’s history of Berkeley politics in the 1970s.)

Background to the Fight for the NPO: the Berkeley Tenants Union and People’s Park

Civic activists were determined to fight the Berkeley Redevelopment Agency (BRA), whom they viewed as mercenaries for shady developers in the battle between commercialism and people-centered design. They came to this battle with a sense of local history, and with a sense of larger battles over development. As they observed, African-American neighborhoods like the Fillmore in San Francisco had often been the first to be targeted for demolition. The construction of freeways and BART stations, in the 1960s and 1970s, had rendered some neighborhoods unrecognizable.

Even as high-rise buildings shot up, so did rents — giving birth, in Berkeley, to a newly mobilized tenant rights movement. Rent strikes in Berkeley protested unlivable conditions, and groups like the Berkeley Tenants Union and the Fair Rent Committee advocated a vigorous commitment to rent control. Those protesting the exploitation of renters were convinced that Berkeley needed more housing, so the West Berkeley plan to demolish residential units for industry brought them together with homeowners.

As with much of Berkeley’s history in the 1970s, the battle over People’s Park was a crucial prelude to this later skirmish. People’s Park had pitted Berkeley political activists against the forces of development: citizens had occupied a vacant lot owned by the university, turning it into a public park to create a space for greenery and free speech activities. The participants highlighted the need for public open spaces and for community involvement in opposing powerful interests like the university. The establishment of the park convinced organizers that they could win such struggles even when the government, the law, and money were not on their side; the intense and often ugly presence of law enforcement — from local police to the Alameda County Sheriff’s deputies to the National Guard — had often worked to bring the protest community together.

Ultimately, the battle over People’s Park energized local activists to pursue city beautification as a political end — to make “a thousand parks bloom.” It set the stage for a radical approach to neighborhood preservation and maintenance.

Activists Respond and Organize: the Ocean View Committee

Once the Berkeley Redevelopment Agency received its federal funding and began buying up houses, people from the targeted blocks and the surrounding area launched the Ocean View Committee. Reviving a historic name for West Berkeley, the committee’s goal was to restrict the WBIP project to West of Fourth Street, which had been zoned for industry all along; much of that area had remained undeveloped.

The Ocean View Committee leveled numerous complaints against the City Council, HUD, and the BRA board, and organized protest actions to dramatize their resistance to the development plan. When the first five houses were demolished in February of 1971, dozens of protesters met the bulldozers; a man had to be forcibly dragged out of a house before it was torn down, and several people were arrested for trespassing, all of whom were spared reprisal for their civil disobedience by hung juries.

The WBIP was a city-wide issue because many residents saw it as the proverbial canary in the coal mine — the battle that would determine whether the city bowed to the forces of development or resisted them. Two insurgent forces in city politics, the April Coalition and Berkeley Citizens Action, formed an alliance with the Ocean View Committee. With the City Council stalled at numerous 4-4 votes on changing the plan, organizers teamed up with opponents to the Yerba Buena Redevelopment Project in San Francisco to file a federal lawsuit, which resulted in requiring an Environmental Impact Statement. The EIS delayed the BRA until 1974, by which time the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance had been passed. (Lewis 2016)

Working Toward the NPO: The Vision of Martha Nicoloff and Kenneth Hughes

Beginning in 1972, a group of Berkeley citizens organized out of a shared sense of their alarm at the large apartment buildings that were supplanting older houses in the campus area. They called these apartment complexes “ticky-tacky” — meaning shoddily made and ugly — and saw them as jarring with the charm of Berkeley’s craftsman and Edwardian homes.

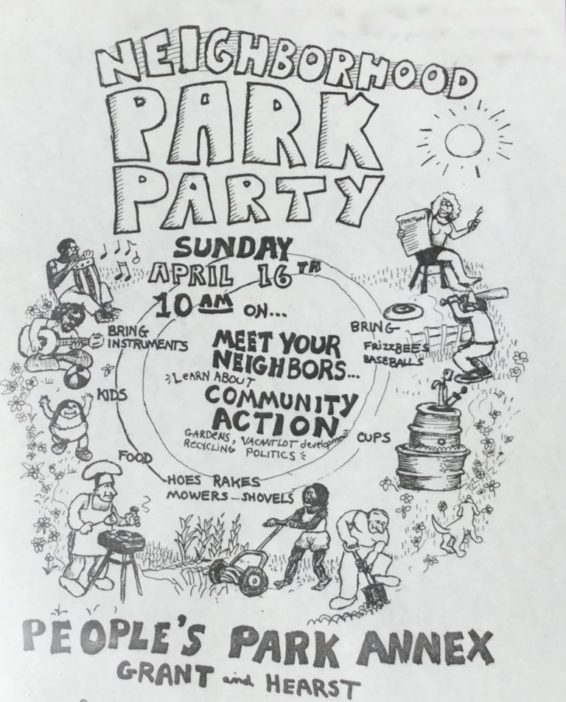

“Bring instruments, kids, food, hoes, rakes, mowers” and “learn about community action”: Martha Nicoloff’s flyer for a neighborhood park party

The two primary organizers behind the movement were Martha Nicoloff and Ken Hughes. Nicoloff had moved from the crowded tenements of Chicago to the Berkeley flatlands, where she fell in love with the feel of the neighborhood, with its small homes. An arts teacher, she became Chair of the North Berkeley Neighborhood Council and organized toward the creation of Ohlone Park—then called People’s Park Annex. (She had had a hand in the battle over People’s Park, where she was struck by a policeman’s baton.) She was involved in the Ocean View neighborhood and opposed the rapid construction of tall, shoddy buildings — a phenomenon that was taking neighbors by surprise and led to the idea for protection of all structures, not just historical landmarks.

Hughes, a recent graduate in economics from UC Berkeley, had founded “People’s Legal Services” — a legal aid organization specializing in tenant’s and welfare rights — and was interested in opposing runaway development.

Nicoloff teamed up with Hughes to form the Berkeley Housing Council and held “People’s Housing Conferences” to bring together rent control advocates, preservationists, and concerned students. The idea for the ordinance had originally come from neighborhood organization in Ocean View, but activists saw the need to cover the whole city in order to bring a wide base of support. The ordinance would down-zone wealthy neighborhoods in the hills in addition to protecting the flatlands from speedy development.

They started drafting a land use ordinance — one which began by establishing a tight restriction on housing demolition and a permit requirement for new housing, then was expanded to include a mandatory revision of the Master Plan and a requirement for multi-unit buildings to reserve units for low to moderate income tenants, called inclusionary zoning. The restriction on demolition included a mandate for public hearings of the Board of Adjustments before a permit could be issued — an attempt to give neighborhood oversight to the city’s plans.

After the proposal was rejected 6-1 by the City Council in late 1972, organizers took to another strategy: the initiative process, which would allow them to bypass the City Council and go straight to the public. Volunteers gathered enough signatures to put the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance on the ballot for April 1973.

Passing the NPO: The City Election of 1973

No opposing arguments on the NPO were submitted to the Voters’ Handbook until March 13 when the City Council itself proposed going on record against the NPO, but it was past the legal deadline. Berkeley’s Chamber of Commerce took it upon itself to mail an official-looking pamphlet of ballot arguments against the NPO and several other measures. The publisher of the Berkeley Gazette came out against the initiative, warning that when radicals turned to the ballot, it was “much more dangerous than [when they were] on the streets.”

The efforts by the City Council, Chamber of Commerce, and Berkeley Gazette were ineffective: the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance (“Measure 2”) passed with 59% of the votes, 27,280 to 18,698.

The election as a whole, however, administered a few blows to the bloc which had supported the NPO. The conservative slate beat out the April Coalition for three out of four City Council seats, and a set of more radical initiatives — initiatives for police residency in Berkeley, police weapons control, public ownership of PG&E, and a law to lower the working week to 30 hours without changing pay—failed. Meanwhile a clutch of progressive reforms, such as the Berkeley Marijuana Initiative, Mutual Aid Pact Regulation, and Police Review Commission, passed.

In retrospect, it was the ordinance’s ability to unite homeowners in the foothills with flatland renters that pushed it to victory. When NPO co-author Ken Hughes analyzed the election results, he offered that the most affluent residents of Berkeley, who lived up in the hills, had “managed to entrench themselves in low density levels and thus have no need for revisions.” The triumph of the NPO, he suggested, was a triumph of the people from “non-hills Berkeley” who had helped to draft it, and were pushing back against the “suburbanization of Berkeley” wished for by developers and its most affluent residents.

Immediate and Longterm Legacies of the NPO

The NPO immediately became a tool in the battle against the West Berkeley Industrial Park. The Berkeley Redevelopment Agency was snarled up with judicial injunctions every time they tried to demolish a house, and eventually the city was ready to sell a large portion of the park to an industrial laundry business called ARA Services Inc. The deal did not go through, in large part due to a Berkeley Barb article that exposed the company’s history of bribing public officials and links to the mafia. A newly composed City Council, elected in 1979, put the kibosh on the project once and for all.

Energy around neighborhood preservation gave rise to the Berkeley Architectural Heritage Association, which continues to work in landmark preservation. The NPO also resulted in a 1977 Master Plan which lasted over 20 years, one which featured low-density residential zoning and avenues for citizen participation.

The trend started by the ordinance has kept Berkeley environmentally beautiful, relatively un-congested, and architecturally unique, but it has contributed to a shortage of housing and exorbitant rent prices. People certainly want a degree of control over how their neighborhood is shaped, but such efforts can have unintended consequences or can meet up against new obstacles.

Take the issue of low-income housing: in 1978, five years after the passage of the NPO, both its supporters and detractors noted that, despite its requirement that one out of four new apartments be reserved for low-income housing, there had been no significant rise in low-income housing stock. In fact, low-income housing stock had not increased at all since the NPO’s passage — a trend that NPO co-author Ken Hughes chalked up to a national slowing of new construction, but that others traced to the NPO.

The 2017 price tag of this 1BR/1BA home in Ocean View: $800K

Or take the issue of the current affordable housing crisis in Berkeley. This modest, attractive 650-square-foot home in the Ocean View neighborhood of West Berkeley was preserved through the efforts of activists like Nicoloff and Hughes, and through the workings of the NPO. The selling price of this one-bedroom one-bath home, in late-2017, was $800,000.

The history of the Neighborhood Preservation Ordinance in Berkeley suggests that determined citizens can sometimes overcome powerful political interests and create a world of new possibilities, but that a “perfect victory” is very hard to achieve.

— Seamus Kirkpatrick

Further Reading

Elliot Lewis, “The West Berkeley Industrial Park Redevelopment Project,” FoundSF. 2016. Accessed April 29, 2018.

David Mundstock, “A History of Progressive Electoral Politics,” Berkeley in the 70s. Accessed April 28, 2018.

Charles Wollenberg, Berkeley: A City in History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008).

A money-hungry kitty-bulldozer pounces on the city of Berkeley: the vision of development from a pro-NPO flier