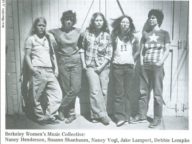

Berkeley Women’s Music Collective

“Every breath was a challenge. Every day was a challenge. Finding every note was a challenge. Driving every mile was a challenge.”

— Suzanne Shanbaum

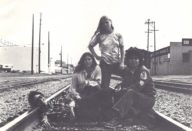

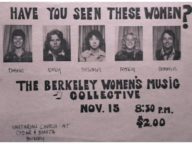

When Debbie Lempke posted a flier at the Berkeley Co-op around 1973, inviting women to play music together, she didn’t know how thoroughly her flier would change four lives. Although none of the participants realized it at the time, the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective held its first meeting the following week.

Members of the Collective, all lesbian feminists, soon began writing songs about the personal experience and shared struggle of finding freedom from patriarchy. With the women’s liberation movement in full swing, a passionate audience was ready and waiting.

The music of sisterhood spread its demands for equity across the country, bringing like-minded women together to celebrate at festivals and concerts. Within this newfound community, women experienced acceptance, freedom from societal expectations, and new ways to express gender and sexuality. A novel genre of popular music, made by and for feminists, encouraged women to change the way they lived their life.

For the members of the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective, the band provided an opportunity to have their voices heard at a revolutionary moment that changed the politics of gender and sexuality in America.

Setting the Stage: The Historical Context of the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective

Many women growing up in the fifties found themselves at a crossroads. They felt the angst of mothers who had been driven out of the workforce after World War Two and witnessed their relegation to traditional homemaker roles. Yet at the same time, women growing up as white baby boomers were told that they had the keys to the kingdom in an expanding economy of mass consumer affluence.

During the 1960s, young women “who had grown up with that privilege of thinking that we had the keys… realized that the keys were not on our ring. They were on [those of] our brothers, our uncles,” as Nancy Vogl, the Collective’s rhythm guitarist, recalls. Debbie Lempke, the band’s drummer, remembers growing up wanting to become a veterinarian: “I wrote a letter to Cornell University and I was like, well, what should I do to prepare and what would you recommend? And they wrote me back, “Females are not accepted into the veterinary program.” Just as real as their generation’s privileges were the ways in which a patriarchal system constrained choices and opportunities.

Then came the counterculture. Electrically amplified music and day-glo colors suddenly made the Kodacolor world of sprawling suburbs and Betty Crocker kitchens seem drab by comparison. Baby boomers were coming of age and revolution was in the air. “Everyone who’d been playing guitar in their bedroom or writing in their bedroom or had been taking photos in their bedroom or had been struggling with not fitting in in everybody’s bedroom all over the country came to Berkeley in 1970,” remembers Suzanne Shanbaum, the Collective’s bassist. As young people hungry for change flocked to the Bay Area, its community of political and social activists reached critical mass.

Of all the recruits converging upon the region’s counterculture scene, the most important for the Music Collective were the lesbians and feminists settling in neighborhoods along the Berkeley/Oakland border. The area became the focal point of a new geographic imaginary extending from Bay Area feminist communities to the rural lesbian communes established on the “Womyn’s Lands” of southern Oregon.

Across this realm, women reexamined selfhood and reinvented relationships, language, and culture. Amazon Quarterly, a D.I.Y. journal published by Gina Covina and Laurel Galena from their home basement in Oakand, emerged as the vibrant national conduit of a lesbian feminist literary culture. In another basement, this one beneath A Woman’s Place bookstore in North Oakland, the Women’s Press Collective published a fresh generation of feminist voices. It was among these women, who were in the process of finding themselves and devising a culture liberated from patriarchal oppression, that the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective found its initial audience.

Finding Berkeley, Founding the Collective

The women who would form the Music Collective followed a variety of paths that brought them to Berkeley. After traveling abroad, Nancy Vogl knew that going back to her hometown wasn’t an option. When she visited a friend who had moved to Berkeley, she decided it was the place for her. Suzanne Shanbaum transferred from Northridge to UC Berkeley. Although she didn’t think the university was a good fit for her, she knew that that town was. Debbie Lempke was enrolled at Reed University in Portland when women’s liberation swept her into the movement. Deciding that it wasn’t the time to be in school, she soon found herself in Berkeley.

Lempke and Shanbaum met a party held by a local lesbian feminist commune, where they traded turns singing songs. Lempke then met Nancy Henderson, the Collective’s piano player, on third base at a women’s softball game. Henderson lived in a communal household with Nancy Vogl. Upon hearing her playing guitar in her bedroom, Henderson invited Vogl to join the group.

The Mission: Intersections with the Women’s Liberation Movement

The timing of the band’s creation proved crucial. Women’s liberation politics were glowing hot and the musicians wanted their voices heard. “I found the band was crucial, the timing was crucial,” Lempke recalls. “I was very, very aware that I was in this historical period. I wanted to get out there right away. And so I think we got together and right away we were arranging and we’d do our songs.” Each member of the Collective had a story about arriving at this point in her life, and those stories had to be shared.

As the women’s liberation movement blossomed, it wanted music that spoke to their experiences. Folk and protest music had achieved mainstream success in the ‘Sixties through the songs of Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, Joan Baez, and Joni Mitchell. “When the ‘womyn’s music’ era is jeered at today, we forget that nearly all women and men in every society grow up with access to heteronormative songs and lyrics from cradle onward,” observes Bonnie Morris, a women’s studies professor at Georgetown and George Washington University. “Lesbian musicians scrambled to write songs for every possible narrative of a lesbian’s life—girlhood, adolescence, coming out, coupledom, breakup, partner loss, discrimination.” Pushed to the margins as untouchables by popular music, lesbians now demanded a music of their own.

The Berkeley Women’s Music Collective gave their audience what it had longed for. Band members wrote songs that celebrated their own experiences, and thousands of other women related to them. The personal connection listeners felt towards the band’s lyrics and harmonies inspired the women of the Collective to keep making music. The symbiotic relationship between artist and audience happening throughout a new feminist culture was shaping modern lesbian identity. Women who had been made to feel out of place their entire lives suddenly found acceptance and celebration.

The sea change in how lesbians experienced selfhood permeated the Collective’s music. Having grown up as a misfit, Lempke still remembers the struggle to remain true to who she was: “I was a tomboy, big into sports and in the ‘Fifties it wasn’t okay. It was like there’s something wrong with you; you have to go into therapy, where they basically take gay people and they try to make them straight. But I had learned to rally for myself.”

“And I just felt like, I’m okay, what’s wrong with them? Why won’t they just let me be myself? So I did go through that for three years in elementary school, and I got into a big dilemma about should I just pretend like I’m more feminine to get out of this situation where I have to go in every week and I was afraid if I did that, then I would kind of lose my identity; that I would forget who I was.”

In providing alternatives to straight-jacketed gender roles, the Women’s Movement saved women’s lives. Women-only spaces provided a safe zone of acceptance and showed feminists and lesbians that their community could show up in force to fill a room. For many women, attending women’s music festivals and concerts provided the only opportunity to fully express themselves and experience deep acceptance. In their travel to gigs across the United States, the members of the Berkley Women’s Music Collective were radical “cultural workers,” taking responsibility for embodying liberated notions of gender and sexuality across the nation.

Vogl has never forgotten the impact that impact women’s music had on its audience: “Women in Little Rock, Arkansas, who were just dying out there and ready to commit suicide, knew that one week a year they could go and be with a tribe, people where they belonged. And it saved women’s lives. There’s no doubt about it at all.”

“You said, why did we play music? We knew that women were offing themselves or drinking too much or doing drugs because they couldn’t come out. Cause wherever they were, they couldn’t be fully human and express their full humanity. And so a part of our work was to go from town to town to let other women know that it was possible.”

“I’m not trying to be self aggrandizing that we were any big shakes, but I’m just saying by our mere existence we provided an alternative to self-medication and an alternative to self harm and there were a shit ton of women who were stuck in that dynamic.”

The Music: Influences and the Women’s Music Community

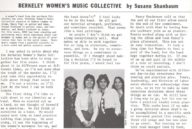

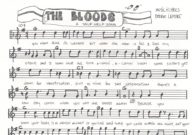

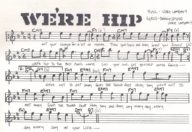

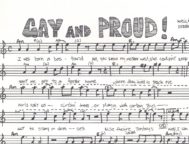

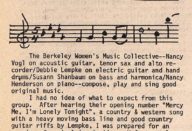

During the six years they were together, the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective released two albums. The band’s self-titled debut was released in 1976. The group’s sophomore album, Tryin’ To Survive, came out in 1978. Both albums can be listened to on this site.

Stylistically, the band’s music spanned multiple genres, including folk, blues, jazz, country, and gospel; this range reflected the wide spectrum of music that had shaped them, often from an early age. Shanbaum listened to jazz and doo wop, which translated into the arrangement of the band’s harmonies. Lempke grew up hearing music associated with Jewish culture; Henderson played gospel hymns in her church. Vogl listened to country-western; with parents in the theater, she was raised on musicals. All the women listened to folk. Only Henderson was classically trained. (During their time in the band, Shanbaum and Lempke both enrolled at the Berklee College of Music in Boston). The absence of a shared musical language originally made it difficult for the band to communicate, but the passion they had for music drove them to overcome this challenge.

The songs of the Collective drew upon these various genres, but translated them into the songwriting of the late-’60s, in which personal storytelling played a strong role. All members of the Collective were inspired by Laura Nyro’s songwriting — especially how she powerfully centered her own feelings and experiences, even if that meant abandoning the more conventional songwriting form of verses and choruses.

Historically, women were relegated to minor roles in the music industry, which limited female musicians to acoustic instruments and folk songs. The new women’s music community offered the alternative of a non-judgmental environment created by and for women in which to hone their craft. It provided female musicians with an escape from competition with men and access to encouraging listeners who understood their music and struggles.

However, even the women’s music crowd preferred solo-artists and sentimental songs. Vogl recalls the frustration that this caused among Collective band members: “We were a little too outside for even feminism, because Meg Christian, Holly Near, Margie Adam and Cris, women just wanted to fall in love with them. They were middle-class. They were non-offensive. They were singing about love songs for the most part and women could just go and kind of fall in love with them.”

Although bands were a rarity in the women’s music community, the Collective and other all-female bands of the period—the Chicago and New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Bands, Clinch Mountain Backsteppers, Bebe K’Roche, and the New Harmony Sisterhood Band—showed feminist audiences the pleasures of an ensemble format traditionally associated with male musicians.

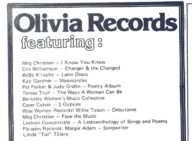

Success did not come without its challenges. After struggling to find a label that would produce them, the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective recorded both of their albums independently. For most female musicians, securing a studio recording presented one of the most difficult barriers to attaining equal status with their male counterparts. Both of the Collective’s albums were distributed by Olivia Records, a prominent women-owned-and-operated label that demonstrated the feasibility of independence from the male-dominated music industry.

The End: Assessing the BWMC Legacy

The women’s music movement revolutionized American models of gender and sexuality. Through songs about their struggles with patriarchy and oppression, members of the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective created a harmonious experience of liberation that could be shared with appreciative audiences.

Singing a lesbian feminist culture into existence did not come without hardship, however. Women’s concerts and productions were ad hoc, D.I.Y. affairs: few women had been afforded the opportunity to professional skills as producers, engineers, lighting and sound technicians, managers, or indeed even musicians. As a result, the Collective learned to do everything for itself. “Every breath was a challenge,” Shanbaum remembers forty years later. “Every day was a challenge. Finding every note was a challenge. Driving every mile was a challenge. I mean everything was a challenge. There was no not [a] challenge.”

Although the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective never became a household name, it advanced a movement that changed thousands of women’s lives and planted the seeds for future generations to cultivate. As Vogl reminisces about the Collective’s dispersal, she speculates that successes in promoting greater gender equity eroded the band’s revolutionary edge and niche audience: “I think the real seed of radical cultural change pushes the envelope a lot. All of us as young radical feminists were the only ones in our family who felt the way we did. But then each of us had nephews and cousins and parents and brothers and sisters, and so the thousands and thousands of women who were being impacted by feminism and radical feminism were influencing the young men who were growing up.”

“And so women were rearing boys who were different than their fathers. So I could say that a part of our success, and maybe one of the reasons that we died out, is that the dominant culture started integrating some of the concepts and the theories that allowed me to exist in it. You didn’t need to go to a women’s concert because then you could go see Melissa Etheridge, you could see Joan Armatrading.”

The Collective may have dissolved more than four decades ago, but the ideals it stood for continue to be relevant today. The Me Too movement showed that the issues the band sang about have yet to be resolved. However, the pioneering role of the women’s music movement as a force for social change has yet to be recognized, as Vogl observes: “Without an acknowledgement of the seed of where the popular commercial women musicians came from, you don’t know that we ever existed. It’s like the Rolling Stones. They were responsible for finally giving credit to the black musicians in the South who play blues.”

“And in the same way I think that’s a little about us…. I think what you’re doing is showing the roots of what has emerged as the Me Too movement because this is what we were saying 40 years ago: ‘Stop it, that’s inexcusable.’ It took 40 years, but this is what we were talking about back then. It was just too soon.”

— Lily Ramus

Lily Ramus (Cal ’23) is a rising second year student majoring in music. She is interested in musicology and hopes to work on more projects like this one.

Lily Ramus (Cal ’23) is a rising second year student majoring in music. She is interested in musicology and hopes to work on more projects like this one.

A Few Notes

During her time in the band, Suzanne Shanbaum spelled her first name “Susann”.

Throughout this project quotes from interviews have been edited for length and clarity.

Acknowledgements

I would like to extend the warmest thank you to Debbie Lempke, Suzanne Shanbaum, and Nancy Vogl for their enthusiasm, interest, and contributions to this project. Thank you for sharing your rich history and amazing stories, I hope I have helped eternalize some of them on this site. I would also like to thank professors Scott Saul and Greg Castillo for their support throughout this project. Throughout this semester I have learned so much about the rich history of rebellion in the East Bay. Finally, to all the women, feminists, and lesbians who were part of this movement: Thank you for your fight.

References and Additional Resources

Interview with Suzanne Shanbaum, conducted by Lily Ramus, transcript edited by Suzanne Shanbaum, April 11, 2020.

Interview with Debbie Lempke, conducted by Lily Ramus, April 24, 2020.

Interview with Nancy Vogl, conducted by Lily Ramus, transcript edited by Nancy Vogl, April 13, 2020.

Bonnie Morris, “Olivia Records: The Production of a Movement,” Journal of Lesbian Studies. Jun. 15, 2015.

Bonnie Morris, “How Should We Archive the Soundtrack to 1970’s Feminism?,” Smithsonian Magazine, Mar. 30, 2018. https://www.smithsonianmag.com/arts-culture/how-should-we-archive-soundtrack-1970s-feminism-180968637/

Judith Periano, “Homomusical Communities,” Listening to the Sirens (University of California Press, 2005), 152-194.

Sarah Dougher, “Sex and Laughter in Women’s Music, 1970-77,” Current Musicology, Fall 2010, 35-56.

There is a great digital archive of Olivia Records, with a wonderful page on the Berkeley Women’s Music Collective.

The Pacifica Radio archive has some great audio clips of the Collective performing, available here.

Suzanne Shanbaum performs "Fury" with other members of the Berkeley Women's Music Collective (1975)

A playlist featuring the Berkeley Women's Music Collective's first, self-titled album (1976)